Nostalgic music

Does the music of my teenage years actually sound good? Was my taste just trash?

It’s a question that arose, oddly enough, due to an online pub quiz my flatmates participated in - specifically, the task was to listen to old drum-’n’-bass mashups and write down the titles of the original songs. After suffering through a painful butchering of Slipknot’s anthemic ‘Duality’ - reminding me more of a nightcore rendition passed through some vice-grip compression than a DnB classic - I set off on a nostalgic journey through some of the 2010s music of my teenage years.

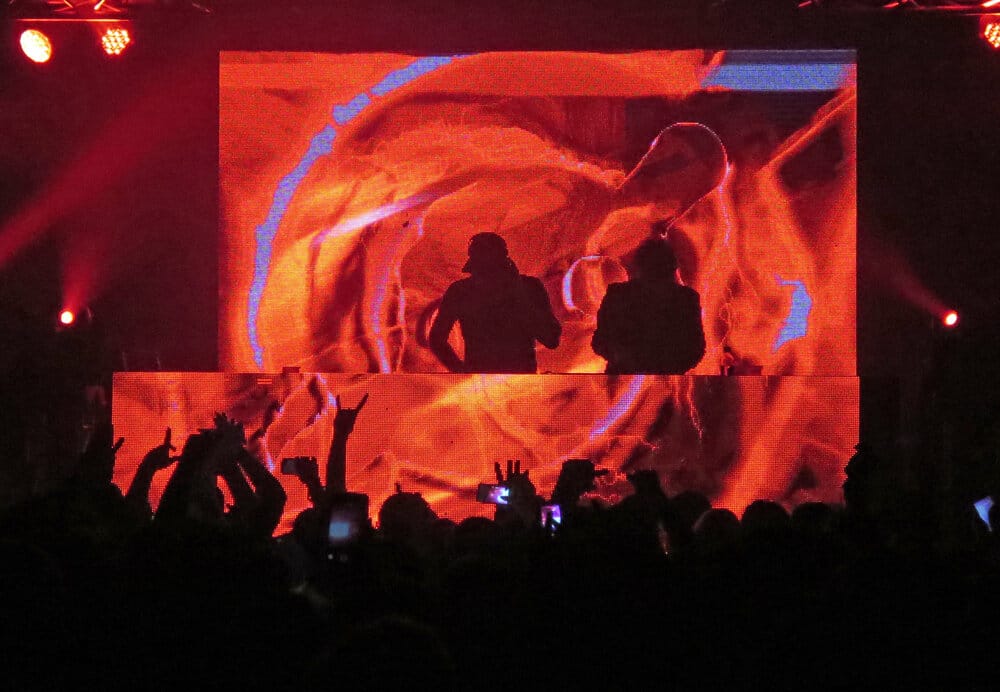

Listening to the not-so-dulcet tones of Skrillex, Klaypex, Nero, and Knife Party, I found myself asking: does this actually sound good?

Dubstep was an arguably controversial genre when it arose. Thicker than marmite, with tracks packed with those iconic warbling rhythmically-manipulated bass notes and relentless tempo, it had that same ‘love it or hate it’ quality. Much of the popularity of dubstep was arguably driven less by the music and more by the surrounding cultural battle.

Modern electronic music was facing an identity crisis: did electronic producers want to pursue the approval and pedigree of traditional music production, demonstrating the artistry of their work through intricate imitation and call-backs to older music, or did they want to go their own way and prove their worth through wild innovation?

Dubstep, I’d argue, reflected the latter desire. It typically alienated older audiences who likened it to “just noise”, and drew the young like moths to a flame, high on the sense that this music was their own - that this music was revolutionary, setting itself apart from what had come before and challenging musical preconceptions. It’s debatable whether this was really achieved - in the end, much of what made dubstep “unique” to the uninformed did end up being borrowed from earlier genres - but what mattered more than this truth was the cultural perception. A lot of people liked dubstep for what it represented, more than for its musical quality.

Listening to those classic tracks now, removed from that cultural discussion - after all, the genre has been around long enough to become giga-mainstream and then to die out - I realised I couldn’t tell whether it sounded good or not. For the life of me, I didn’t know whether it was sonically pleasing, as I thought it was a decade ago, or “just noise”.

This is both the problem with and the benefit of nostalgic music. Those songs just drag up an array of thoughts, emotions, and feelings - it may remind you of a specific memory or person, or just elicit a vague sense of a time or place in your life. Beautiful music can be ruined by the fact it was the song you and your ex used to listen to.

The vice versa applies, too. I will forever associate Nickelback not with being awful (as I should), but with blasting down the blessedly-empty M6 toll road at definitely-not-above-the-speed-limit with my family, on a long drive between my home in Edinburgh and that of my Gran and Auntie in Berkshire. Yes, this is my confession: I listen to Nickelback and my ears don’t immediately look for a bridge to yeet themselves off of.

In the end, listening to music is an experience. Maybe I’m just trying to justify my trash taste here, and I feel like a traitor to musical purists everywhere, but I’m forced to conclude that that experience exists way outside of just how artistically pleasing the sound waves are. Nostalgia, or indeed associated cultural perceptions, or a hundred other things can make a song sound great or terrible to your ears. That’s why I can’t tell if it sounds good, or not - the experience supersedes everything.

It never mattered whether dubstep was good or not. It matters what I feel when I listen to it - so off I go to listen to more Datsik, and fondly remember that party where I drank far too much rum at Halloween while dressed as Jack Sparrow.