“Everyone thought it was a bit of a crazy idea.”

Chris Carr talks to James Bezer on his role in the Rosetta expedition and just how hard it is to do science in space

How did you get involved with Rosetta?

That goes back a long time. I was first involved in 1997. Our group is interested in space physics, making measurments of plasmas, particles and magnetic fields. At the time I was working on Cluster — a project to map the earth’s magnetic field. When the ESA was looking into Rosetta, they wanted a team to run the magnetometer, and they came to us because of our experience on Cluster.

My Principal Investigator, Andre Balogh, got involved and came together with other groups to develop the instrumentation package, with Imperial as the main data processing centre. I later became the lead at Imperial.

What is Rosetta trying to achieve that couldn’t be done by telescopes or previous spacecraft?

Rosetta isn’t the first mission to a comet — there have been quite a few. The most famous is the Giotto mission to Halley in 1986, but there were two others in the same year: a Russian and a Japanese mission, which were looking at the comet as it was close to the sun, boiling off lots of gas and dust and making a big spectacle. They flew through this cloud, the coma of the comet, at about 10km/s, in just a few hours.

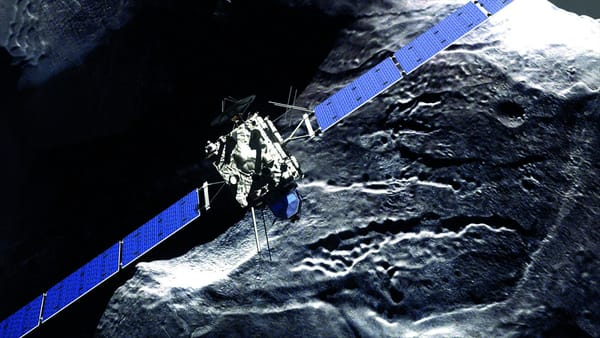

What Rosetta is doing is fundamentally different. It’s no longer a fly-by mission as it’s in the same orbit as the comet and will travel with it, observing its evolution over a whole year as it boils off dust and gas. We needed 10 years to get there as we had to get gravity assists from Mars and Jupiter in order to match the speed of the comet.

Rosetta will also be making in situ measurements of its chemical composition. You can’t use instrumentation on earth if you want to sample what the comet is made of and investigate the dust and gas coming off it.

Your group works on the magnetometers on the Rosetta orbiter. What are you trying to find out with this instrument?

We’ve been involved with magnetometers on other space missions, particularly Cluster and Venus Express, and will be building the magnetometer for Solar Orbiter, the BepiColombo mission to Mercury, and the JUICE mission to Jupiter.

The magnetometer on Rosetta was built in Germany. What we built is the ‘brain’ and the power supply for the whole consortium that connects the 5 plasma sensors. There’s also a separate magnetometer on the lander, Philae, run by a different group.

We don’t know much about the magnetic field around a comet, although it won’t be very strong. You have a magnetic field from the sun and solar wind, which drown out any signal you’d get from the comet.

When the comet starts boiling off lots of dust and water molecules, the particles coming off get ionised by UV radiation from the sun. This creates lots of highly conductive plasma around the comet, which shield off the solar wind. This should let us see how the comet’s magnetosphere develops. We hope to compare these magnetic field measurements with those from the lander to see what this can tell us about the nucleus.

Have you discovered anything interesting so far?

We’ve seen two things that we weren’t expecting.

Water molecules boil off the comet and are ionised by solar UV radiation. These ions should gyrate and produce a magnetic field with a characteristic frequency. We’ve seen a frequency much lower than we expected — about 30-50mHz. This doesn’t really fit with our understanding of how ionised water molecules should behave.

As well as that, we’ve seen low energy water ions coming directly from the comet at thermal speeds, as expected. We’ve also seen some at much higher energy. We think they have actually drifted past the spacecraft and been pushed back by the solar wind — they can achieve higher energies because they’ve had longer to be accelerated.

How do you operate a spacecraft so far away from earth?

In principle it’s run like any other mission. Emanuele Cupido is responsible for communicating between our group and the ESA.

We have a set of protocols to send command instructions that are prepared in advance. This is necessary not only because it has to be carefully checked, but also because you don’t have real-time access. There is a half-hour delay in communication because of the distances involved, and the limit imposed by the speed of light.

From our perspective it’s not much different to other missions. From the ESA’s perspective though, it’s very different because it’s a deep space mission, about 500 million kilometres away. You can only communicate using extremely large antennae, which requires dedicated facilities. The ESA’s are in Australia, but we also share NASA’s Deep Space Network.

What challenges are there in operating an instrument for Rosetta compared to something in a lab on earth, or on a satellite in orbit around the earth?

The earth orbit environment is usually worse. In deep space, we mostly have the constant radiation from the solar wind, but we also need to deal with occasional solar flares and very high energy cosmic rays. On Cluster, a satellite that studies the earth’s magnetic field, we have to deal with all that plus the extra radiation from the van Allen belts of charged particles.

The temperature is extremely low, and that’s a challenge, but the radiation environment isn’t too bad.

What will be a big challenge is the dust and gas.

We usually think of a spacecraft in a vacuum. In this case, the comet will boil off gas and dust from below the surface. The real challenge for Rosetta is that this will collect on the orbiter and create drag. Usually Newton’s laws will tell you exactly where a spacecraft will be, but this extra drag makes Rosetta’s motion unpredictable.

How do you go about designing an instrument to send into deep space?

If we want to measure particles or a magnetic field, the instrument technology is pretty well developed. Particle detectors for use in the lab are relatively easy things to make.

If we want to send an instrument into space, we’re trying to measure extremely small magnetic fields and plasma densities (about 1-2 nanotesla (compared with 40-50 on earth), so we need very sensitive instruments. They have to be very high quality, but also very robust to survive the rocket launch and extreme cold.

The key thing though is reliability. Almost uniquely for a piece of instrumentation, we can’t just go up and fix it if something goes wrong. We use a lot of military-grade electronic components with guaranteed reliability and radiation hardness. This also makes things very expensive — for Rosetta, each chip costs around $10,000. And to ensure reliability, there’s a lot of redundancy built in so if one fails we always have a back up.

What have you been doing for the past 10 years while Rosetta was travelling to the comet?

It hasn’t been entirely dormant whilst we’ve been flying there. There was some data to be taken while we were flying past Earth, Mars and two asteroids. All instruments were operational in those periods, being tested and helping us prepare for the rendezvous.

At Imperial, we’ve also been heavily involved in programmes like Cassini and Cluster. Rosetta was a part-time project, but it’s suddenly become very busy.

How closely have you been working with other groups?

The plasma consortium is a big team already, with people involved from right across Europe and the US. We do work with other teams though, particularly the magnetometer on the lander, so we can compare our measurements with them. There’s also a mass spectrometer, and an instrument on the orbiter called ROSINA, which investigates neutral gases and ions. There are big meetings with all three groups — the next one’s in three weeks — where we share our findings and see how measurements from different instruments can support each other.

Has the mission gone as you expected when you first started working on the project?

Actually it has really. The goal of Rosetta was to make the first rendezvous with a comet, characterise it in orbit and send the lander down, and we achieved that.

Everyone thought it was a bit of a crazy idea. To rendezvous would be hard, to land would be even harder. NASA’s Comet Rendezvous was cancelled because of the difficulties involved, but the ESA persevered. Across the project there’s been a feeling that it was hard but we did it.

What else are groups at Imperial working on at the moment?

I’m the principal investigator (PI) for the magnetometer on Cluster, which keeps me occupied most of the time. I also run the Space Magnetometer Lab here. Groups from Imperial are working on planned missions: BepeColombo to Mercury and Solar Orbiter — the PI for that magnetometer is Tim Horbury. We’ve recently been selected to build instruments for the JUICE mission to Jupiter that Michele Dougherty will be working on — a lot of the development for that will be done at Imperial.

We’re also working on CubeSats: miniature satellites to map the magnetosphere using sensors similar to those you find as compasses in phones. They aim to relate the magnetic field in low-earth with that measured by an array of ground-based detectors to see how the solar wind penetrates the earth’s magnetic field.