The Rise of Private Equity

Before the financial crisis, private equity investors followed closely the “buyout” manual pioneered by Henry Kravis and George Roberts when they founded the firm KKR in the 1970’s. Essentially, they would acquire companies whole, then they would cut costs and load them with low interest rate debt. For a while this was very successful. Earlier this year the private equity firm Blackstone sold its 15.8 million shares in Hilton Worldwide Holdings, bringing an end to an 11-year relationship that ended up as the most profitable private equity deal on record ($14 billion in profit meaning the firm tripled its investment). Blackstone took the hotel private in 2007, with the firm putting up $6.5 billion of equity. The firm later suffered during the financial crisis but after some more cash and restructuring of Hilton’s debt, Blackstone took the company public again in 2013. The shares had more than doubled at the time of the sale. Despite this, many critics said this method was comparable to cash-rich private equity firms playing a risky game of musical chairs.

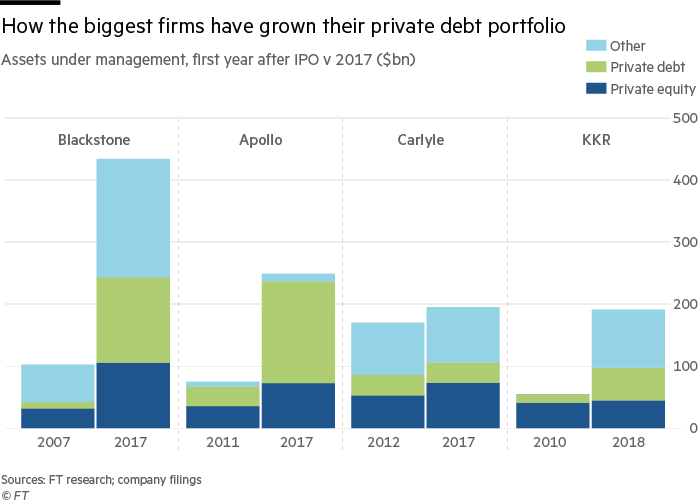

Now the biggest firms, including Blackstone, have changed course joining a new breed of lightly regulated “alternative” money managers that have filled the void as banks are forced to retreat from risky deals. Unlike mainstream banks, which are dependent on deposits and short-term funding, these funds raise capital from long-term institutional investors such as insurance and pension funds. They provide a crucial source of credit, sometimes in very unconventional ways, for companies that have too much risk to tap into the bond market. In 2013 Codere, a Spanish gaming firm, faced imminent bankruptcy. Its bonds were trading at just over half-face value. Blackstone offered it a cheap $100m loan, with a catch. Blackstone had bought credit derivatives on Codere’s debt that would pay out about $19 million if they defaulted on a bond payment. So Codere delayed a payment by a couple of days to prompt a “technical default”. Consequently, Blackstone got its pay-out and Codere lived to fight another day. The investors who sold Blackstone credit derivatives had essentially bet that Codere was going to live up to its bond payments. Without the loan, that most likely would have been the case and those investors would still have paid for their error. Similarly, in 2017 Blackstone bought $33 million worth of credit derivatives on Hovnanian, an American construction firm. It again offered cheap financing on the condition that it trigger those derivatives to pay out. One of the credit default swap sellers, Solus Asset Management, a hedge fund, was denied an injunction to stop the technical default. Even though America’s Commodity Futures Trading Commission suggest technical default may count as market manipulation, the company falls under the Securities and Exchange Commission, which has said nothing. Credit default swaps were intended as a hedge against losses from defaults, not a bet on whether a firm defaults on its liabilities. However, it is this alternative thinking that has led to private equity firms being so successful. Funds are raising more capital than they can spend. According to Thomson Reuters, buyout volumes were up 27% year on year in 2017 and can be expected to accelerate this year, with a record $1.1 trillion of cash pledged by investors. “The private equity fundraising environment has been extraordinary” says Alison Mass, global head of the financial and strategic investors group at Goldman Sachs. “We are in frequent dialogue with our largest clients regarding targets in excess of $10 billion”. The main propelling factor for the boom is the same one that fuelled the industry before the 2008 crisis: cheap debt and huge wall of cash caused by the huge amounts of bond buying by the central banks, keeping rates down. The size of recent deals is beginning to surpass those pre-crisis peaks with companies increasing their dependence on debt financing.

What is more worrying is with all this unspent capital, private equity firms are now beginning to eye up buying banks. With Blackstone’s €1 billion purchase last week of a 60% stake in Luminor, a Baltic lender whose return on equity lags behind most other Nordic banks, economists are worried this marks the start of a series of acquisitions. Since both sectors are highly leveraged boosting one with the other would be a very bad idea, a clear example being the spiralling levels of leverage that caused the financial crash a decade ago.

So should investors return to the asset management industry for capital returns? Interestingly, Larry Fink who runs BlackRock (the world’s largest asset manager with $6 trillion of assets) was the colleague of Stephen Schwarzman who runs Blackstone (the largest private equity firm), until the two companies split in 1995. Yet they both have very different views on investment and management strategies. BlackRock stands for computing power, low fees and scale. It mainly sells passive funds (including ETFs) to institutions and the masses. Meanwhile, Blackstone represents a combination of brain power, high fees and specialisation. It uses leverage and changes in the management of firms to make them more valuable, clients being the institutional and the rich. Measured by sales, profits and cash returns to shareholders, BlackRock is on average 31% larger, raising seven times the amount of net client money cumulatively over the past decade. Additionally, BlackRock made roughly $2.9 trillion of profits over the past 10 years compared with $202 billion for Blackstone’s clients and BlackRock is valued on 25 times profit, versus 11 for Blackstone, suggesting that investors prefer its simple structure, thinking it will grow faster. Having said this, the passive funds BlackRock provide are highly correlated with the overall stock-market, faring well in the recent bull run on the S&P 500, but a slight crash may put the firm in serious trouble. As well as this, although BlackRock has swathes of power in corporate America, holding voting rights in a large number of large cap companies, the more it uses its power to influence these firms, the more regulators will scrutinise it.

This is partly why investors are now seeking alternative investment strategies, such as private equity firms. Even though asset managers can provide stable returns, it is becoming harder and harder to generate alpha (gauges the performance of an investment against a market index or benchmark which is considered to represent the market’s movement as a whole). Therefore, institutional investors are looking to more creative schemes to give them that edge. But you can’t beat the market forever.