New Alzheimer’s drug rejected by NICE

Despite setbacks, the quest for groundbreaking Alzheimer’s treatments continue.

On the 23rd of October, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) made headlines for its decision to reject donanemab – a new Alzheimer’s drug – for use in NHS England, citing budget constraints. This comes after a similar pioneering Alzheimer’s drug, lecanemab, was also rejected by NICE despite being approved by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA).

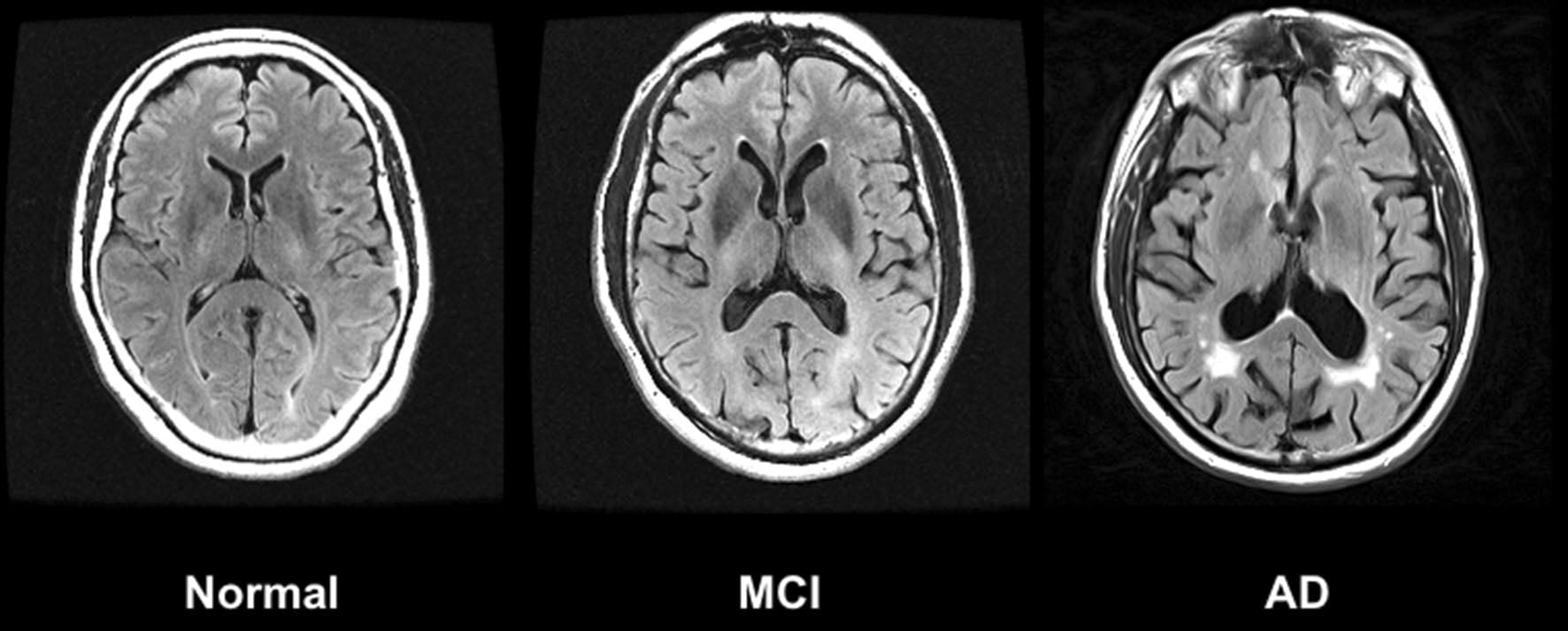

Both drugs have been viewed by researchers as a potentially big step forward in the fight against Alzheimer’s, as they target known causes of the disease rather than just tackling symptoms like most drugs currently available on the market. Donanemab works by binding to amyloid — one of the proteins, along with tau, that is associated with Alzheimer’s disease — to clear buildup in the brain. Although not a cure, the drug has been shown to slow the progression of cognitive decline in patients with Alzheimer’s disease.

However, this comes at a steep cost, both due to the price of the drug itself and the labour and equipment required to monitor patients for dangerous side effects. It is this cost that led NICE to reject donanemab for use on the NHS. Helen Knight, director of medicines evaluation at NICE, stated that the potential benefits of donanedab are “just not enough to justify the additional cost to the NHS.”

This decision to reject both drugs for use in the NHS has been met with frustration and disappointment by charities. “While these drugs are not cures and come with the risk of side-effects, trials show they are the first treatments to slow the decline in memory and thinking skills linked to Alzheimer’s, rather than just alleviating symptoms,” stated Hilary Evans-Newton, chief executive at Alzheimer’s Research UK, following the decision. There are also concerns that this decision may only widen the pre-existing disparities in healthcare access in the UK; since donanedab has been approved by the MHRA it will be available for use in England, just not on the NHS, and therefore some are worried that it may create a two-class system comprised of those who can afford private healthcare and those who cannot.

However, others are more understanding of the decision, particularly in the context of an NHS that is already at a financial breaking point. For example, Professor Paul Morgan at the UK Dementia Research Institute Cardiff labelled the drugs as “eye-wateringly expensive, difficult to administer and potentially harmful”.

Another major concern of some charities is that this decision by NICE may dissuade scientists from carrying out pioneering research into Alzheimer’s in the UK. As a spokesperson for Alzheimer’s Research UK stated, the announcement “risks signalling that the UK is no longer a good place to launch new dementia treatments.”

However, this was seemingly instantly proven incorrect on the 24th of October, when the Dementia Trials Accelerator was launched by the UK Dementia Research Institute and Health Data Research UK, which aims to enrol tens of thousands of dementia patients in clinical trials. This comes after a historically low rate of participation in clinical trials in 2021-2022, with just 61 patients participating. Although this initiative has been in the making long before NICE’s announcement, it is impossible to not view it as a reaction to the rejection of the two potentially revolutionary drugs.

Earlier in the month, a research team here at Imperial College London received funding from Gates Ventures for a three-year research programme into the risk factors and markers of Alzheimer’s. Headed by Professor Lefkos Middleton at the AGE research unit in the School of Public Health, the programme will explore the cognitive trajectories of individuals with differing levels of beta-amyloid (the protein targeted by donanemab) and tau. It will act as a continuation of the CHARIOT PRO sub-study, which is among the largest and most comprehensive studies to explore the changes in cognitive health in older adults over time. Thanks to the funds, the follow-up will expand to 12 years.

Although NICE’s decision to reject the provision of donanedab and lecanemab on the NHS is undoubtedly disappointing to both researchers of Alzheimer’s and those affected by the condition, these two new developments disprove the idea that the UK is not a hub for innovative research into Alzheimer’s.