The Magic Flute Entrances, But Does not Enchant

Royal Opera House strikes again with a classic Oldie!

Magic Flute

★★★

- What: Opera

- Where: Royal Opera House

- When: Until 7th October (Streams until 30th October)

- Cost: £25

Watching opera is itself an act of theatre. In the trivial sense, we audience have our costume and our lines, our exits and our entrances, but - for those as jejune as I am - the stage upon which this second performance must be played is nine-tenths internal. Observation is regularly self-reflexive, but the cultural esteem in which opera is held raises this to the level of a pathology; one questions one’s own experiencing of the show in the midst of experiencing it - “am I watching correctly?”, “am I listening correctly?” and, above all, “am I understanding this?”

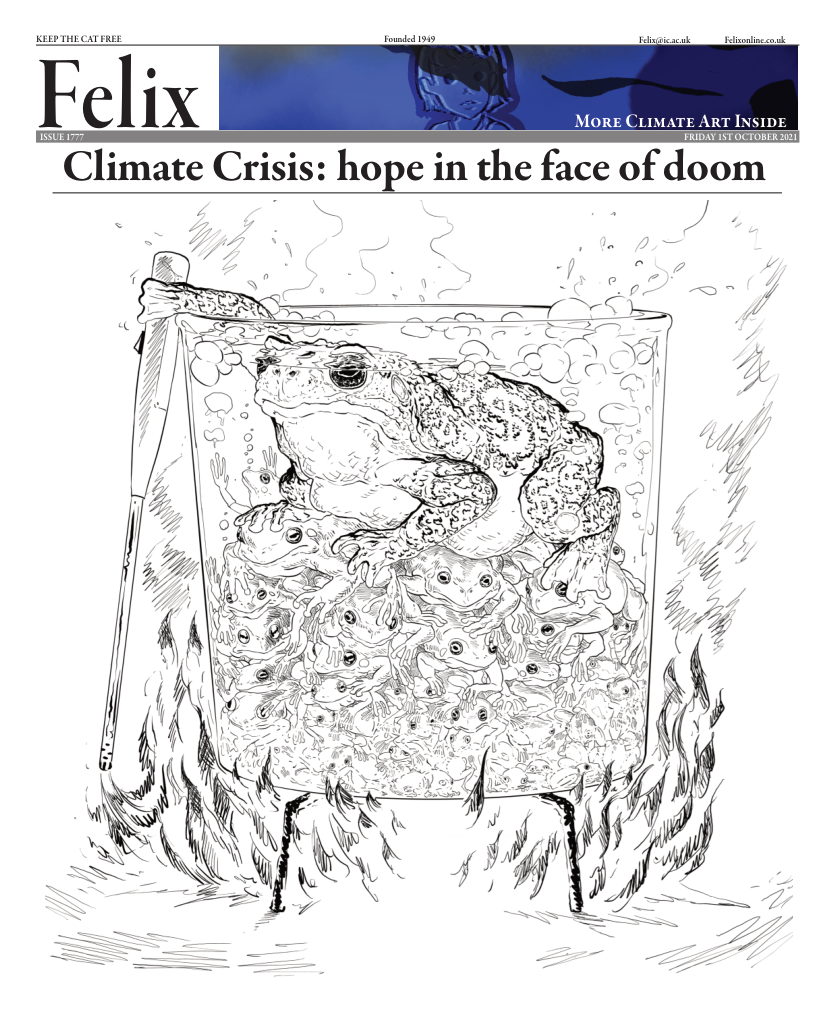

For the most part, these are the wrong questions: the Royal Opera House’s production of the Magic Flute is entirely immediate. The plot, where it exists, is simple: the prince Tamino (Daniel Behle) must rescue the Queen of Night’s daughter from her kidnapping by the rationalist high-priest Sarastro (James Plott, providing a dirge-like bass), but both find his ideals of sufficient calibre that they choose to bear the trials that will lead to membership in his community and, by extension, their marriage. The bird-catcher Papageno (a tremendously physical Peter Kellner), the rustic id of the opera, accompanies their ordeals and steals all the best lines. This is the 10th revival of McVicar’s production, and its status as an inveterate crowd-pleaser appears unlikely to change; as a warning to the covid cautious, I failed to spot a single vacant seat.

It’s not hard to figure out why. The music is uniformly excellent, with Aleksandra Olczyk’s Queen of Night singling herself out for praise. The sets are of a sufficient scale to impress, albeit rarely sublime (the colour-scape of the night sky is a noticeable miss, though the morning sun, bleeding out in poppy yellow, appears to great effect in the closing scenes - think a defrocked Olafur Eliasson). On the whole, the production is fundamentally light, which aptly suits a libretto so concerned with illumination.

And yet, if light will provide the defining moral - and, thereby, aesthetic - triumph of the singspiel, it will also inevitably cast some uneasy shadows through an audience in darkness. Of course the inevitable sexism is obliquely defanged through the staging, and the production - as is customary - elides any issues Sarastro’s black slaves might bring by simply making them white; it’s the central enlightenment victory instead that sits so awkwardly. The fundamental symbolic regime is of order taming chaos - reason prevailing upon ignorance, music taming wild beasts - but the same world that inevitably drove people into watching this production inevitably comes in too; with an eye on it, the faith in rationalism that characterises the opera appears less optimistic than simply naïve - perhaps more seriously, it fatally neuters the drama of the final trials. But this is all beside the point; you don’t go to the Magic Flute as an intellectual exercise. You can exult reason all you want, but sometimes it’s better to just not think.