It All Could Have Been So Beautiful

Joshua Jacobs is let down at the National Theatre’s new production

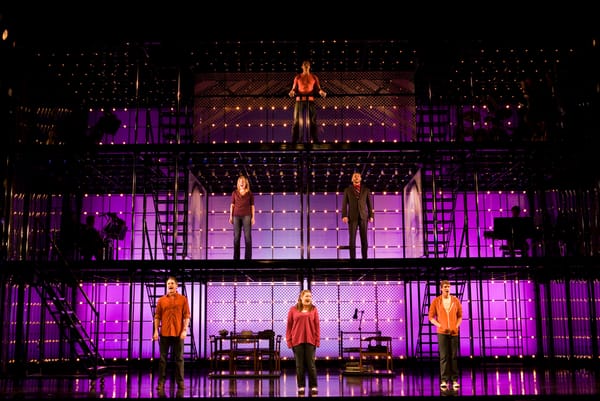

Behind the Beautiful Forevers, based on the nonfiction book by Katherine Boo, and adapted for the stage by David Hare, is currently on at the National Theatre. Hare’s adaptation is principally mediocre, and does very little but leave me wanting. Set in a slum outside the Mumbai airport, the play begins with a stage littered with refuse, waiting to be collected, along with a backdrop of crude temporary buildings. Shane Zaz’s character of Abdul Husain is anchored at centre stage sorting rubbish, whilst other young characters run around collecting what they can, thus clearing the stage. This scene foreshadowed the tone of the first half of the play, not only in that it shows the frenzied nature of the characters’ lives, but also the insincerity of the production, which extends to the whole play. Booming electronic Indian music attempts to corroborate and justify the pace of this scene, as the characters frantically run to and fro across the stage. However, the balance of the music forcefully reminds the audience that they are in a theatre, and that the characters moving around on stage are performing for them, undermining any possible immersion into the world in which this play is set.

I doubted the legitimacy of the characters because of the confused subtext

At points I doubted the legitimacy of the characters; this was not due to the actors ability, but instead because of a confused subtext. The characters’ behaviour was not validated by what they were saying, and instead I felt like there was a collection of ideas and context that filtered down from the original book, via the playwright and director – some of them were coherent, some were now confused, and others weren’t present at all. If you are going to adapt a book, and cannot recreate it without losing some of the content, we need to consider whether the play can stand alone apart from the text. It is important that references and behaviours which become spurious in the script and production are removed, otherwise the play loses it’s integrity and becomes confused, as this play did – allusions were made to internationalisation and the effect it has on local communities, tolerance of different religions, and disabilities in India, but they were trivialised by the illegitimacy of what else was going on stage.

This is a major shame, as such issues are current and highlight why the book was successful. The comedy within the play was inelegant and childish, and thus distracted further from any serious political discussions that occurred on stage. If this was an employment of Brechtian practices - something I doubt - it only served to make the experience less enjoyable, and it was done in vain. Not only was there no distinctive discussion, but the audience were again overly aware of being in a theatre.

Norris’ direction and Hare’s adaptation failed the book, the cast, and the audience

The staging was ambitious: early on in the play, masses of rubbish fall from above the stage, to cover it yet again, as it was in the first scene; in the closing scene a character performs a jump from scaffolding, to highlight the risks that the characters made to earn money; and the most exceptional part of the whole production was when lights and sound flew a plane over the audiences heads. Although the latter device was exciting and by no means mediocre, it only served as a counterpoint to the rest of the play, and each event just seemed like an attempt to wow the audience. Although they were fun to watch, it felt disjointed from the bulk of the play. Further to the plane flying over the audience, the lighting was particularly clever, and effective at creating different spaces on a large open stage.

The set, which at points was deconstructed and reconstructed, was mostly based on a large turntable, meaning the characters could walk from one scene to the next without leaving the audience’s sight. Aside from the turntable, it felt gimmicky and - like the majority of things in the play - still couldn’t distract from the flimsy script. I feel that Rufus Norris’ direction and David Hare’s adaptation failed the book, the cast, and the audience, resulting in a staging that could do little but distract the audience from the aforementioned failures – this play is an excellent example of artistry not correlating with size of budget. I don’t, however, doubt the brilliance of the book, and I would love to see another adaptation of it, as I am sure the stage could be an effective medium through which to discuss the topics involved and for telling such a story. Rufus Norris is the incoming Director of the National Theatre; I hope this is an anomaly in his work, and the bathos pervading this play does not extend to his further work at the theatre.

_Behind The Beautiful Forevers is on at the National Theatre’s Olivier Theatre, until May 5th. _

_Tickets from £15. _