The need for speed and carbon neutrality: F1 2026

Redesigned energy management, fully sustainable fuel and more to be expected next season in Formula 1’s most sweeping rules change to date

Formula 1 has long been recognised as one of the prime examples of engineering, in both its frantic search for technical perfection and harmonious demonstration of the power of teamwork and consistency. With only three races left in the 2025 calendar, all eyes (that are not hyper focused on the most riveting driver’s championship battle since 2021) are looking at next season – and the changes it will bring for the 22 drivers, hundreds of engineers and millions of fans.

A quick look back to the past

The 2014 season introduced hybrid power units, a revolutionarily sophisticated system that combines an internal combustion engine with an electric recovery system. The latter is formed of two motor/generator units (MGUs): one that harvests electric energy upon braking (MGU-K) and another that recovers energy from hot exhaust gases that drive the turbine (MGU-H). These parts work in unison to form an energy loop, ensuring efficient recovering, storage and deployment.

Half electric, fully transformed

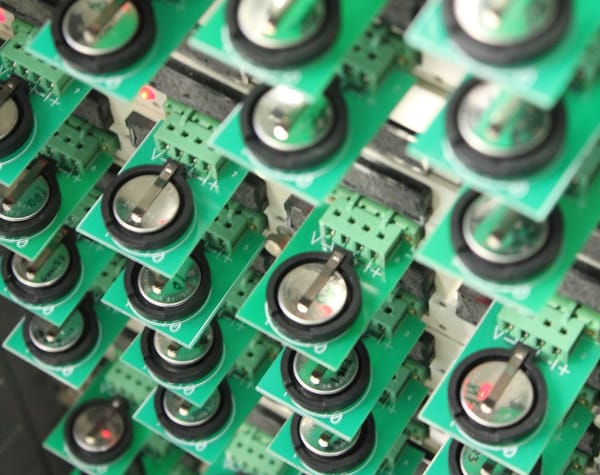

2026 will see Formula 1’s most sweeping overhaul in a decade, at the core of which are engine changes. The design will now honour simplicity, eliminating the MGU-H and increasing the maximum power output of the MGU-K by almost three-fold. This brings the electric system to around half of the car’s total power, as opposed to the previous 80-20 split. The total output will approach 1,000 horsepower, compared to the 900 since 2014 (and the 150 horsepower found in typical road cars…we’re talking speed!). Managing such energy flow brings engineering challenges in the temperature management of the batteries and controlling energy release: the car now relies entirely on braking events for harvesting, so must balance energy use carefully across a lap.

For almost 15 years, the drag reduction system (famously known as DRS) was the only component of the car that could increase airflow mid-race and increase speeds down allowed straights by up to 30km/h, delivering countless race-determining overtakes and battles. To accompany the renewed MGU-K, this system will be substituted by mobile elements in the front and rear wings that will allow opportunistic storing and deploying of the electric energy. The car will now be in either straightline mode, operating with low air resistance and deploying up to 350kW energy to the rear wings, or cornering mode, where the car will focus on harvesting that energy during braking, the MGU-K acting as a generator. The previous drag reduction system was only allowed to be used when a car was within one second of the car ahead: this new system is now track position-independent, which should allow for drivers to catch up to each other quicker and deliver more fights.

Aerodynamics, hybrid systems, and control electronics aren’t separate tools anymore but all part of one energy management ecosystem where the MGU-K dictates how the car uses air, grip, and speed.

Racing toward net zero with 100% sustainable fuel

Another change introduced in 2014 was E10 fuel, consisting of 90% fossil gasoline and 10% renewable ethanol derived from plants. While nodding toward sustainability, its heavy reliance on crude oil was not enough to achieve the FIA’s (Formula 1’s governing body) objective of achieving carbon neutrality by 2030.

2026 rules introduce fully sustainable fuel that can be used in any combustion energy without modification, especially relevant considering there will be a record-breaking six confirmed engine suppliers on the grid. The fuel will consist of non-food, non-fossil carbon sources, like captured carbon dioxide and farming industry or household waste. The carbon dioxide taken from the atmosphere or waste streams used for fuel production will equal the amount emitted from the tailpipe upon combustion, establishing this ecological measure under the net-zero, closed-carbon loop umbrella and not as a zero emissions solution.

The hierarchy between these top cars and the billions of road cars is interestingly reversed when it comes to fuel testing: F1 is being used as a testbed for large-scale synthetic fuel development by F1’s current fuel suppliers (e.g. Shell and Aramco). Because the cars work at extreme temperatures and engine revolutions, if a fuel works reliably under race conditions, it will be much more obviously applicable to vehicles where electrification is harder, like heavy transport, as well as for regular road cars.

Race by race, lap by lap

Smaller, narrower, lighter cars combined will show 55% less air resistance, and their quicker acceleration will also mean a higher speed down straights. However, cars will be more constrained on corners due to energy limits, making the expected lap time for cars around one second per lap slower at the start of next season. The alleged creative freedom allowed by the FIA to the engineering teams should however bring exciting new upgrades throughout the March-November 2026 championship.

Some tracks will not produce enough energy to maximise power on all the straights, leading to a flashing warning light shown in the car known as clipping. Because the battery is now responsible for more of the power delivered to the car, clipping is a more obvious issue. For this, the FIA has implemented a case-by-case regulation of the rate at which the energy can be used from the battery in these more draining tracks e.g. the classic Monza Grand Prix.

With the FIA also limiting maximum battery charge, the qualifying sessions, which determine the order in which the cars begin the race, should be more focused on a “pure expression of aggression”, as expressed in the FIA press release. With higher electrical power and deployment strategies, qualifying could see a wider range of lap times, rewarding drivers who better understand battery management and thermal limits.

What to expect on track

With drivers themselves being responsible for the switch between straightline and cornering mode and a completely redesigned MGU-K role with much more sophisticated energy management, the 2026 F1 model has received plenty of online backlash since the FIA press release in June. One of the main criticisms aligns with driver Lance Stroll’s opinion, stating that such complexity is neither necessary nor wanted, as he stated he remains hopeful for “less of an energy/battery/championship science project, more of just a Formula 1 racing championship”. Charles Leclerc, who drove the simulator upon tests earlier this year, described the experience as very far from simply lovely: “it’s not the most enjoyable racing car I’ve ever driven”. So, is the future of racing really in danger?

While the only thing we can do is keep watching, it is safe to say that mastering these new drastic changes demands a racecraft that combines mental stamina with mechanical expertise from both the drivers and engineers. Starting March 2026, the new regulations, if anything, promise change. Any setbacks, learning curves, or unforgiving moments will serve as testaments that even the best in the world aren’t perfect, one of the longest-standing moral lessons of the pinnacle of motorsport – which should probably be more present amongst us Imperial students!