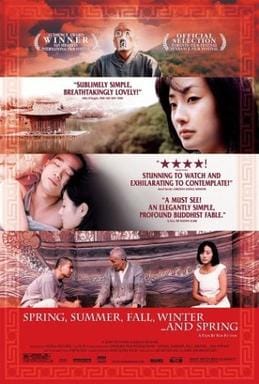

Classic film of the week

Film editor Oliver Weir looks back on the classic film Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter...and Spring about a monk's apprentice who lives on a pond in rural Korea

Spring, Summer, Fall, Winter...and Spring, or ‘Spring...’ as I shall call it, follows the life of a monk’s apprentice who lives in a floating monastery on a pond in rural Korea. Out on that placid lake, all the nuances of a lifetime are displayed. We see the best of it, and the worst. We see joy, anger, sorrow, and pleasure. We see romantic love kindled one day and extinguished the next. We see apprentices come and masters go, and see those who were students one day become teachers the next. We see the same lessons being learned time after time, with new generations being similarly at ease and at odds with the same old condition. And all the while only we, the audience, live long enough to observe these impalpable repetitions.

Out on that placid lake, all the nuances of a lifetime are displayed

‘Spring...’ presents itself on two scales: the first is to see the film as a story of humanity and of those ideas that all of us must come to terms with, the second is to see it as a detailed portrait of a man’s life, with each event and emotion being considered without distraction. Each perspective comes with some alienation, and yet each is able to find solace in the other. Sure, the monk throughout his life makes many mistakes and does many stupid things, but this, as each generation proves, is not an aberration, it is a certainty—and in this he should not feel alone. Likewise, when seen on the larger scale, these inescapable cycles that forever repeat can make life seem doomed, lonely, and meaningless. When presented with this, we can find solace in the small scale: we see that there was clear meaning in the times he laughed, in the times he loved with all his heart, and in the times he found some peace in religion.

Kim Ki-duk is able to develop each of these perspectives with a dispassionate yet admiring gaze. The natural setting—of a monastery floating on a still pond, surrounded by colourful flowers and ancient pines—is extremely effective in getting us to take a breath and slow down to a meditative tempo. The absence of dialogue and of a world outside that little pond focuses the mind on the character’s actions, and on the effects thereof. The main example of this is the young boy’s anger; it percolates benignly through the years (much to the displeasure of his teacher) until it eventually boils over into action. We are able to track this anger from its relatively harmless inception all the way to its bloody end. During this episode of the boy’s life, and in all others, we are never required to judge. No single explanation is held up as the truth; perhaps the boy killed because of karma, or perhaps, in a state of helpless credulity, he followed the first thing that resembled an answer.

I can certainly see how some would feel isolated, perhaps even demoralised, after watching ‘Spring...’. There is a strong urge to see things either entirely on a grand scale, or entirely on a human scale, and in both one can start to feel the clutches of nihilism. The answer is to realise that there’s really only one scale, and that the battle between the distant and the local is really no battle at all. ‘Spring...’ concludes by showing us that single scale, that contented state of resignation which acknowledges that, although we may be frail and finite things, while the universe is vast and will go on without us, there is, as Wordsworth once said, ‘A grandeur in the beatings of the heart’. For some, this brief delight will still not be enough; and yet, as this film lays bare for us, and as history so callously and continually reminds us, it may well be all we have.