Flesh by David Szalay

A review of the 2025 Booker Prize winner.

Flesh is the story of a single man’s life. From unremarkable boyhood to unremarkable adulthood, it culminates in the formation of an equally unremarkable man. Had I not thought more deeply about the novel through the lens of David Szalay’s craft, I would not have appreciated the deliberateness his style. I didn’t really like Flesh, but I don’t think I was meant to.

I didn’t really like Flesh, but I don’t think I was meant to.

Cohesive but not repetitive and understated but believable, even plotlines that on reflection seem unlikely, become credible through the plainness of delivery. Szalay captures an entire life without dramatising it. Events unfold with an inevitability, and the protagonist István allows them to, taking it neither in stride nor refusal. There is a numbness that emanates from the pages of Flesh, and this emotional flatness rubbed off on me as a reader. Although initially invested, István’s passivity and emotional lifelessness gradually made me feel ambivalent towards him.

The third-person-limited narration reinforced my distance from the novel. Despite being in István’s head, he remains closed off. Saying little, thinking little aloud, Flesh relies on Szalay’s surgical syntax: precise punctuation, implicit subject matter in dialogue, echoes in interactions between characters. The changes in István are subtle but eventually grow palpable; as he grows, the vocabulary describing his surroundings grow, reflecting his age and comprehension of the world.

At times however, Flesh felt laborious. The pacing slowed, perhaps reflecting the differing weight with which we designate stages of life. The tokenistic “interesting” bits, childhood abuse, hardship at war – formative but repressive experiences certainly occur, albeit quickly, and are not addressed since István himself does not reflect on them or consider how they shape him. Perhaps this a mirror to our own ignorance, or perhaps it is Szalay’s suggestion that we sometimes overanalyse ourselves, when in reality our lived experience is a continuum with deep roots too deep to be neatly pulled out and cleaned.

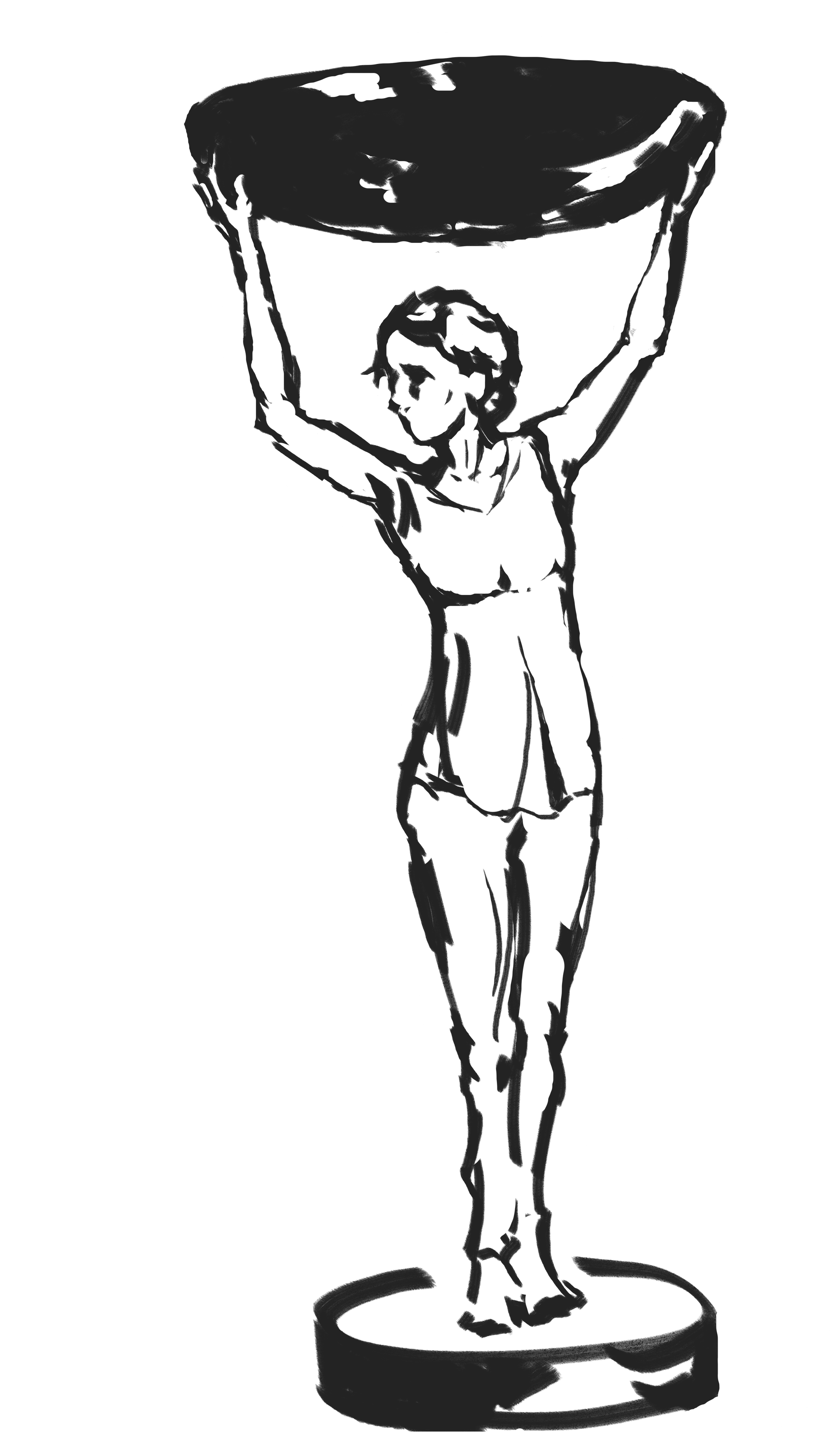

A portrait of a man: naked in his own flesh, carried forward by the passage of time

Other times I felt a disdain for this passivity. I was almost upset with István for acting captive to life’s hardship, as if action was beyond his control – a resignation to aches of the world. But the novel’s cyclical patterns and quiet repetitions create closure in an otherwise deliberately sparse plot. Ultimately, this sheds light on reality. To exist peacefully in the world, one must accept how things are, even if through the form of enduring. And at the end of it all, it is a portrait of a man: naked in his own flesh, carried forward by the passage of time.