Guerilla Girls: The Male Gaze

Fred Fyles selects a powerful work from W. Eugene Smith

In 1984, the Museum of Modern Art in New York opened a new exhibition: ‘An International Survey of Recent Painting and Sculpture’. it promised to be a survey of the most important artists currently working in the art world. Not everyone was impressed. Out of the 169 works featured, only 13 were by women artists, a fact that was not helped by the curator, Kynaston McShine, saying that any artist not in the show should rethink his career. In 1985, one year after the show opened, the Guerrilla Girls were formed by seven women artists. And the rest, as they say, is history.

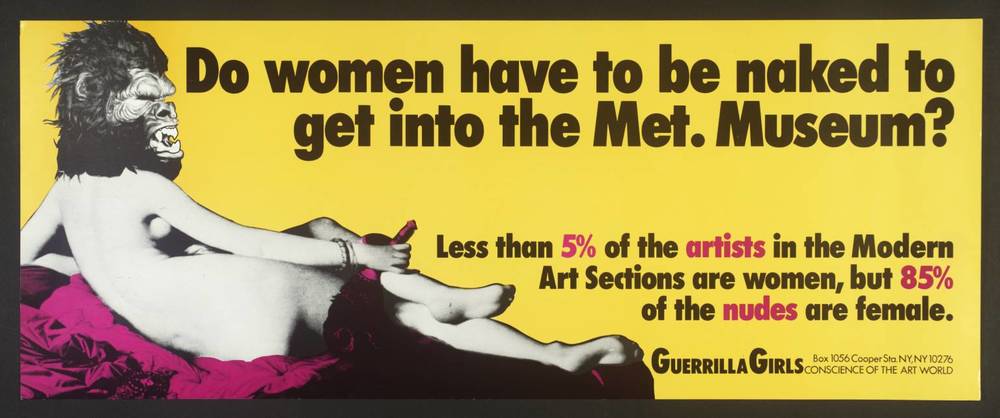

Their most famous work is immediately arresting; on a yellow background, bold black text screams: “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met Museum? Less than 5% of the artists in the Modern Art Sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female”. Offset with an image of Ingres’ painting La Grande Odalisque, where the woman’s head has been replaced with a gorilla, their statement is immediately clear; women are under-represented in art galleries, except where they are the subject of the Male Gaze.

The Male Gaze was coined by feminist film-theorist Laura Mulvey, who saw it as a power structure between the sexes; with heterosexual men in control of the palette, the camera, the chisel, many works of art became little more than a means of titillating the man in power. In effect, most works of art put us in the perspective of a straight man, making the woman a sexual object. This is apparent throughout all of art history; one only needs to go and look at the key painters of yore, and their key themes; for Rubens, Titian, Velazquez, the female nude was a near-obsession.

Since Mulvey, this idea has taken on a life of its own. John Berger, writing in Ways of Seeing, says that it infiltrates how men and women appear in society: “Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at”. In art, the woman is always aware of being the subject of the Male Gaze, and in Renaissance painting, would often be portrayed staring into a mirror, admiring herself as an object of adoration.

While the Male Gaze may be the most famous example of the phenomenon of the ‘Gaze’, it is by no means the only form. It can be traced back to French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan, who defined it as the state that comes with awareness that one is an object to be viewed. From this somewhat nebulous definition, more and more academic disciplines have sprung up.

We have Foucault’s Medical Gaze, where the patient becomes ‘a mere text through which disease can be read’; there is the Colonial Gaze, which describes how the privileged majority place that which is ‘foreign’ into the category of Other; and there is even the Female Gaze, which shows such as True Blood could be seen to use.

When those seven artist friends got together in 1985, they probably had little idea how much they would shock the art world. Taking on the names of dead women artists such as Käthe Kollwitz, they set out to challenge the status quo of the day. While things have gotten better, they still aren’t perfect: women are still underrepresented in the arts, both in the market and the gallery. The work of the Guerrilla Girls thus continues, and will carry on until the Male Gaze has been replaced with a much more even sight.