President's pay protected as debts double

Universities risk a credit crunch in bid to compete for students

Imperial President Alice Gast has been named as one of the highest paid university heads in the country. The disclosure came shortly before it was revealed that Imperial has more than doubled its borrowing, giving it the largest debt of any British university.

Professor Gast receives a salary of £433,000, according to the College’s latest remuneration declaration, and reported in the Financial Times last month. She also collects deferred compensation of $375,000 (just over £294,000) each year in her capacity as director of multinational energy company Chevron, in addition to $10,000 from the Singapore Academic Research Council, and more than £9,000 from the UK Research and Innovation Board. This latter amount was donated to the College, which claims to have received £50,000 in donations from Professor Gast in the past financial year.

The disclosures included more detail than is required by regulatory standards. “Transparency is welcome,” Professor Gast said.

“I’m surprised by all the focus on money. I do my job because I’m passionate about it, she added.

Universities have recently come under fire for excessive vice-chancellor pay, sparked by the news that the former vice-chancellor of Bath University, Dame Glynis Breakwell, received a salary of £479,000. Imperial’s remuneration committee, which approved Professor Gast’s salary, justified the amount, saying it was “appropriate given the size, profile, and impact of the work of the College”.

On top of her annual income, Professor Gast has an official residence on Queen’s Gate worth £120,000 each year. As Felix has previously revealed, Professor Gast’s expenses are also among the highest in the country. In the past year, Professor Gast claimed almost £44,000 — more than the median salary for Imperial employees. Most of these expenses related to overseas travel, with the remainder claimed for taxis, gifts, and hospitality. The average expenses claim for Russell Group vice-chancellors over the same period was less than £10,000.

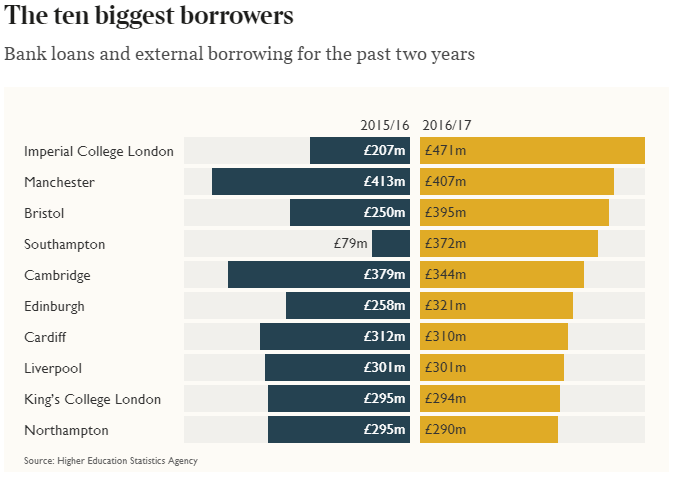

At the same time, Imperial more than doubled its borrowing, taking it from £207 million in 2015/16 to £471 million in 2016/17. This means the College has the largest loans of all higher education institutions in the country, according to a Times report using data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency.

Some of the money was used to fund the College’s expansion developments in White City. Following the opening of the Molecular Sciences Research Hub last autumn, Felix noted a series of complaints from members of the Department of Chemistry, which is now based at the White City campus. The emerging problems included two floors of the building being incomplete because “the whole project overran”, and facilities not working, in part because the building had been designed to a ‘one size fits all’ specification, resulting in labs requiring modifications.

The university sector now has debts totalling £10.8 billion. Higher education faces “unprecedented uncertainty” in the coming years, with Brexit and demographic changes threatening a drop in student numbers, and potential changes to tuition fees, which represent most universities’ main source of income. Numbers of EU students at Russell Group universities have dropped by 3% this year. Masters’ degrees numbers have decreased by 5% and there has been a fall of 9% in terms of PhD students.

Higher Education Policy Institute director, Nick Hillman said that “too many institutions are borrowing too much” and warned that some universities may face a “credit crunch” this year. Head of the Office for Students, Sir Michael Barber has stated that the body will not use public funds to provide bailouts for universities facing bankruptcy.

Financial pressure was cited as one of the reasons that universities were reluctant to continue with the current pensions system, which led to industrial action disrupting education across the country. As Felix has previously revealed, the College admitted to representatives of the University and College Union that it could afford to maintain its pensions contributions but had decided against doing so.