Et in Arcadia Ego, Unfortunately

Jack Steadman is less than entranced by Stoppard’s classic drama

A disclaimer, before this review goes any further. I have extraordinarily strong feelings and opinions about Arcadia. I studied the text for A-Level, and directed the show for DramSoc in the summer of my first year of university. It’s been a huge part of my life for the past few years, and it’s only fair to the English Touring Theatre production that I make that plain before passing comment on their show.

Originally appearing in 1993, Arcadia is easily Tom Stoppard’s most popular play, if not one of English literature’s most popular plays – a claim acknowledged in the programme notes for this latest large-scale production, where it is revealed that it came near the top of their audience poll of future play ideas. It’s an exquisitely composed work set entirely in the large drawing room of a country house, with scenes transitioning between 1809 and 1993.

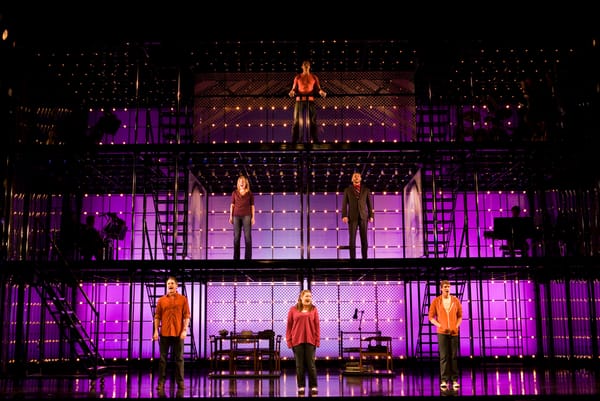

This single-set approach is usually a cue for the set designer to go overboard with extravagant designs for the room and all its furniture, and on first glance this production appears to be no exception. A vast wall occupies the upper third of the stage, with enormous windows looking out onto the gardens of Sidley Park, home to the aristocratic Coverly family. The room is large, and the expansive table squatting in the centre of the room does little to cover the swathes of empty space surrounding it – but that’s fine. The room’s emptiness is explained away by the script at one stage, and as the play progresses the table (and by extension the room) rapidly becomes more cluttered and disorganised, echoing one of the key themes of the play. Unfortunately, no excuse is given for what lies on the other side of the aforementioned large windows. The gardens are revealed to simply be the rear wall of the stage, in all its undisguised glory. No painted backdrop, not even a black tab. A grey wall, replete with cabling and sockets. Whatever the reason for this particular set choice, it’s not exactly the most auspicious start to proceedings, considering that the house opens with the set (and the wall beyond it) clearly visible to the entire audience.

Much of the comedy is lost, leaving the script to fight for itself

So far, so unimpressive. But having heard the director Blanche McIntyre speak about the play, expressing her love for its complexity and how she and the cast spent hours unpacking all of the science behind it to ensure they could fully convey the themes to the audience, I’ve got a lot of goodwill sitting in the tank, so I’ll let it slide.

Sadly, the first two scenes rather quickly threaten to squander every last drop of that goodwill. There are some positive moments – the scene change is nicely handled, with the characters from past and present crossing paths with each other on stage, drawing attention to the similarities between the two eras. Some of the cast members are simply stellar in their performances. Others, less so.

Flora Montgomery deserves particular praise as Hannah Jarvis. In a role created by (and written for) Felicity Kendal, she makes it her own, perfectly capturing Hannah’s blend of external Classicism and internal Romanticism. In the past scenes, Kirsty Besterman makes an impact as Lady Croom. The role is a treat for any actress, providing ample opportunity to dominate the stage, and Besterman runs riot with it, taking full advantage of Croom’s unwavering control of the scene. It’s just a pity that neither actress really gets decent sparring competition – at least not to begin with.

There’s a weird sense of lethargy permeating the opening scenes, starting with an oddly subdued Dakota Blue Richards as Thomasina, the prodigal daughter of the house, and spreading from there. At times, it’s only the sheer joy of the script that saves proceedings, with the jokes themselves, if not their delivery, prompting occasional outbursts of laughter. There is some defence for this, in that while the later scenes do a lot of the heavy lifting for explaining (relatively) complicated scientific or mathematical principles, the early scenes have to do a lot of the groundwork for making those ideas make sense in the context of the play as well as – obviously – introducing all the key players.

But that defence doesn’t really stand up when an early confrontation, traditionally the part where the play springs to life after a lengthy dialogue between Thomasina and her tutor Septimus, fails to ignite. Much of the comedy is lost, leaving the script to fight for itself. To its eternal credit, it succeeds, proving the theory that it’s impossible to make a bad show out of Arcadia. It’s just possible to do Arcadia badly.

Another scene change later, and I’m starting to have second thoughts about this production. Is it just my personal bias, the intrinsic “this is how Arcadia should be done” that comes from directing it, or is something genuinely off with this show? One glorious moment of physical comedy a second later, however, and suddenly I’m sold. Everyone seems to wake up, and everything speeds up enough to revive the play’s flagging momentum. Nakay Kpaka’s Ezra Chater, the would-be poet, finally becomes the incompetent, flouncing comic relief he’s supposed to be. Faced with a livelier companion than the subdued Thomasina, Wilf Scolding’s Septimus comes alive, revelling in the Byronesque wit of his character. Even the 1993 scene that follows feels livelier, with Ria Zmitrowicz’s effervescent Chloe Coverly standing in stark contrast to her counterpart from the past.

When the case settles, the majority hit the notes just right, although a wonky feeling remains

This recovery continues unimpeded by the interval, making for a far more competent second act, and meaning the play feels like a much stronger production overall than the early moments would suggest. When the cast settles, the majority find their roles and hit the notes just right, although there are enough miscast roles to unbalance the show and leave a distinctly wonky feeling. But touring a show is always hard on any cast, and hopefully with a few more performances (in front of some very different audiences) the whole cast will find their feet and be able to hit the ground running every night.

This production of Arcadia, then, is very much a mixed bag. Gorgeous yet un-intrusive lighting design, minimalist (arguably to the point of detriment) set design and adequate sound design combine with a masterful script and various calibres of performance to produce something ultimately watchable, and enjoyable, albeit with some almost unbearable low points. It’s the embodiment of ‘hit and miss’, and at no point is this more obvious than in the very last moments. The play’s soaring emotional crescendo, as Thomasina and Septimus waltz in the past to the strains of modern-day music, is played perfectly and strikes exactly the right tone – only to be undone by the appearance of the other characters in the background, looking on. It’s an artistic decision that feels slightly off, and undermines such an intimate moment that was done so well. It’s a huge shame, as the bum note of the final moments can’t help but taint the good work that came before. This isn’t a bad production of Arcadia. It’s just not a very exciting one.