“Shh... Philae is fast asleep.”

Philippa Skett recaps the Rosetta mission and the future of Philae

It’s the space mission that has had both scientists and members of the wider public waiting with baited breath. The Rosetta mission has been a nail-biter of a ride since the awakening of the craft back in January, and has left news rooms and control rooms alike buzzing all through summer as the craft approached its final destination that it’s taken ten years to reach.

Beginning its journey in March 2004, Rosetta launched from French Guinea and took to the skies, skating around the planets of the Solar System and finally dropping into a deep sleep to conserve energy in 2011. Named after the Rosetta Stone, the archaeological relic that allowed for deciphering of the hieroglyphics, scientists hoped that the spacecraft would help unravel the mysteries surrounding comet composition, and discover more about the origins and evolutions of the solar system.

Rosetta targeted 67P, a comet that completes an orbit of the sun every 6.45 years and rotates every 12.4 hours through its axis. Shaped like a roughly hewn dung bell, it has two rotund protrusions that extend away from each other and is roughly 4km wide and long at its widest points. Samples taken from the comet show that it might actually have been two separate comets at one point that have fused together, as each protrusion has its own separate core.

Rosetta reawakened back in January, much to the anticipation of the team back at home and the rest of the world waiting eagerly for news from the spacecraft. When the signals were sent back to the European Space Agency after several hours of agonising wait, the world erupted in excitement, although it still seemed that the odds were against this tiny craft flying millions of miles away in space.

At the time, scientists were still staying realistic and weren’t ruling out failure just yet. Said Paolo Ferri, the head of missions operations at ESA: “There is a possibility that we’re not going to hear anything. Two-and-a-half years are a long time. We’re talking about sophisticated electronics and mechanics. We’ve taken all possible precautions for this not to happen but of course we cannot exclude that problems may have happened.”

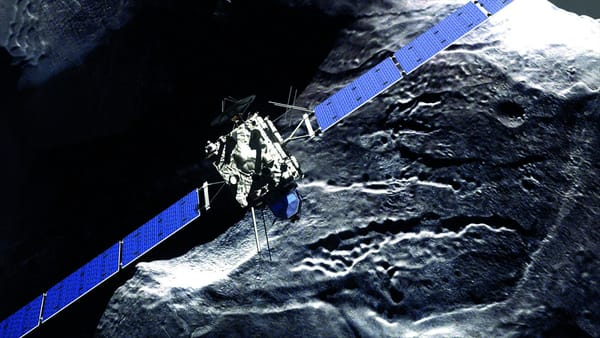

Fortunately, everything went smoothly from the hibernation reawakening onwards. Rosetta was able to approach the comet, descend close to its surface, then finally deploy its landing probe, known as Philae. Around the size of a fridge, Philae boasts sampling and recording equipment, including a drill to take samples from the surface and a camera to take photos.

The only hitch occurred when Philae bounced upon impact when dropped onto the comet. Philae bounced twice across the surface of the space rock, and then came to rest at an angle, with solar panels hidden from the sun. It is thought that the surface of the comet was so dense that the hooks of Philae were unable to anchor it sufficiently enough to prevent it moving further.

Despite sunlight hitting the panels for only 90 minutes every 12 hours, all 10 of the instruments on board managed to collect data. Temperatures were taken, photos were captured and a small sample was taken from the surface of the comet and analysed.

Philae struggled on for 64 hours before its batteries gave out, and it now lies dormant, riding the comet around the solar system as it approaches the sun. The team back at ESA have managed to reposition the probe so that one of its solar panels is facing upwards and has the potential to be reactivated once closer to the sun. It may come alive once more and send further information back to earth, but already the mission is considered a major success.

The final message from the official Philae Twitter account simply said: “I’ll tell you more about my new home, comet 67P soon ... zzzzz.”

But why hunt down comets? As they have been flying around since the start of the solar system, they are almost like flying time capsules; they usually haven’t changed in 4.6 billion years. They sweep up molecules in their dusty atmospheres and hold onto them as they spin around the solar system, forming a cosmological scrapbook of all the debris that has been flying around space since the birth of the solar system.

Latest news from ESA confirms that Philae has detected organic molecules on the surface of 67P, which are now being analysed to see how complex they are. Although Rosetta has already detected ammonia, methane, methanol and even formaldehyde in the coma – the gases that surround the comet – the dream was to discover amino acids, the building blocks of proteins and all lifeforms on Earth.

Said Dr Matt Taylor, one of ESA’s Rosetta project scientists: “the data collected by Philae and Rosetta is set to make this mission a game-changer in cometary science.”

Rosetta will continue to follow the comet as it approaches the sun, so the story doesn’t end here. Rosetta will approach the surface of the comet itself in the future, which might give us another opportunity to learn any other secrets 67P may be hiding. For now, all we do is wait.