Macbeth at the National Theatre

Superb directing, solid acting, and the importance of a good script.

Director Rufus Norris’s adaptation of Macbeth is perfect. Truly, I mean it. If I were to go through each individual aspect of the production, from the acting to the costumes, I would not change a single thing. But, did it leave me pondering a scene for hours after it had ended? Did it hit an intellectual or emotional chord that made me completely change my perception of what theatre or story-telling could be? No. Despite the utter brilliance of its components, this Macbeth is less than the sum of its parts.

Let’s start with the good; nay the very, very good The set design in Macbeth is immense. A colossal rising platform serves as the epicentre for much of the play’s action. Upon it, at the foot of it, underneath it. The sheer height of the structure adds another level of magnitude to the grandness of the play. And its ability to pivot from the background to the foreground allows the director to shift the intimacy of the play itself at a moment’s notice. It is an inspired piece of work by set designer Rae Smith.

Similarly, Norris’s and Movement Director Imogen Knight’s work on the interaction of the characters with the set is a thing of beauty. Transitions from one scene to the next are a ballet between actors and set – helped, of course, by the Oliver Theatre’s rotating stage.

The world inhabited by Macbeth is an apt choice by Norris and co: a post-apocalyptic shambles that wouldn’t seem out of place in the video game series Fallout. Every location a humble concrete shell and every surface covered in grimy plastic. Even the costumes, from Macbeth’s armour to his wife’s regal gown, are laced with muddied bin liners. It’s a world one can scarcely imagine fighting for, let alone killing for, which goes to further the insanity of the Macbeths’ actions.

The Macbeths themselves, portrayed by Rory Kinnear and Anne-Marie Duff, are good too. A bit bland at first, but as their characters begin the steep descent into madness, the actors come into their own. Kinnear’s dismay upon encountering the bloodied ghost of his friend –and victim – Banquo is intense but not hammy, while the resignation of his fate towards the end of the play is nicely juxtaposed with his ambition at the start. Duff is everything one could hope for in a Lady Macbeth. A cold and calculating figure in the first act, who takes charge of her relationship as Macbeth begins to crumble with guilt, only to become more unhinged than her husband ever was. Patrick O’Kane’s performance as Macduff is also a grower, with not much in the way of highlights in the first half, but a superb display when his character is overcome with the grief at the loss of his wife and son. Trevor Fox puts in an assured display as the desperate – and almost comical – Porter, and the three Weird Sisters are as enchanting as they are menacing.

Music also deserves special recognition. Spare the thrilling chaos of Macbeth’s ‘house party’ – think steam-punk-themed soiree hosted by Tom Waits – the soundtrack for the play comes from the bone-chilling hum of a bass clarinet and French horn. Almost Arabian in their melodies at times, the instruments are a brilliant accompaniment to the actors’ work.

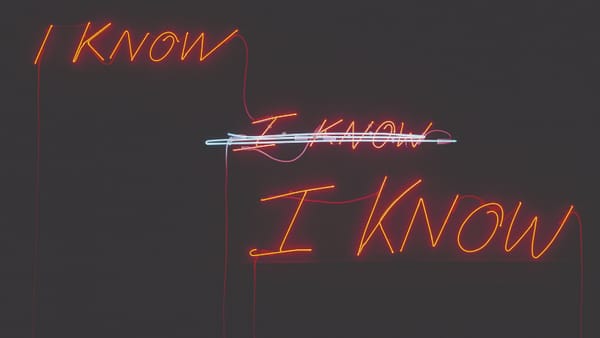

The problem with Macbeth is its inability to transmit the emotion, sadness, and horror being portrayed on the stage into the hearts and minds of the audience. That, in many ways, is due to the script itself. Macbeth is hard to like – or at least hard to engage with – simply because the title characters are so utterly detestable. From almost the moment we meet them, Macbeth and Lady Macbeth are overcome with their lust for power. Such detestability is likely what Shakespeare had in mind for the Macbeths – a perfect example of how ‘power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely’ well before the phrase was coined by Lord Acton in the 1800s. But when the title characters are the villains, not the protagonists, of the play, all the beautiful elements of horror fail to connect with the terrifying gusto they deserve. Even in what should be the standout moment of terror in the play – the sinister silhouette of a witch, watching high above the stage, as Macbeth and Lady Macbeth murder King Duncan – there is nothing to be afraid of, because the audience is in no way rooting for the Macbeth’s. Instead, they are willing their downfall or – worse still – apathetic to their fate.

Did Norris and his team make a mistake in framing Macbeth as a horror? Perhaps. Or perhaps – dare I say it? – the playwright is to blame.

4 Stars

Where? National Theatre When? Until 23rd June How Much? From £15