Crossing the blood-brain barrier: the final frontier

Could we be seeing this development in medicine soon?

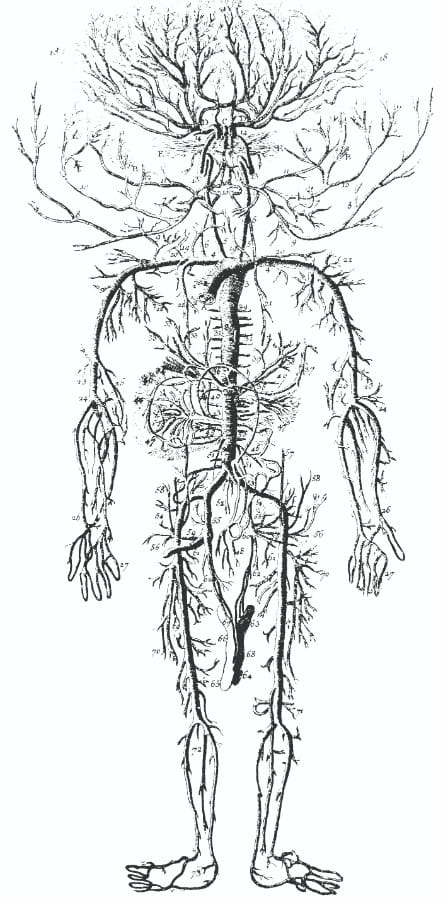

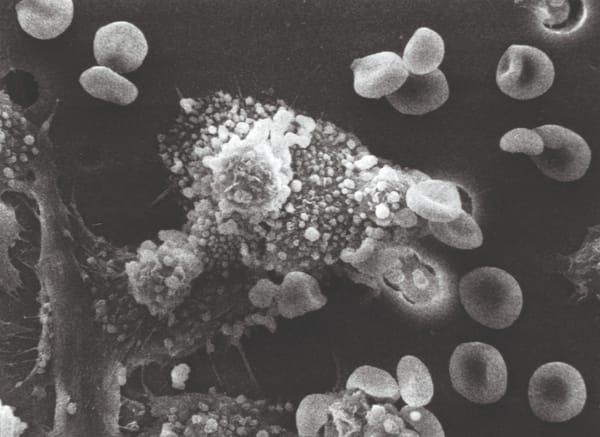

Gene therapy serves as a means to introduce artificial DNA into cells, which can then be transcribed and translated into proteins in order to treat various medical conditions. However, there remain many limitations for treating medical conditions associated with the central nervous system. Gene therapy works by packaging genes into specific carriers – often made from the outer shell of viruses, and capable of breaking into cells – which are then injected into the bloodstream. Once they reach and migrate into cells, they unload their genetic material. However, to reach the brain the carriers must cross the highly selective membrane called the blood-brain barrier. This barrier restricts most substances in the blood from passing into the brain, and, consequently, has rendered many drugs and therapies ineffective for use in the brain. A recent study, however, published in Molecular Medicine, examined and identified potential virus capsid structures which are able to cross the blood-brain barrier, thereby improving the reach of gene therapy.

This study examined adeno-associated viruses (a group of non-pathogenic viruses) for their ability to potentially improve transmission through the blood-brain barrier, and to enhance specificity for brain cells. Scientists compared the capsid features of two type of adenoviruses which differed by their ability to pass through the blood-brain barrier, and subsequently generated a library consisting of the individual parts of the capsid structure from the former virus. Using the library, they swapped out the corresponding parts in the capsid of the latter virus one-by-one. The result of each individual swap was noted, and the parts responsible for the change in their ability were identified, with their properties characterised.

The results of this study prove useful, since they show the capability we have to control movement through the blood-brain barrier. This provides the possibility of developing novel therapies which can target the diseases associated with brain and spinal cord – such as brain tumours – which have not proved an easy target due to this barrier. The current strategy involves providing a high dosage of the therapy, but this causes side effects by infecting non-target cells. By improving the specificity of crossing the blood-brain barrier, one can reduce the dose amounts and also the cost of therapy.

The study is promising, but requires further research to ensure the robustness for the proof of concept. As mice were the subjects of this study, it is likely that the findings may not be representative of human conditions, and thus the effectiveness of the study in human samples needs to be established. Furthermore, this study has only accounted for the challenges associated with crossing the blood-brain barrier, but the final gene therapy might still be limited by further complications such as improper dosage and possible side effects. Nonetheless, it kindles hope we may be able to target the brain-associated diseases which have for so long eluded the reach of medicine.