Passive and Active Investing – A War that Never Ends

Buffet’s infamous bet would seem to show that ‘dumb’ passive investing is the way to go - we discuss why it isn’t so clear-cut!

The first day of 2018 brought to an end one of the most notable open disputes in the investment industry – precisely ten years prior, Warren Buffet offered a $1M bet to any hedge fund that would be able to outperform a ‘dumb’ passive index, the S&P500. This bet was taken by Protégé Partners LLC, and surprisingly (or not), Buffet won. How did it happen that a ‘dumb’ fund index turned out to be ‘smarter’ than the selective investments of prestigious hedge funds? Is there any theoretical explanation behind this phenomenon? Why do investors use professional investment managers then? These are just some of the questions that this article aims to answer.

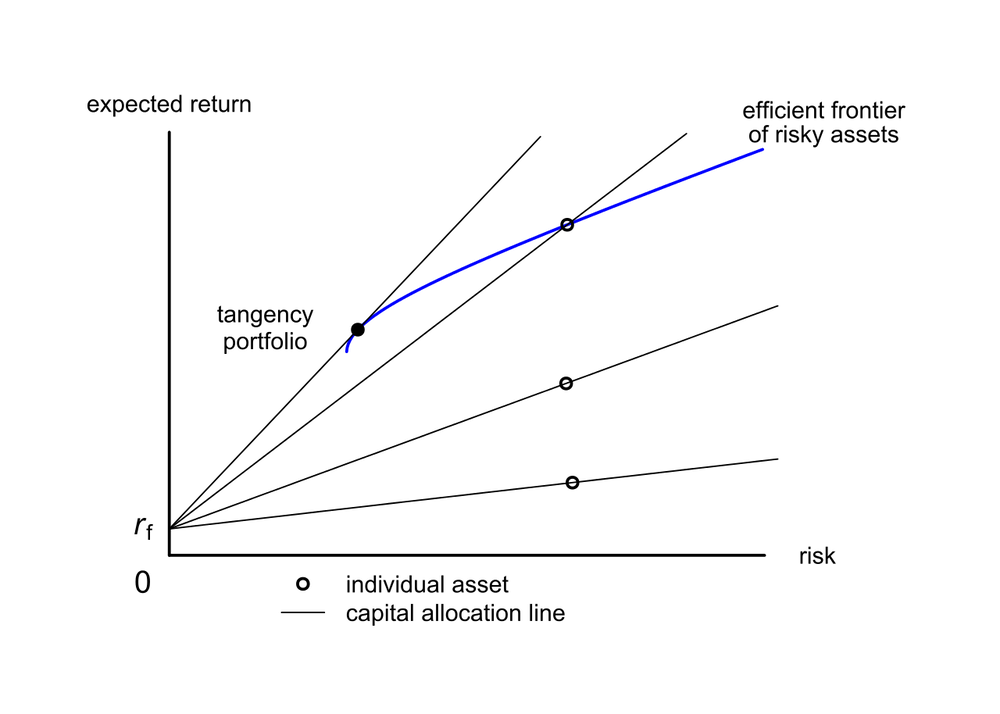

First, let us jump into theory. In 1953, the breakthrough paper named ‘Portfolio selection’, written by Harry Markovitz, came out. Markovitz analysed several different portfolios that varied by risk (measured as standard deviation) and expected return. There were two key findings in this paper. Firstly, it was statistically illustrated that the only way to increase your overall expected returns is to take on more risk. Put it simply: if you prefer that your portfolio grows faster - pick riskier assets. This is illustrated by the graph in Figure 1. Secondly, after evaluating reward/risk ratio* for each portfolio, Markovitz arrived at a conclusion that, based on this parameter, the most optimal portfolio to choose is the one which covers the entire market. In other words, if you want to have a portfolio with a maximum return/risk ratio: buy the whole market (or at least, get as close as you can). This fundamental principle is otherwise known as diversification.

Although the doctrine of diversification has been long known by humankind, it has not been that widely applied for equity and bond purchases amongst the public. The reason behind this is plain simple – it was quite costly and tedious for an average investor to buy a large quantity of broadly diversified assets. The solution came in 1976 with the creation of index funds by John Clifton, the chief executive of the Vanguard Group. However, it was not until the 1990s that ETFs (Exchange Traded Funds – the most popular form of index funds) gained their popularity, opening a whole new market for passive investing.

The principle behind this is simple – an asset manager purchases a large basket of assets (like stocks). It then sells tiny parts of this newly created fund to investors in exchange for a small percentage fee (usually <0.4% of net asset value). In the case of passive funds, the portfolio is not actively managed by the fund throughout its operation – all the assets are picked at the start and are rarely varied since then. Those assets are usually chosen based on a certain criterion - one can find index funds of oil & gas companies, stocks of emerging markets, American bonds of various maturities and many more. One of the most popular ETFs of all time, for example, is the so-called ‘Spider’ – an index that tracks the Standard & Poor's 500 index (S&P500). The price of these funds is directly linked to prices of its underlying assets.

Up until now everything has been in favor of passive investing – index funds provide the best value-for-money (defined in terms of risk/reward ratio), undertake the dull process of monitoring the index for themselves, and charge a minimum fee for doing all this. Is passive investing a haven for investors? No; it is not that straightforward.

Modern Portfolio Theory, like any other theory, is built upon certain assumptions. Although there are several (and all are quite ‘idealistic’), let us consider just one – that investors are always rational in their evaluation of available information. This implies that all assets are always accurately valued according to all the information available on them. However, our own experiences can tell us that this is far from reality. Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman† have shown human’s irrationality through a series of experiments. Therefore, assets are not always valued accurately – there are ‘flaws in the system’. Here is where active investing steps in.

The aim of active investing is to find and buy undervalued assets on the market, thus outperforming the benchmark indexes such as the S&P500 for American equities in the long run**. Let us investigate active investing from the point of view of an individual investor. They have two options:

1. Search for such assets by themselves

2. Delegate this to professional asset managers by investing into one of their funds

The main reason why option (1) rarely works is because an individual investor is always competing with all other investors – thus, to outperform, they should be better than most market players. Simply being ‘smarter’ than hedge funds, investment managers, and other titans of industry such as Warren Buffet is easier said than done. Thus, option (2) is generally more reliable for an individual investor.

The main difference between actively managed investment funds compared to their passive counterparts is that the assets in their portfolio vary depending on the market situation. Active funds also come with heftier fees, although fund managers promise to outrun them using their investing strategies. On average, these fees are 1-2% of assets-under-management, which can amount to eye-watering sums for large investors.

There is also a common misbelief that beating the market in the long run is impossible, and all actively managed funds return to market-average returns in the end. Several fund managers have broken this myth – one famous example is Peter Lynch, who helmed Fidelity Magellan and achieved a 29% average annual return for 13 years.ˆ

The choice between active and passive investing always remains opened and depends on the investor’s aims, expertise, and time available for evaluating investment opportunities. There is no unique formula that applies to everyone. However, observations show that index funds are more popular during long bull markets (when everything is rapidly growing) and actively managed funds are trendier in more difficult times. The recent bear market, caused by Covid-19, is an excellent opportunity for active investing to prove its worth once again.

\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_\_

*An interested reader could do some more research on Sharpe and Sortino ratios_

†Kahneman and Tversky were among the first ones to statistically prove that humans do not think rationally

†The founding fathers of behaviour finance

**Though the goal of some funds could also be to maintain a certain return ratio despite market conditions

ˆWhich does not mean that he will repeat this performance for the foreseeable future, although 10+ years is already a long enough horizon to draw conclusions