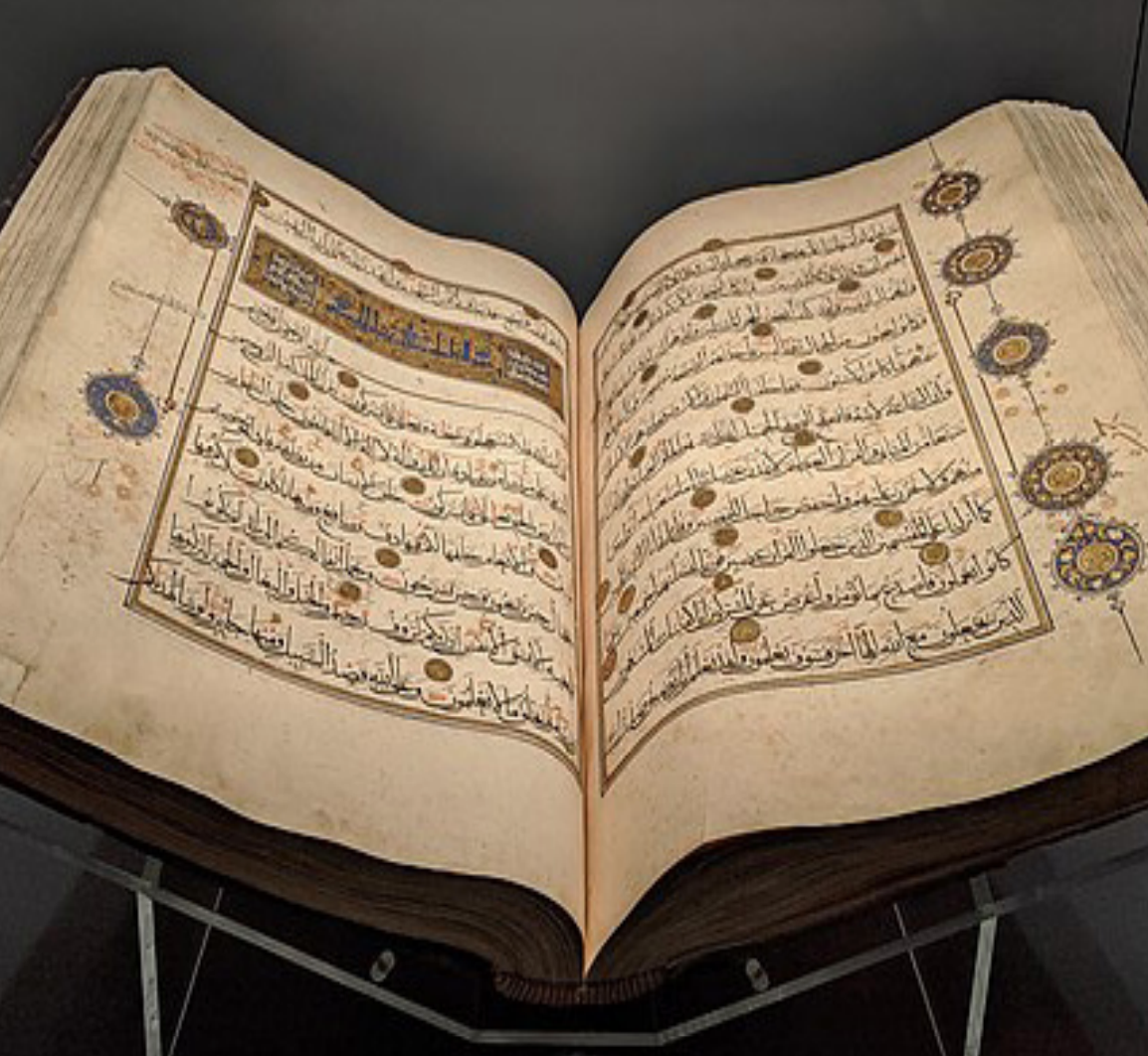

Project Illumine — a Qur’an commentary for our time

Steve Connolly urges readers to look at the Qur’an with a fresh pair of eyes

Ironically, like science, people get out of the Qur’an what they project onto it. Avoiding confirmation bias requires the true enquirer to engage dispassionately, neutrally, and with dedication to discern the multi-layered meaning according to its own terms. Without suitable guidance however, even the most well-intentioned approach is likely to fall foul to misunderstandings, assumptions, idiomatic expressions, and decontextualisation, as well as naïvely simplistic literalism anticipating the spectre of legalism. Compounding these, the projection of egotistical biases and prejudices leads inevitably to cherry-picking, resulting in a message that is incondite, confusing, and antiquated — hideous darkness masquerading as enlightenment; the prize for the unwary.

The genius of the Qur’an partly lies in its ability to address people in every age post-revelation. To its pre-modern recipients, passages like (51:47) “We built the universe with great might, and We are certainly expanding it,” and (21:30) “...the heavens and the earth were one mass, and We tore them apart[...],” were clearly inexplicable, but to people familiar with Edwin Hubble’s work these now make perfect sense. Conversely, the original meaning, understood within its 7th century context, relating to much of its content, only resonates superficially, as our intimacy with its initial setting has diminished over time. The once familiar have become unfamiliar, aggravated by the accretion of dogmas, embellishments, and common mythologies — memes, if you like — aided by intellectual indolence, factionalism, and bouts of ideologically-driven campaigns to frustrate the message under the aegis of imperialism, both ‘Islamic’ and European.

Originating a fresh and innovative understanding of the Qur’an, the polymath Khaled Abou el Fadl (abul fadl) is close to completing its first direct-to-English commentary (tafsir) in 40 years via YouTube (Project Illumine, The Usuli Institute), with future publication in the offing. To demystify the text, Abou el Fadl employs the revelation’s axiomatic moral and ethical propriety to guide his own holistic, thematic, and contextual analysis rather than getting bogged down in the traditional, all-too-often navel gazing, line-by-line treatment. As might be expected of a scholar, there is the requisite literature review — extensively referencing the ~1,000-year-old tafsir genre — complemented with novel research where applicable. The result is transformational.

THERE IS NO LONGER ANY EXCUSE TO CONTINUE MISCITING THE QUR’AN

Take, for example, the allusion to judgement day in the chapter The Moon (54:1) “The hour has drawn near, the moon has split,” which precludes a literalist interpretation; exemplifying the Qur’an’s use of the past tense to reference the future; differentiating Divine from human time. The absence of reliable eye-witness testimony discounts this assertion in the narrative literature, indicating folkloric embellishment of a prophetic miracle, or the common and pervasive mythology that stoning to death is an Islamic prescription despite contradicting the Qur’an. Instead, because of the infeasibility of providing four eyewitnesses (24:4), the entirely notional penalty for adultery of 100 lashes, according to the chapter The Light (24:2), emphasises the egregiousness of the sin. As Abou el Fadl points out, however, the real focus here is on deterring slander (penalised with 80 lashes), the Prophet’s wife famously suffering this accusation. Literalistic and legalistic prescriptions aside, recourse to a fine would likely constitute a just, modern Islamic punishment for defamation, mirroring the remedy available under English law. As for the adulterers themselves, societal approbation and civil-law-like rather than criminal (hudud) proceedings would presumably suffice today.

What about the notorious wife-beating verse? Chapter The Women relates the tradition of husbands accusing their wives of sexual impropriety (nushuz) — based on the suspicion (real or otherwise) of their spouse taking a lover while he was away on extended travel — leading to her indefinite incarceration in the family home (or worse), thereby facilitating his remarriage. The passage concerned (4:34) is revolutionary because it abolished the husband’s culturally assumed prerogative to unjustly accuse and unilaterally punish his wife, instituting an alternative public judicial process with a range of options instead. Misconstruing this, patriarchally-inclined jurists subsequently invented, as the professor notes, the legalistic fiction of the husband lightly beating his disobedient wife with a toothbrush (miswak) to maintain familial order even though it apparently contradicts the next verse (4:35) where arbitration to resolve their differences is recommended. Abou el Fadl’s Project Illumine covers a plethora of such examples demonstrating the inappropriateness of much of the received Qur’an commentary to date. His work is an indication of the qualitatively superior textual understanding now available which relates to people living today rather than reflecting ye olde world of yesteryear. Consequently, there is no longer any excuse to continue misciting the Qur’an owing to suitable and accessible information.