Lubaina Himid crowned winner of the Turner Prize

The Tanzanian-born artist who amplifies the stories of people of the African diaspora is the oldest-ever winner of the prestigious award celebrating contemporary British art.

The Turner Prize, which celebrates developments in contemporary British art, was awarded to Lubaina Himid on Tuesday night. Himid, 63, is the oldest recipient of the prestigious award, as well as the first woman of colour to be given the honour. Widely expected to win for her work that focuses on promoting the stories and voices of the African diaspora through drawings, printmaking and installations, Himid’s win was made possible by the lifting of the age restriction that has prevented artists over 50 years old from winning in previous years. It is speculated that another rule change may have benefited Himid: for the first time, the exhibition the artist curates specifically for the Turner Prize was taken into consideration. This meant that Himid was judged not only on her contribution to contemporary art in the past twelve months – as has been the case previously – but also the mini-retrospective of her work that she displayed at the Ferens Gallery in Hull, where the prize-giving took place.

The judges remarked particularly on A Fashionable Marriage – a piece Himid created in 1986 inspired by the tableau of characters in Hogarth’s Marriage a la Mode. The inclusion of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan as flirting lovers dates the piece, but its exploration of politics, the judges felt, was “resonant and relevant” today. Other pieces of note included in the exhibition was a series of pages torn from The Guardian that Himid has worked on for many years. In painting over sections of the newspaper’s pages Himid highlights the interplay between the headlines and the accompanying (often unrelated) pictures of black people. The juxtaposition of these elements, Himid argues, cements unconscious racial stereotypes – drawing caricatures of black people as victims and perpetrators of violence, imagery particularly potent as black people are rarely visible in other contexts in the mainstream media.

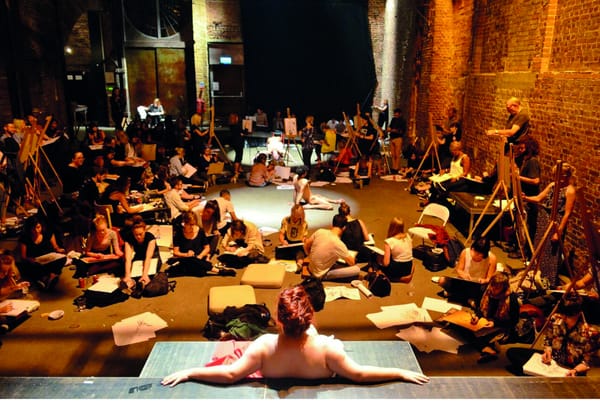

Himid, who was brought up in Lancashire and works in Preston, but was born in Zanzibar, Tanzania to a black father and a white mother, has made a career of making black lives more visible. In Naming the Money, which she conceived of in 2004 and was exhibited this year in the Museum of Modern Art in Oxford and Spike Island in Bristol – the shows that earned her the Turner prize nomination – Himid seeks to draw out forgotten figures from history and set them apart from the monolith that the word ‘slaves’ constructs. For this work Himid has constructed over 100 life-size cut-outs, each a representation of a slave. The figures, dressed in brightly coloured finery, and engaged in all sorts of different pursuits, from playing musical instruments to playing with puppies, each have accompanying text – written by and read aloud by Himid – gallery goers can listen to on a soundtrack, this text gives two names to each figure, the one they were born with, and a second they were given by their owners. As the viewer moves through the exhibition, each figure explains what they did before being sold, and what they do now as an enslaved person. Allowing these figures to give a sense of their history before they got on the boat that would take them to the West returns their dignity to them. The exuberance, the joy of these figures dressed up in flamboyant patterns and jewel colours is important too. Himid is not interested in “replaying their trauma”, but wants instead to celebrate their resilience, their capacity to beautify the world around them despite the atrocities committed against them – “they are stronger than history, that is the point. My figures say: ‘You tell me your story, I’ll tell you mine’” she said, speaking to The Guardian prior to her win on Tuesday.

Ironically, Himid, in her pursuit of making other more visible has gone rather unrecognised herself. Himid was “thrilled” to win, and thanked her long-time supporters saying “to the art and cultural historians who cared enough to write essays about my work for decades - thank you, you gave me sustenance in the wilderness years.” She speculated that she may not have received more mainstream acclaim because the public were not ready to receive her work until recently and the subjects she tackled were too “complex, many-layered” to sell newspapers.

Alex Farquharson, the director of Tate Britain, and the chair of the judging panel, said that Himid’s win was a reminder of the fact “that artists can experience a breakthrough in their work at any age”. Himid hopes the Prize, worth £25,000 previously won by Steve McQueen, Damien Hirst, and Grayson Perry, amongst others, will give her the prominence to work with more artists. As for the money, she’ll be using it to commission fellow artists perhaps, or buy a new pair of shoes.