Hammer horror & cheesy comedy

The perfect recipe for a Wallace and Gromit film

Around the late 1930s to early 1950s, British cinema took a huge leap forward. The movie production mogul, Michael Balcon had now set firm his position on the top of the Ealing Studios pyramid and, with his position, had brought the films issued forth from Ealing to the front of English cinema. First and foremost, Ealing Studios has become synonymous with the genre of “Ealing Comedy”, a profile into mid-century English comedic practises, laced with laconicisms, double entendres, and some good-old-fashioned plucky English spirit.

Films like Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949), Passport to Pimlico (1949) and The Lavender Hill Mob (1951) set gold-standards for English comedic film practice and issued forth notable proponent actors in the field like Alec Guinneas, Sid James, Kenneth Williams, and Valerie Hobson. These films gave the English audience many stock characters with which to further progress English comedies: the maligned hero, the bumbling parish vicar, the crafty cockney, and the upper-class love interest.

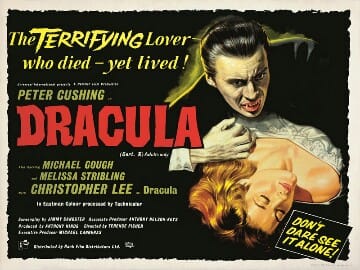

Contrast the capers of Ealing Comedy films from the other side of British cinema, the Hammer Horror film. Hammer Studios, as Ealing was for comedy,

became the focal point for all things gothic in England in the 1950s. While the Germans gave us Nosferatu (1922), Hammer Studios provided us with exceptional renditions of Dracula (1958), Frankenstein (1957-1974), and conjured up the bandaged walking horror in The Mummy (1959). The many familiar faces included Peter Cushing, Christopher Lee and Barabara Shelley.

It seems odd then, to try and fuse these two definitive, yet polar opposite forms of English cinema, but Nick Park at Aardaman always thought otherwise. Having started the Wallace and Gromit series as a pet project in Claymation when he conjured up A Grand Day Out (1989), Nick Park turned to his cinematic instincts and decided to let the inspiration for all the subsequent films pay homage to the various crime-capers and Hammer-screams of the 1950s, all fused with a dash of that quintessential Ealing Comedy. It is little wonder why, despite being set in a fairly ambiguous decade, the Wallace and Gromit franchise feels oddly at home in the 1950s.

When Curse of the Were-Rabbit (2005) came out in cinemas, it was the unveiling of Nick Park’s showstopper piece. It was so much of a showstopper that he managed to beat Hayao Miyazaki for ‘Best Animated Feature’ at the Oscars. But what makes this film truly an endearing classic of British cinema is the fact that it relies so heavily on the features that made English cinema great in the post-war era. Ludicrous characters like the jobsworth police officer, the mad vicar, the posh totty love interest, and the caddish villain all scream “Ealing” to us from the screen. But tinged within not-so-subtle double entendres about a wife’s “ravaged brassicas” and accusations of “arsin’ around”, the unmistakable hint of Hammer Horror seeps in: the perfectly timed thunderclaps, the dark churchyard, and even the concept of an Oliver Reed inspired werecreature of nightmares.

While Ealing and Hammer Studios are now gone, we can’t help but watch them again.

Truly, this film is a perfect pastiche to 1950s English cinema. Yet, it also provides us with the bridge to link the modern styles of animation and British cinema to that of the 1930s-50s, introducing us, as children, to stock traditions in English comedic practices. Most people may often treat black and white films with carefulness, feeling that they really are from a by-gone age of traditions long past; however, if Wallace and Gromit prove anything, it’s that while Ealing and Hammer Studios are now gone, we can’t help but watch them again.