Life, Death, and Theatre with the Ekdahls

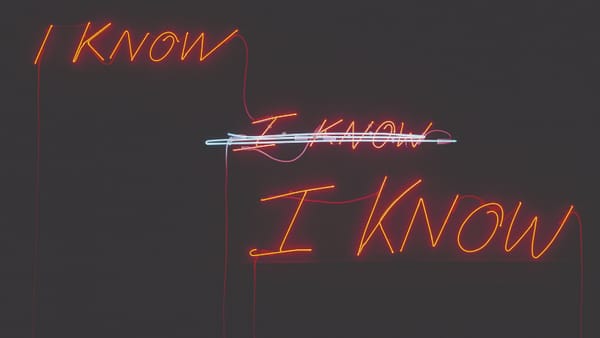

The stage adaptation of Ingmar Bergman’s semi-autobiographical work “weaves new patterns”.

Misha Handley steps onto the stage as Alexander Ekdahl and exclaims: “Ladies and Gentlemen, welcome to the longest play in the history of the world! ...Will it be boring?” Laughter from the audience marks a departure from Bergman’s original cinematic version. Beresford’s play has a feel-good vibe that sometimes feels like superficiality.

The play is indeed more than three hours long, with enough scope for two intervals – but this is necessary to cater to the rich and complex material, and the moments rarely drag. We are stimulated by the energetic atmosphere, which is enhanced by the special effects that accompany the dramatic action. They sometimes have a showy quality but occasionally, when combined with seamless acting, are very successful in creating an emotional ambience that holds the spectator in thrall of the actor’s performance.

Despite the title, it is above all Alexander’s perspective, that of an imaginative and sensitive child, which we experience throughout Stephen Beresford’s stage adaptation of Ingmar Bergman’s semi-autobiographical film. The stage version is moderately successful at retaining the integrity of the original in its exploration of broad existential themes, which may not be condensed down to an hour or so’s entertainment without cutting through the vital nerves and life-blood of this intricate web of human turmoil. The enjoyment is mostly derived from the drama being well-played by a skillful cast.

The play begins on Christmas Day – ideal for some reminiscing, in which Dame Penelope Wilton indulges and is comically pathetic without pathos. She is the matriarch of the theatrical Ekdahl family, charming and ridiculous with her imperious airs and affected manners, a hangover from her years on the stage. Dame Wilton manages to be nuanced with a touch of grey-haired dignity and much wistfulness for her bygone years. Though time hasn’t faded her romance with a family friend, and something in her manner convinces us she was beautiful in youth.

Her son is Alexander’s father: in the play, a childish, cocky embarrassment of a husband; in the film weary and passive with more than the usual amount of melancholy for his age. Before the drama yet unfolds, he delivers a speech that ought to sound pensive in shallow and unconvincing tones. It serves as a prologue to the play and meditates upon the purpose of theatre itself, in a strange intercrossing of worlds between the stage and real life; the purpose of the theatre, he concludes, is to provide a few moments’ refuge from the harshness of life, whilst mirroring it at the same time.

Fanny and Alexander succeeds quite well: fantastical elements of ghosts, telepathy and magic are effective at transporting us to a parallel world, and to some extent at obliviating the mundane. But these remain primarily tools that symbolize and abstract the character’s sufferings and allow us to enter their imaginations, seeing the world as they experience it. Beresford’s production seems to include a marked divide between the realms of the living and the dead which is less present in the film. Dinnertime scenes include the lavish menu being read out by two servants, whilst the Ekdahl family mime the merry enjoyment of simple pleasures. These sometimes occur right next to more emotionally tense scenes, such as one in which Alexander is wrestling with his fears and talking to the image of Death. This contrast between two worlds, designed to be unsettling though sometimes not subtle enough to feel coherent, provides a sinister undercurrent of evil foreshadowing, and attempts to lay bare the fears within each human being. The reconciliation of these opposing forces finds itself in the rambling speech of a joyful Ekdahl as he beholds his newborn daughter: “It is necessary and not in the least bit shameful to take pleasure in the little world - good food, gentle smiles, fruit trees in bloom, waltzes.”

Just as the dead remain in our minds, in the play they appear as stage figures. Alexander’s father returns as a serene white-suited apparition, his brutal stepfather as a Grim Reaper. In each case we are left wondering as to whether these are simply representations of traumatic grief or fear, or whether the supernatural is an element of reality in the plot. We are left unsure as to where the division between imagination and reality lies in Alexander’s mind. The ambiguity is concluded with a quote from Johann August Strindberg’s A Dream Play: “Everything can happen. Everything is possible and probable. Time and space do not exist. On a flimsy framework of reality, the imagination spins, weaving new patterns.”

3 Stars

Where? The Old Vic When? 21st February - 14th April How Much? From £12