Antigone: An Atonal, Atypical Astonishment

Juliette Binoche impresses Fred Fyles, in this measured, unique production of Sophocles' Antigone

In a recent interview, given to promote his 2014 production of Arthur Miller’s A View from the Bridge, which opened at the Young Vic to overwhelming critical acclaim before making the switch to broadway, Belgian director Ivo van Hove said ‘I am not so interested in good and evil’. Therefore, it seems that he is an incongruous choice for director of Sophocles’ Antigone, a classic that so clearly revolves around ideas of ‘right’ and ‘wrong’. This fact, combined with the reputation van Hove has obtained for his radical reinterpretations of the stalwarts of the theatrical canon, means that those attending the Barbican’s production of Antigone – somewhat of a misnomer; this is in fact an international production, with input from French, British, Luxembourgian, and Dutch companies – are already expecting something out of the ordinary.

Combine this with the fact that the lead role is being taken on by French actor Juliette Binoche, a legend of arthouse cinema who has starred in films by Jean-Luc Godard, Krzysztof Kieslowski, and Michael Haneke, and the hype surrounding the production reaches fever pitch. Of course, this is only the latest in what seems to be a new trend of established actors taking on some of Greek theatre’s most challenging women; after Kristin Scott Thomas’ turn in the Old Vic’s Electra, and Helen MccRory’s interpretation of woman scorned in the National Theatre’s Medea, it seems that Binoche has a lot to live up to. Luckily, this production of Antigone does not disappoint, although the effect of van Hove’s direction is disconcerting; it hits all the right notes, but plays an atonal tune.

Antigone hits all the right notes, but plays an atonal tune

It is Canadian playwright Anne Carson who has taken on the challenge of translating the original Greek text, updating it for a more modern audience. A high drama, Antigone centres around the daughter of Oedipus; cursed by birthright, with a family ‘double triple degraded and dirty in every direction’, Antigone has had a life of misery and shame – her mother’s granddaughter, her father’s brother, Antigone has seen her two brothers kill each other in battle over control of the city-state of Thebes. The void left has been filled by her uncle Kreon, who attempts to establish some kind of order in the war-torn city through autocratic rule. His first edict: to bury Eteocles, the defender of Thebes, and to leave Polyneikes, who launched the war, out in the desert, unburied and unmourned. Defying her uncle, headstrong Antigone buries the body, and is therefore condemned to death.

At first sight this seems to be a straight-cut tale of a tyrant opposed to humanity, but Carson’s translation helps reintroduce the ambiguity at the heart of the play – the interaction between physis, or natural laws, and nomos, those laws made by man. Antigone bluntly refuses to acknowledge these new laws – ‘you call that law...Zeus does not/Justice does not’. Binoche says these lines, not with venom, but with a simple clarity – consigned to her fate, all she can do is shrug her shoulders. And yet, Antigone is far from a sympathetic figure; as unrelenting as Kreon, she goes towards her death like a reckless teen. When her sister Ismene (Kirsty Bushell) tries to share the responsibility for the burial, Antigone screams at her ‘leave my death alone/you did not lay a hand on this/you cannot make it yours/for me to die is altogether adequate’, to which Ismene can only reply ‘I’ll be so lonely’. Antigone also seems to exhibit Freud’s Death Drive, as she rushes headlong into the abyss; fantasising about her coming doom, she envisions the tomb as a bridal chamber where she shall ‘marry’ her brother – ‘one day we’ll lie together in the grave he and I side by side/for death is long’. Antigone is above all a complex character, exhibiting both a challengingly unendearing nature and an understandable motive for her actions; Binoche excels, with a measured, nuanced performance.

A particular highlight of the translation is the skill with which Carson has handled the stichomythia, or alternating single lines. As Antigone argues with Kreon, the rhythm of these lines help create an atmosphere of high tension, driving forward the drama; not only that, but they give a chance for Antigone, that ideal of a headstrong heroine, to show her cutting wit: ‘one man rule has its advantages doesn’t it’ she says; ‘you’re the only person in Thebes who sees things this way’, he replies; ‘no actually they all do/but you’ve nailed their tongues to the floor’. Such well measured, economical verse is a highlight in what is an excellent interpretation of the original text, something for which Carson should be applauded.

For those audience members expecting emotional crescendos and pummeling pathos, prepare to be let down. van Hove makes the radical decision to have the characters speak their lines in calm, even tones; it robs the text of its urgency, but somehow works, conjuring up an atmosphere of unease reflecting the moral quandary at the heart of the play. It is as if someone has sucked the oxygen out of the room, leaving behind a vacuum that can only be filled with our undivided attention. Patrick O’Kane is especially good in the role of Kreon, imbuing his tyrant-king with insecurity and a coldness that only breaks towards the end of the play, when his actions have brought about the destruction of his clan. I believe that had van Hove made the decision to play Antigone straight it would have become just another in a long line of Greek tragedies, or – worse – a hammy melodrama.

It is as if someone has sucked the oxygen out of the room, leaving a vacuum that can only be filled with our attention

What also sets this production apart is the lack of that most characteristic of features: a chorus. Instead of having the traditional group of elderly Greek men, van Hove lets each actor in turn take on some of the lines spoken, resulting in a democratic version of Antigone, in which one character blurs into another. The effect is startling, and it is only when reading the script that one realises who is supposed to be saying what. This decision, to split up what is traditionally seen as some form of conscious, reflects the insecurity that lies at the heart of all of the characters.

That being said, there are some moments of the play that simply don’t work: the lines of the guard, for example, are delivered in such a way as to try and conjure up a humour that just doesn’t sit right within the production; the fact that the actors’ voices are so levelled means that many have to be mic’d up, which completely alters the quality of sound, and means that the rustling of clothing is amplified to an annoying degree. The effect of such things is to take us out of the moment, replacing pathos with bathos, and reminding us that we are – after all – an audience in a theatre. The reason that Greek drama has continued to be meaningful is that it connects with people throughout history; these decisions by van Hove make it all the more difficult to establish this fateful connection.

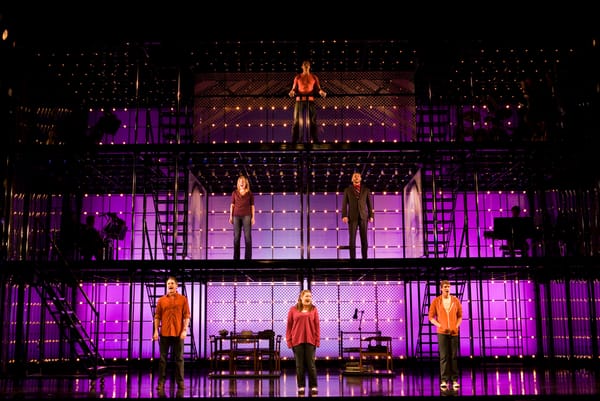

Such dramas lend themselves well to minimalist staging, and Antigone is no exception: a vast blank space, with a grave-like depression in the middle, and a blank circle at the back. At the beginning of the production, this circle moves back, revealing a vast round sun; as the play goes on the circle slowly revolves round, suggesting a single continuous series of events. This, combined with the music, which is largely minimalist organ drones, means that we are less in the ancient palace of Kreon than in a Philip Glass opera. It definitely works, allowing all the attention to be focussed on the actors. However, some unwelcome additions intrude on the minimalist setting: black sofas, typewriters, and shelves of video cassettes conjure up the atmosphere of a modern office, something that seems completely incongruous to the ethos of the play. The back of the stage is used as a vast screen, on which various scenes are projected: desert landscapes, blurred city scenes, and Antigone’s lifeless body. It wouldn’t be a van Hove production without some kind of modern technology, but – bar one point at the end of the play – it never intrudes on the action.

If this production of Antigone will be remembered for one thing it will not be for Juliette Binoche’s sterling performance, nor Ivo van Hove’s radical interpretation, but for the stunning new translation from Anne Carson, who handles the text with delicacy and wit. This play is urgent; it quietly demands to be seen, stealing your attention for the entire 100 minute run. A different take on a classic, van Hove’s production is disquietingly enjoyable, and unnervingly excellent.

Antigone is on at the Barbican Centre until 28th March. Tickets from £16 plus booking fee. Young Barbican tickets are available.