Stanley Kubrick: The Exhibition

Delve into the brilliant mind of one of the world’s most revolutionary filmmakers

What an opening. As the dramatic music of Also Sprach Zarathustra thunders in the background, the psychedelic hexagonal carpet from The Shining rolls underfoot. We enter a bright corridor of screens, Stanley Kubrick’s most iconic scenes flashing by as we get closer and closer to the main screen itself. It’s a homage to the beautifully symmetrical one-point perspective used in his cinematic shots, but also gives the strong sense of being, quite literally, sucked into Kubrick’s world of film-making. A fitting start to this new exhibition marking the 20th anniversary of the filmmaker’s death. Prepare to be wholly immersed in what went on in that brilliant mind - the mind that gave us some of the most unforgettable, genre-defining films of our time.

A single wood-panelled room awaits us. Loosely organised, it’s a bit like a cabinet of curiosities with Kubrick paraphernalia everywhere. The director’s chair sits proudly in a corner; one of his many Academy Awards is displayed nearby, alongside Sasco cards annotated by Kubrick himself and a letter from Audrey Hepburn. Original screenplays and scripts are exhibited in the centre of the room, each rumpled with use and scribbled over with handwritten notes by Kubrick’s own hand. It’s exciting to see his mark all over the source material: some dialogue resolutely crossed out, others emphasised with an underline and exclamation mark or two, and little storyboard sketches in the blank spaces.

Original sketches for costume and set designs litter the walls, as do scouting photographs taken in search of the ideal shooting locations. It’s much like a behind-the-scenes tour of the director’s studio. It’s easy to see his famed perfectionism, attention to detail and the sheer amount of preparation that went into each of his films. For Napoleon, a film on the French general Kubrick planned but never completed, rows of historical books on Napoleon fill a shelf on one side of the room - and that was just the pre-reading.

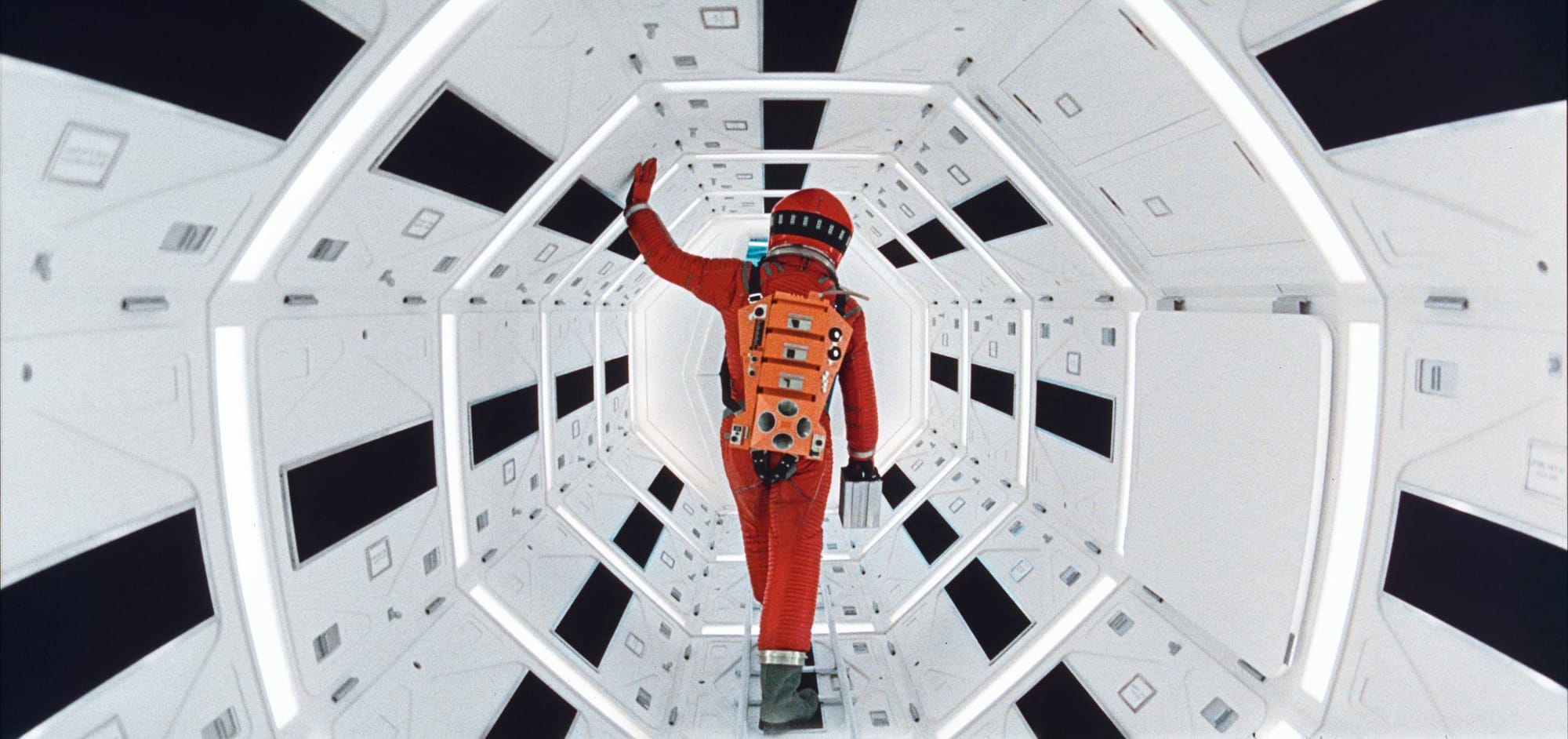

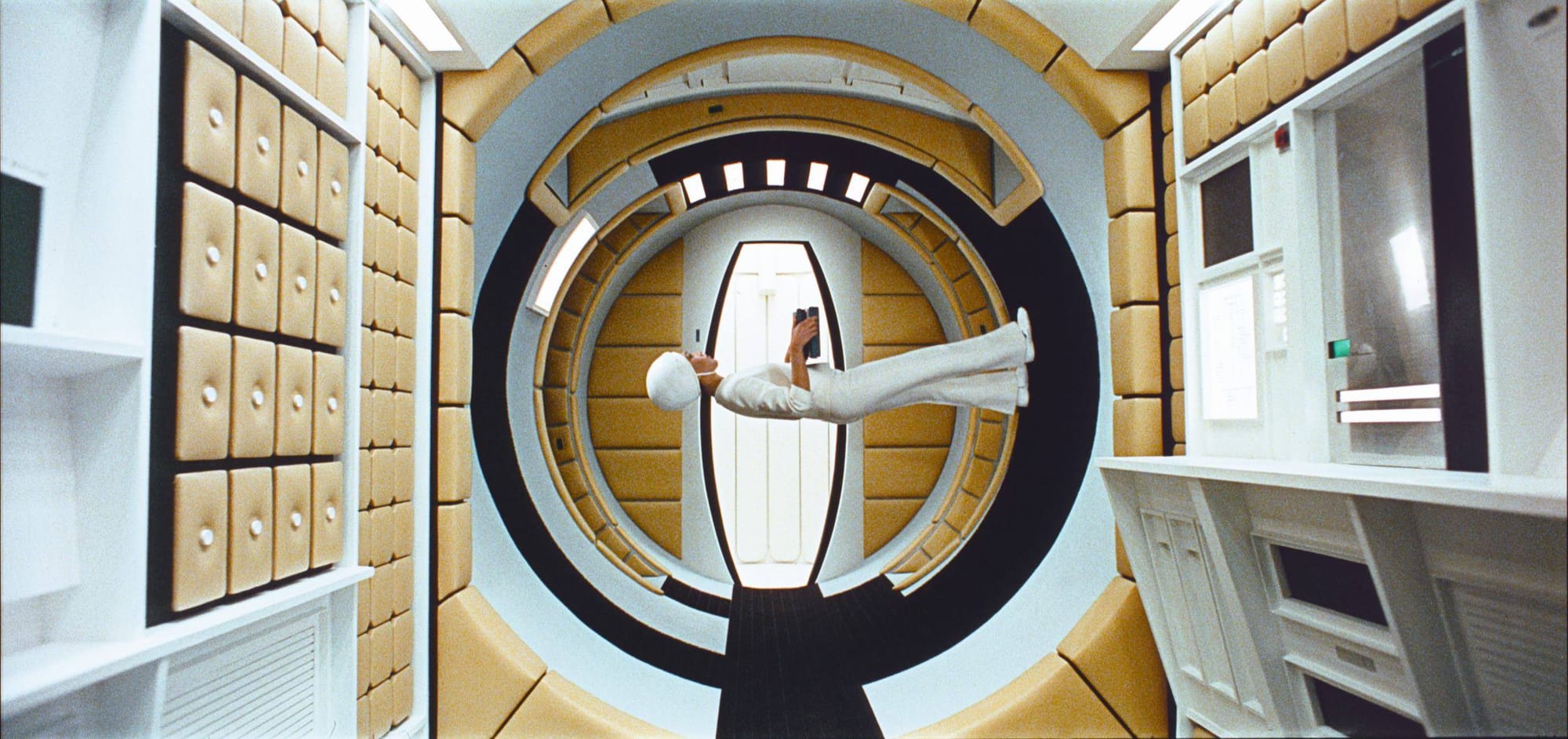

Kubrick was well-known for pushing the technical and artistic limits of filmmaking, and no exhibition on him would be complete without the seminal inventions that broke new ground in his films. Among the things not to be missed are the Zeiss high-speed lenses made originally for NASA space photography and adapted by Kubrick to shoot low-light candlelit scenes in his period drama Barry Lyndon. And, of course, the famous centrifuge set used to model the spaceship Discovery in 2001: A Space Odyssey ; taking 6 months and £580,000 to build, it enabled the creation of the futuristically continuous spaceship interior, one living space merging seamlessly with the next in a gigantic treadmill. Never one to be satisfied with current technology, Kubrick was always looking to use new techniques and new technology to achieve the effects he wanted. Also on display is the novel slit-scan photography used by Doug Trumbull to achieve the psychedelic light effects of the final ‘Star Gate’ sequence, representing a journey through space and time. While something we might take for granted now with the advent of CGI, this mind-bending light show was made entirely without computer effects and showed audiences something that had never been seen before in film.

The second, meatier part of the exhibition goes into the making of each of his films in glorious detail. The most famous scenes from each film are projected on large screens for viewers to get a taste of the finished product. Each section is rich with production photographs, original storyboard sketches and concept art, with iconic set pieces and costumes from each film on full display. There are some real gems here. Among these are Private Joker’s helmet from Full Metal Jacket, the slogan “Born To Kill” scrawled across it right next to a peace sign pin; the photoshoot of 14-year-old Sue Lyon, star of Lolita, staring provocatively over her heart-shaped sunglasses; Sir Kenneth Adam’s concept sketches for the War Room in Dr Strangelove, described by Spielberg as the ‘finest set ever designed’. Important work from other contributors to Kubrick’s films is well-acknowledged, from the graphic design of Saul Bass or Philip Castle to Milena Canonero’s beautiful costumes designed for Barry Lyndon.

The curators have also gone to the trouble to show both the things that might have influenced Kubrick and also the impact his films left on society. Don McCullin’s haunting photographs of the Vietnam War are prominently displayed in the section devoted to Full Metal Jacket, a film about the brutal impact of the Vietnam War on both soldiers and civilians. Meanwhile, a series of irate letters from the public capture the controversy stirred up by the violence of A Clockwork Orange and the sexualisation of a teenage girl described in Lolita. There are also fascinating tidbits about the creative process behind each film. For Eyes Wide Open, Kubrick had to shoot a story based in NYC on the streets of London - his meticulous insistence on authenticity led him to have his assistant painstakingly photograph the whole of Commercial Street, one photo at a time, on a 12-foot ladder.

The exhibition ends, fittingly, with his most famous and technically challenging work, 2001: A Space Odyssey. It was the genre-defining film that would shape the way we thought about futurism and science fiction forever. Capturing the sense of space exploration and futurism of the time, Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey was a realistic view of a plausible future, predicting things of our day like iPads and current worries about sentient artificial intelligence. Kubrick and his team imagined this possible future in stunning detail, ranging from technical consultations with IBM for the design of intelligent computer HAL-9000, right down to the furniture, watches, clothing and even cutlery used in his vision of 2001. On display here, though not included in the film, is even an intriguing range of ‘futuristic makeup products’ envisioned by cosmetics giant Coty for use by the ladies of 2001.

It was characteristic of Kubrick, perhaps, to craft whole new worlds for each of his films, although only part of them would ever be seen by audiences. While this made him set punishingly high standards for his staff and chosen actors - there’s a bit in the exhibition about how he made Tom Cruise walk through a door 90 times for Eyes Wide Shut - it also gave him the ‘magic’ he looked for in front of his camera, and which filtered down to us as audiences. There certainly is something magical about watching a Kubrick film. Whether horror, science fiction, war film or even historical drama, he elevated every genre he ever turned his hand to, without losing his distinctive style.

The thing about magic is that it can’t be explained. But the Design Museum’s breathtaking retrospective gives a glimpse of what went on inside the head of this eccentric, influential and groundbreaking director. An exhibition that will satisfy even the most hardcore Kubrick fan, and leave you with a strange desire to watch all his films in one sitting.

- 5 stars