Art History From A New Perspective

Aleksandra Berditchevskaia goes behind the scenes at the all new View Art Festival

I recently came across an opinion piece in Art Review magazine that discussed the crisis of the contemporary within art, particularly focussing on the difficulty in finding a suitable label for the art of the present day. With ‘modern’ art confined to a temporality at the beginning of the 20th century, and the use of both ‘postmodern’ and ‘contemporary’ rapidly falling out of favour, a new word is being called for. The author drew attention to the increased use of the term ‘now’, which has seemingly been employed to resolve this problem. At first glance, the organisers of View Art Festival at the Institut Français, were not faced with confronting this dilemma. After all, their ambitious programme, which took place over the weekend linking February and March, was concerned with discussions around the topic of art history.

The variety of events on offer ensured that there would be something to suit anyone with a mild interest in the arts, even if that something was merely fulfilling a desire to rub shoulders with the continental art crowd. There were free short talks running throughout the day on Saturday, complemented by debates of a longer form to lead on from the challenge posed by the Friday night opening discussion on ‘Redefining the Artistic Canon’. The billing featured contributions from many respected curators, art historians and other representatives of the French and British art establishment. My favourite elements of the programme related to the Preserving and Restoring focus, with questions such as ‘How do preservation and restoration of art works determine the course of art history?’ under discussion by the best minds in the field.

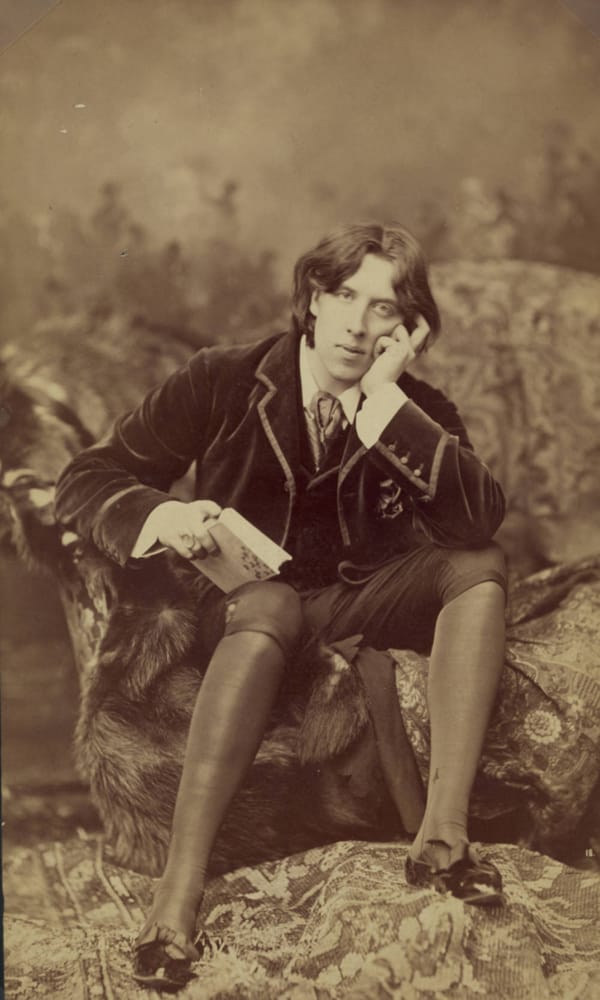

Delaunay cultivated her own version of what it meant to be an artist in the modern world

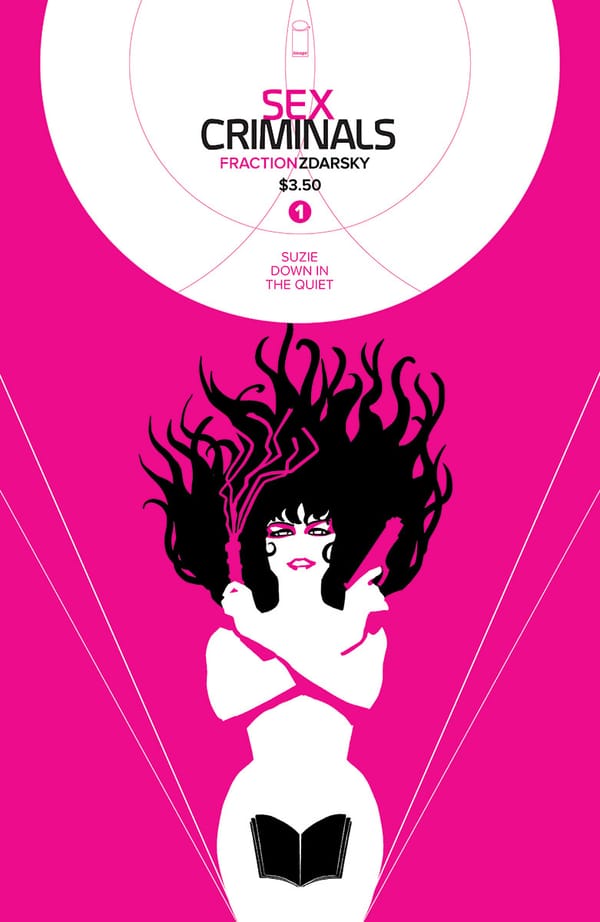

The concurrently running series of student-led ‘salons’ with intriguing titles along the lines of ‘The Tales of the Killer Rabbit’, on the other hand, ensured that a fresh perspective on art theory from the next generation of critics was also voiced. For a public less partial to the topics of conservation and collections, the ‘Avant-Gardes and Precursors’ strand also had plenty to offer. The star draws were probably the Saturday night appearance of the inimitable Jeremy Deller, winner of the 2004 Turner Prize and Britain’s representative at the 2013 Venice Biennale, and a screening of the Dadaist film Entre’acte on Sunday afternoon.

Anyone who managed to attend the ‘My Night with Philosophers’ event hosted by the same organisation two years ago would be able to understand my nervous anticipation of the queues I was likely to encounter, especially in view of the quality of the programme. However, on entering the main building of the French cultural centre early on Saturday afternoon I was surprised to find the staff to visitor ratio peculiarly balanced to oppose my expectations, and the atmosphere surprisingly subdued.

She represented a stark contrast to the Russians who were motivated by Socialist ideology.

I was there to attend a fascinating insight into the Tate’s upcoming Sonia Delaunay retrospective, delivered by the curators of the Parisian rendering of the exhibition. The Institut Français provided a particularly appropriate setting for this discussion about Delaunay and her ideology – one of her colourful abstract tapestries normally hangs above the main staircase of the entrance hall.

Constrained by a short-talk format, the speakers provided a regrettably brief overview of the work and life of this doyenne of modern art. A key figure of the European avant-garde, she defied easy categorisation. Despite engaging with the numerous emergent movements of the first half of the twentieth century, including particular intimacy with the Parisian members of Dada, Sonia and her husband Robert remained at a distance and cultivated their own version of what it meant to be an artist in the modern world. Delaunay’s understanding of this transcended the boundaries of aesthetic art and allowed her to engage with fashion, interior design, traditional craft, theatre and film as media for delivering her message. She often modelled her own designs at social events, almost suggesting an early version of performance art. For Sonia Delaunay a line between art and life was unnecessary; all of her activities and collaborations bled into and complemented each other, continually drawing attention to her other work. The curators argued that this warm embrace of self-advertising coupled to an interest in the industrialisation of design processes reflected a utopic vision which had capitalism at its core. In this way, she represented a stark contrast to the similar developments amongst her Russian contemporaries, the Constructivists and Suprematists, who were motivated by socialist ideology. The talk was supported by images of the exhibition, which along with the persuasive rhetoric of the speakers helped to generate a genuine excitement for the opening of this show in April. Apart from paintings, the exhibition is set to feature tapestries, photographs, costumes, furniture and books – a feast for the senses drawn from the richness of the oeuvre of this remarkable artist.

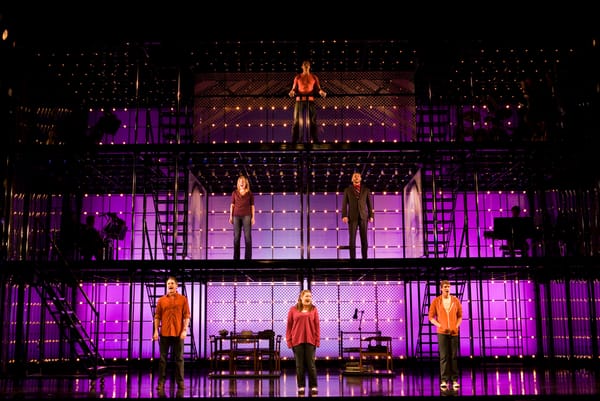

In contrast to the talks, the guided tour listings seemed to be the more popular events of the Festival, with all of the options selling out well in advance of the opening night. I was lucky enough to reserve a place on a ‘Behind the Scenes’ visit to Blythe House, which is home to the archive collections of the British Museum, V&A and Science Museum. The tour description promised items that had never been on public display, which, coupled with 15 person cap on participants, helped to instil a sense of excitement from the outset.

The almost palatial grandeur of the Grade II-listed Blythe House tucked behind the Kensington Olympia exhibition hall, seemed a world removed from the bustle of the Hammersmith Road that led me to it. Its illustrious history, the source of numerous anecdotes from our vivacious hostess Rebecca, was enough to satisfy most of our appetites for an exclusive experience even before we made it through the foyer to start viewing the collection. Blythe House holds 85% of the objects owned by the Science Museum, with only “anything larger than a washing machine” being allocated to a more spacious storage site in Wroughton. Overall, this means that the public galleries on Exhibition Road hold only a tiny proportion of the curiosities that the museum has to offer. Our guides around the treasure trove were two dedicated members of the collections and curatorial team, whose unlimited enthusiasm and background knowledge ensured that we were entertained throughout.

Perhaps to remain relevant, art history needs to find its own version of “now”.

We worked our way through the different levels of the building, descending from the top floor storage aptly dedicated to Space and Aviation to the ground floor rooms housing the, often bizarre, peculiarities collected by Sir Henry Wellcome of the Wellcome Trust. This medically-themed part of the tour included an entire room of wooden prostheses, while another was filled with statuettes of saints associated with wellbeing and ancient sacrificial objects intended to promote health and fertility.

Many of the objects in the collection hold a purely aesthetic beauty and I don’t doubt that anyone interested in the history of modern design would relish a visit to those rooms. Whether your passion lies with telescopes, planes, ships, or the history of medicine or the development of modern technology such as telephones and audio speakers, there is much to take your breath away. Our whistle-stop (two-hour!) tour concluded with a visit to the conservation studio where museum staff were busy cleaning old calculators in time for their appearance at a new exhibition dedicated to Mathematics. The presence of a Biosafety Hood and the strong smell of chemicals in the room almost brought to mind a typical lab space at Imperial!

Whether your passion lies with telescopes, planes or medicine, there is much to take your breath away.

It felt incredibly special to be allowed to freely wander around those rooms and inspect the objects; I can’t help but echo the sentiments of Sir Roy Strong, a former director of the V&A, who argued that the site “should be not just a dumping ground but an exciting new complex for the public” when the original bids for the space were first being put together. I guess that, until an increase in arts funding makes that possible, we must place our faith in the curators of the Science Museum exhibitions as they select which of those items should be brought out of hiding to best tell the inspiring stories of science.

Considering my own overwhelmingly positive experiences at the festival, I can’t help but think how much of a shame it was that the event did not attract more attention. Did the programme not pack enough of a punch? Or is it more likely that organisers of an art history festival (even if one of the themes deals with the subversive avant-garde) will always be faced with the burden of shedding the stuffiness and highbrow scholasticism that is associated with the term? Perhaps to remain relevant and interesting to a new generation of art lovers, art history needs to engage with the wider debate of the art world and find its own version of ‘now’. I just hope that View Festival survives another year in order to lead the way.

The View Festival was on at the Institut Français, 27th Feb - 1st March.