A tale within a tail

Ipsita Herlekar reveals the secrets of a well preserved dinosaur fossil

Strolling through the markets of the city Myitkyina in Myanmar, Lida Xing, a scientist with China University of Geosciences, Beijing, came across a block of amber that had preserved within it a fossil of a dinosaur’s tail from nearly 99 million years ago.

A collaborative study by palaeontologists from Royal Saskatchewan Museum, Canada, China University of Geosciences, Beijing, and University of Bristol, UK has provided new insights on the evolution of feather structure. The work has recently been published in the journal Current Biology.

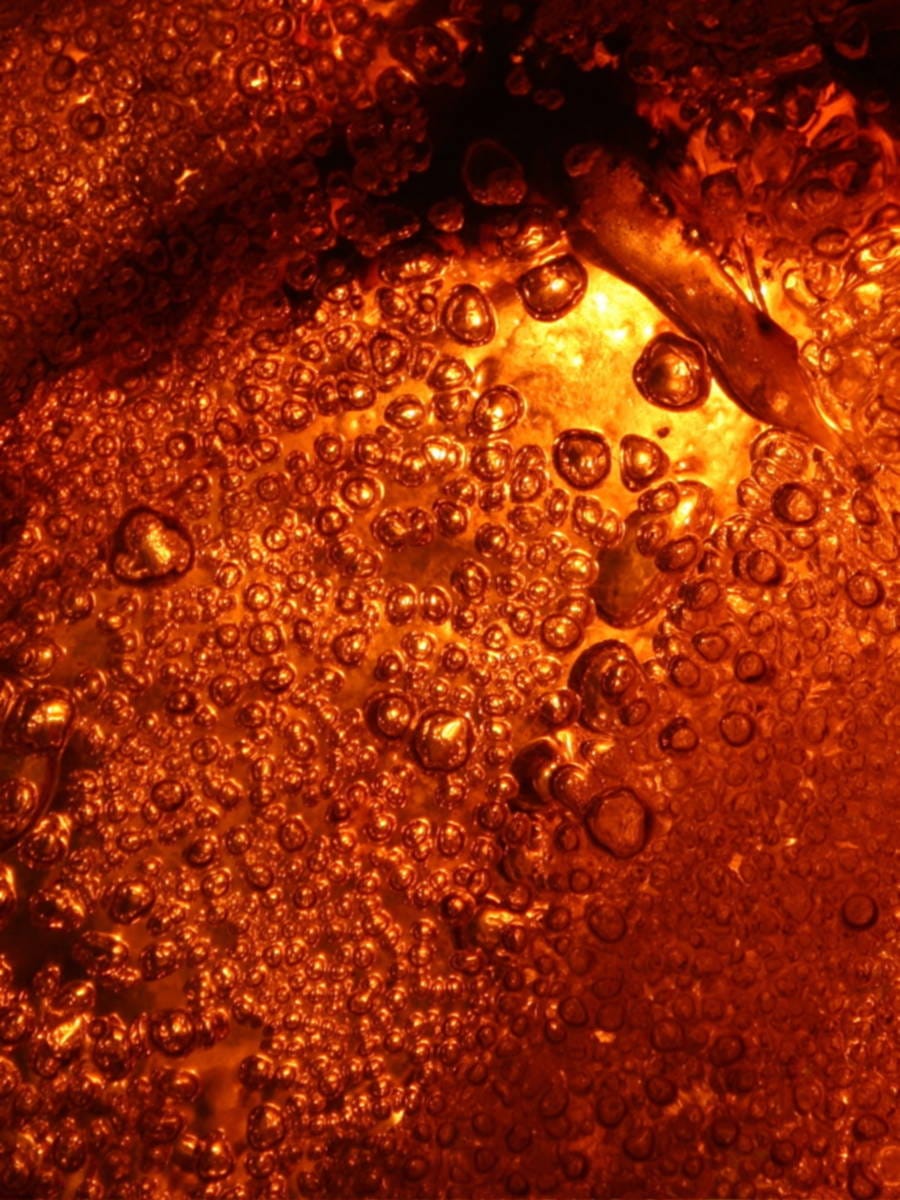

The fossil is that of a dinosaur belonging to a carnivorous group, the theropods, which probably lived sometime during the mid-cretaceous period. Observations suggest the tail colour to be brown on the top and paler in colour on the underside, lined by feathers all along its length. Unlike in present day birds or their ancestors, the vertebrae of this fossilised tail are not fused together, but are instead long and very flexible with the keel, the area where the flight muscles are attached: a typical characteristic of flying dinosaurs. The feathers found on this fossil differ from the ones that we see on birds today. The feathers of birds like those of the pigeons that we often spot strutting down the pavements typically consist of a long shaft called the rachis. Attached to the rachis are rows of fine filaments called barbs which are intertwined with one another by barbules, forming a tightly woven surface. The fossil specimen exhibits a well developed branching system of barbs and barbules, however, it has a poorly developed rachis. This clearly indicates the barbs and barbules to have evolved much before the rachis. Well preserved fossils are a rare find. They provide a snapshot of how life existed during the pre-historic times. Amber or fossilised resin is one of the best mediums for fossil preservation. So well preserved is this specimen, that the scientists were able to retrieve the soft tissues and even haemoglobin from the blood.

High-quality fossils such as these help palaeontologists to piece together the tale of how our modern day birds evolved from the flying cold-blooded reptiles of the pre-historic times. The scientists of this study believe that unlike some species of reptiles found today, this particular dinosaur couldn’t shed its tail but succumbed to an untimely death after getting it caught in the glue-like resin.