On the verge of a global health crisis

FELIX finds out what Imperial researchers really think

We do desperately need new antibiotics,” said Dr. Andrew Edwards, a lecturer at Imperial College London and group leader at the Medical Research Centre for Molecular Bacteriology and Infection. “What we have seen recently is the emergence of some strains [genetic variants of bacterial species] resistant to all of our different types of antibiotics,” he added.

“One of the big problems with antibiotics is that every time we make a new one, then we select for the bacteria that can survive in its presence. Every time we make a new antibiotic, very rapidly we see resistance arising and that has been happening since penicillin,” commented Dr. Gwenan Knight, an Imperial biomathematician looking for patterns in drug-resistance development and dissemination in the community.

The concerns about antibiotic resistance are nothing new – academics have been issuing warnings for decades. However, a new governmental report released last week by Jim O’Neill, the Commercial Secretary to the Treasury, predicts that consequences would be much more catastrophic if drastic changes are not implemented soon.

The 18-month study forecasts that by 2050, superbugs would be responsible for 10 millions deaths a year, the equivalent of one patient every three seconds, overtaking the death toll from cancer.

According to the report, the biggest contributors to antibiotic resistance are the large-scale use of antibiotics in animal breeding in a preventive therapeutic action (including last-resort antibiotics), the little incentive for pharmaceutical companies to develop new drugs and the lack of accurate diagnostic tools for doctors to pinpoint the source of infection in patients. The latter leads to antibiotics being prescribed against infections that could stem from viruses against which the drugs have no effects.

The report is trying to address these issues with a series of proposals for future antibiotic development and usage which, although welcomed, might not act as straightforward as expected. For example, while it suggests to drastically restrict antibiotic consumption in animal breeding, according to Dr. Knight “The Netherlands have been really good at decreasing use of antibiotics in agriculture, and they haven’t yet seen the decrease in clinical drug resistance in hospitals.”

Secondly, when it comes to the economic burden and the financing of R&D, the report suggests a monetary injection of 40 billion USD (approximately 27 billion pounds) every decade. However, the origin of the funding remains a subject of debate Among the solutions proposed, the most controversial would be a tax on pharmaceutical company revenues to create a new pool of funding for antibiotic research. This measure has already been criticized by the Association of the British Pharmaceutical industry, and might evolve in a national tax on antibiotic products instead. But both suggestions are highly contested by scientists.

“There’s two problems: firstly pharmaceutical companies already spend a small amount on antibiotic discovery, so taxing them would limit the amount of revenues they have available,” commented Dr. Edwards. “Secondly, because we have a National Health Service, taxing them [antibiotics] is just going to cost the taxpayer more to buy these drugs.”

The report is also proposing as a measure the adoption of an appropriate diagnosis prior to any antibiotic prescription, by 2020 in developed countries. The problem is that such diagnostic tests do not yet exist, or are not fast enough to identify infections like meningitis that develops extremely quickly.

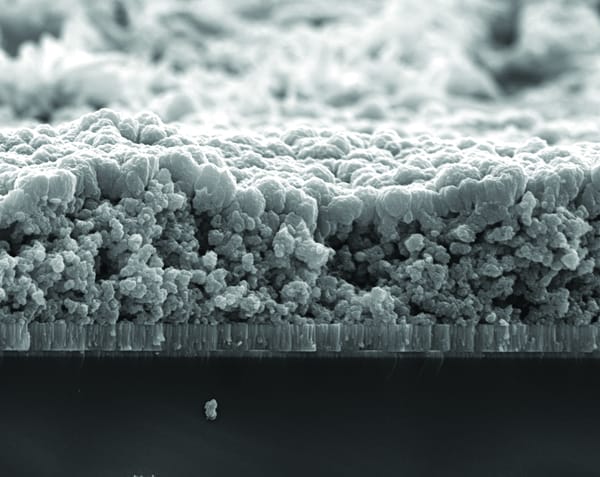

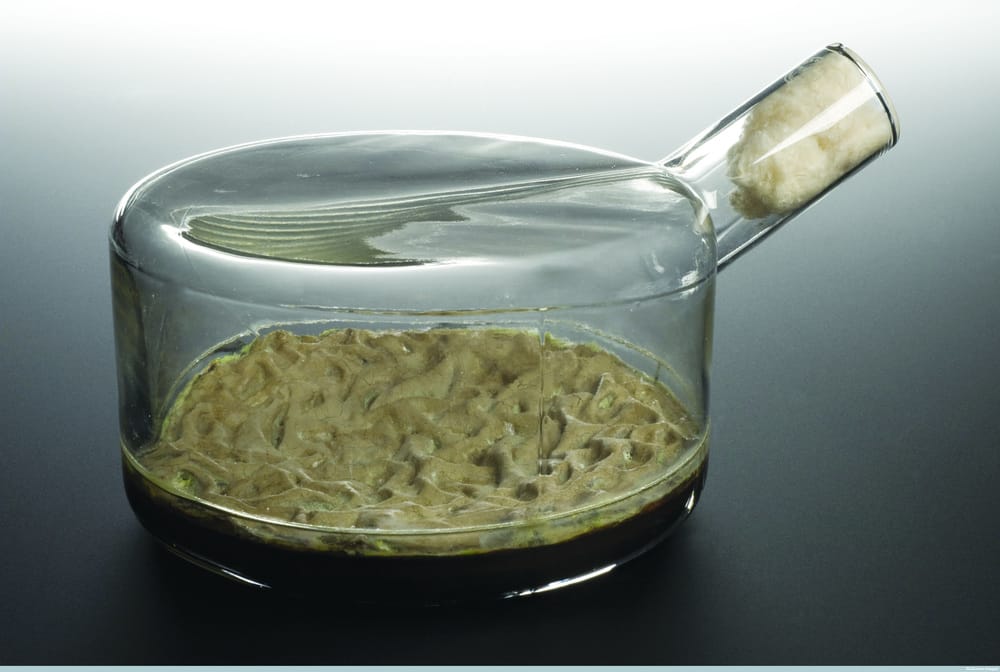

The fight against superbugs is extremely complex; there still remain many unanswered questions regarding the epidemiology of antibiotic resistant bacteria and many of the researchers at Imperial are trying to tackle them. For instance, as part of the Antimicrobial Research Collaborative, Dr. Edwards’ laboratory is trying to recycle outdated antibiotics by remodelling them with better efficiency and countering existing drug resistance mechanisms. He is also looking into disabling superbugs’ natural defences for the immune system to clear out infections without the help of antibiotics. Dr. Knight, in an Imperial-based NIHR-funded research unit, is trying to figure out using mathematical models the source of superbug infections. She explained: “In England we use about 80% of our antibiotics in the community and 20% in hospitals, but we don’t actually know where most antibiotic resistance is being generated.”

The alarming O’Neill report is a source of controversy not only within academia but also within the business sector, but there is one thing everyone agrees on: the crisis is imminent and there is an immediate need for global action on rather than just national policies. “If we happened to control antibiotic resistance just in the UK, it is going to be introduced from somewhere else around the world,” concluded Dr. Knight.