My name shouldn’t have to be ‘convenient’ for you

The importance of names as a part of one’s identity

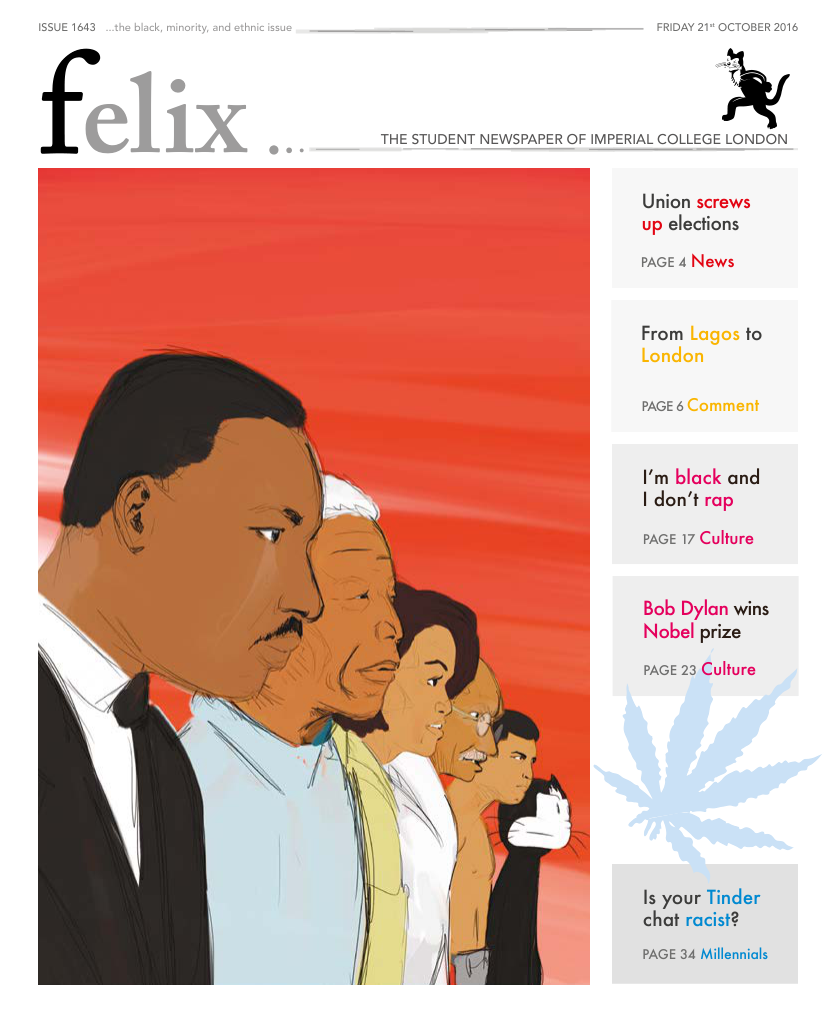

Most school children would celebrate at the glimpse of a substitute teacher. Even the most well behaved students are relieved to ditch their teacher’s pet persona momentarily. However, for some Black minority and ethnic (BME) students the arrival of a substitute teacher elicits a familiar dread. As the naïve teacher grasps the register, an awkward smile is instinctively plastered across the faces of BME pupils. A smile that is worn as a shield to deflect the imminent ridiculing laughter. A series of Western European names are called out seamlessly and then, at an expected point, an anxious declaration of “I can’t say this one” triggers a wave of giggles. The cackles are even more piercing when a teacher decides to butcher the pronunciation of a BME pupil’s name. This may seem trivial, but names are a fundamental aspect of self-identity. Hence the everyday derision of ethnic names has a negative psychological impact.

It is not surprising, then, that last year the UK government imposed name-blind UCAS applications

Names matter in recruitment, too. So much can be ignorantly inferred about a candidate based solely on their name. Countless studies have exposed the brazen rejection of applicants with ‘Black’ or ‘African’ names. It is not surprising, then, that last year the UK government imposed name-blind UCAS applications. The goal was to help increase participation in Higher education (HE) from ethnic minority groups. This new initiative was generally commended but a deeper issue still thrives. How do the aforementioned groups participate socially once within these HE institutions? Names cannot be concealed in social settings. Personally, on several occasions, my name has been a social handicap. People have abstained from conversing with me out of fear of pronouncing my name wrong. Sounds ridiculous but it is a genuine and palpable predicament for many BME students. The use of only pronouns ‘she’ or ‘he’ to refer to someone with a non-Western-European name is also very common. This too is problematic as it cultivates a relational barrier. Knowing and using someone’s name correctly is key to establishing a personal connection with them.

In response to employment discrimination and social awkwardness, many BME students choose to take on nicknames or ‘English’ names. The latter was an enticing notion for me prior to university. I deliberated over changing my first name to something more ‘simple’ but later refrained from doing so. In my opinion, changing one’s name to conform to an environment is nonsensical. It snubs unique culture and discards the story behind a name. It amputates identity. Slave owners in the 16th century understood this and so christened their slaves with Western names. Today, some Black Americans celebrate their inheritance of European surnames, and others detest it. Nonetheless, their choice of name undoubtedly influences their progression in life. Finally, there are examples which suggest society has moved forward; for instance, the succession of Barack Hussein Obama to presidency. Despite this, Jack Smith is still more likely to be employed than Oluwadamilola Alabi.