A Distortion of Orientalist Art

Innocent romanticism, an intrigue for exoticism or a mission of western hegemony?

2 stars

This tone is set by the very first piece in the exhibition, the Prayer. This painting by Frederick Arthur Bridgman, is supposed to capture two individuals in a mosque, engaged in the act of prayer (salat). The subject in the foreground stands with both hands outstretched at his sides, face up to the sky, while the other arches his back and holds a palm up in front of his head awkwardly. As a Muslim, I can inform you that neither action is a legitimate stage in salat and the scene actually contradicts the humility and rigour inherent to the ritual.

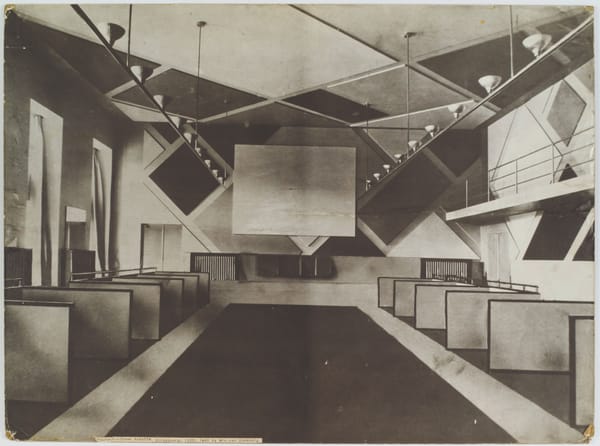

The question of artistic intention is contentious, and particularly sensitive in the case of western observation of cultures where imperial hegemony is historically rife. The colonial context of the orientalist movement saw the commissioning of large quantities of art by North American and European elite to perpetuate a political agenda of white superiority. This is demonstrated in much of the art displayed in this exhibition – local people of the Middle East and North Africa being presented as idle or primitive in scenes capturing everyday life. An extension to this is the completely fabricated and perverted imaginings of the harem (domestic, women-only spaces that are intended for the preservation of privacy and modesty). Paintings such as The Turkish Bath by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres which depicts a group of nude women lounging in suggestive poses, ironically seem to obsessively fetishise the harem, whilst portraying it as an animalistic Islamic practice to elite western audiences. In the exhibition’s final piece, contemporary Turkish artist Inci Eviner protests and satirises this sexualisation, presenting her own fictitious Harem in a looped video of women engaged in bizarre, possessed interactions.

It is undeniable that some level of genuine admiration for the Islamic world is suggested by some of these pieces – for example, Jean-Baptise Vanmour’s illustration of Ottoman wealth and power in scenes of diplomatic ceremonies. Despite this, an air of glib appropriation and ignorance is often maintained – John Frederick Lewis’ self-portrait as a ‘Middle Eastern’ shows him draped in a sash that is actually Indian. This is supported by the fact that many of these pieces were created by artists who had never travelled to the places they portrayed, instead relying on props and other art for inspiration. Indeed, it would seem that art with exotic motifs was the aim, rather than art with accurate Islamic influences. Though the exhibition acknowledges orientalism’s misrepresentative nature, the captions predictably offer fairly subdued criticism, settling for terms such as “romanticised” and leaving it to the viewer to consider the nuanced and often deliberately deceitful nature of the orientalist movement.