Prime time

Science writer Paulina Rowinska delves into the unpredictable world of prime numbers and describes why an explanation for their occurence would be such an important breakthrough in mathematics.

Had you recently visited the maths department, you would have felt like during the World Cup: students and researchers engaged in heated discussions while watching a 45-minute-long video. Only instead of a football game, we followed a lecture broadcast from Heidelberg in Germany.

On Monday 24th September, Sir Michael Atiyah, the esteemed Fields Medalist and Abel Prize winner, announced that he had proven the Riemann hypothesis - one of the biggest unsolved puzzles in mathematics. Cracking the problem posed by the German mathematician Bernhard Riemann in 1859 would be a major breakthrough. Some important mathematical papers are valid only under the assumption that Riemann hypothesis holds, so if someone manages to prove it, “many results that are believed to be true will be known to be true,” points out Ken Ono, a mathematician from Atlanta. Also, we can apply Riemann’s idea in cryptography, so the proof could potentially improve the security of online credit cards.

Prime numbers, those integers divisible only by one and themselves, serve as building blocks for larger numbers. 2, 3, 5, 7 and 11 begin this sequence, but later they start occurring increasingly less frequent, with gaps as large as 1550 (the largest gap found so far) between two consecutive primes. Their unpredictable occurrence has fascinated mathematicians for centuries. Riemann might have come closest to understanding the unpredictable occurrence of primes that had puzzled mathematicians for centuries. ‘Might have’, because so far his idea remains a hypothesis; a theorem lacking a proof - a proof desired so badly that in 2000 the Clay Mathematics Institute promised $1 million to anyone who provided it.

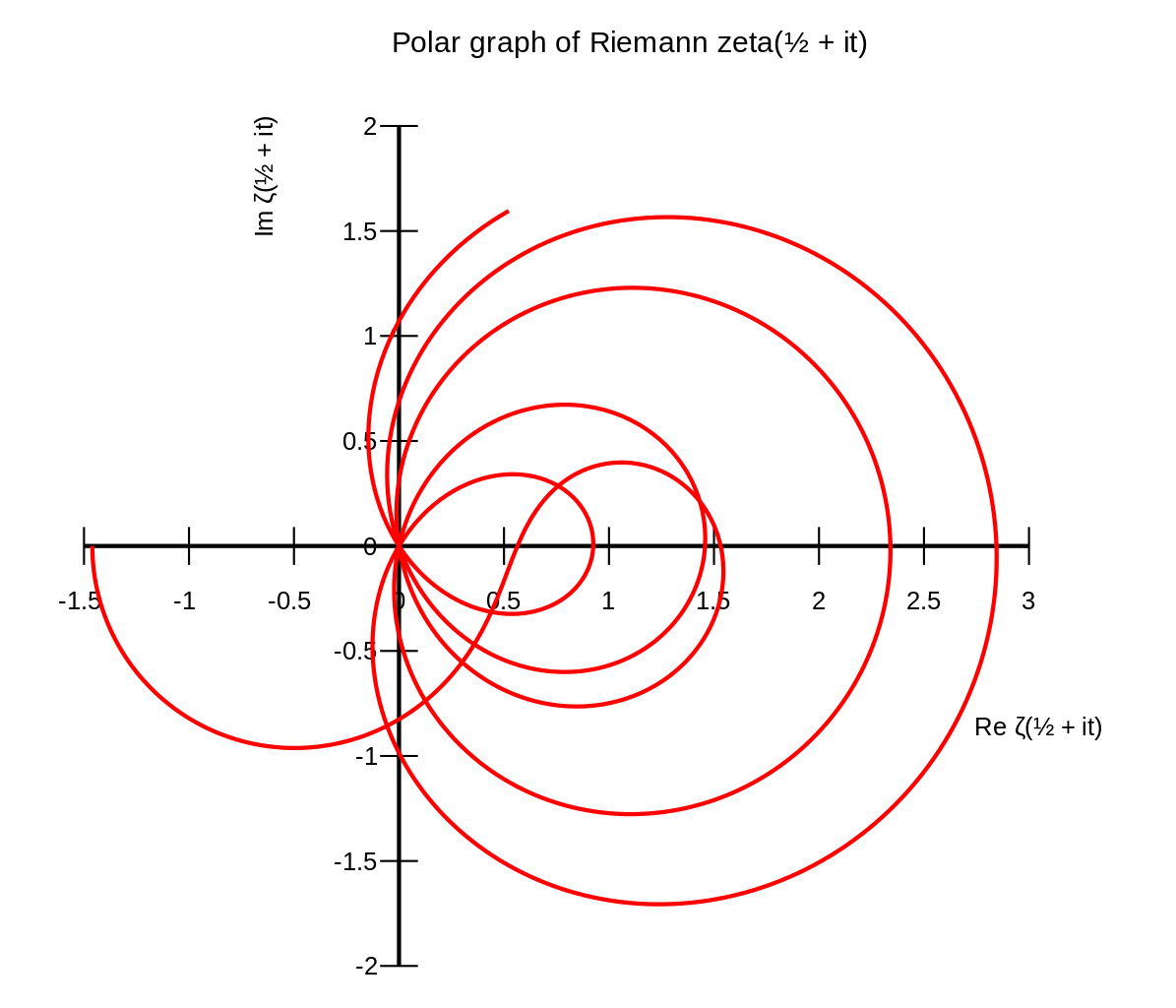

Riemann suggested that the frequency of prime numbers is closely related to an equation involving an elaborate function: the Riemann Zeta function. Powerful computers allowed us to confirm the hypothesis for the first 10 trillion solutions; more than the number of galaxies in the observable universe. However, if a cheeky solution that evaded Riemann’s rule was found in the next 10 trillion, we would disprove the hypothesis. Therefore, the proof must involve much more than just manual checking.

Many hundreds have tried and failed. Did Atiyah really find the secret to proving Riemann’s hypothesis? In other words, is his “simple proof”, as he describes it, correct?

Most mathematicians share a lot of scepticism about Atiyah’s attempt. “The proof just stacks one impressive claim on top of another without any connecting argument or real substantiation,” commented John Baez, a Californian mathematical physicist. The doubt of fellow mathematicians increased after Atyiha’s presentation at the Heidelberg Laureate Forum, because he focused on the history and importance of the Riemann’s hypothesis, rather than the details of the proof.

Numerous failed attempts to prove Riemann’s hypothesis, its importance, as well as the $1 million prize may mean that Atiyah might have to wait months or even years to get his proof verified, but if this happens, the already esteemed Atiyah will become a true legend.