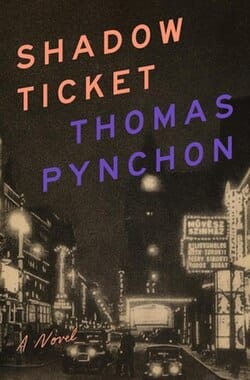

Shadow Ticket by Thomas Pynchon: a review

Thomas Pynchon is fed up. Shadow Ticket, his ninth novel, published more than a decade after Bleeding Edge, is less so a world in which nefarious organisations collide in an ongoing conflict, but more so a world lost. Whilst regarded as a lesser Pynchon, perhaps even in the middle of his oeuvre, it is both a tepid bow out of the culture for the now 88-year-old writer, as well as a “fuck you” to a world losing the war against fascism – a world refusing to grapple with its own history.

Yes, it retains the wacky hijincks, references to wondrous technology, and a myriad of zany names and pastiche songs thrown into its short 293 pages. But the central thesis of the novel is the failure of Americans, and with American monoculture dominating globally, to assess their role in history. It’s an author giving up and saying, look, the chuds have won.

(Chud: derogatory insult for (usually a man) on the far right, typically of little material means or social capital. Think Twitter right-wing troll, or someone who would join ICE.)

Take protagonist Hicks McTaggart: former strike-breaker turned private eye, set on a merry romp across Europe, not by his own design. McTaggart’s unwillingness to accept his role as a strike-breaker leads to the material conditions that encapsulate America at the novel’s (rushed) climax. There is no satisfying payoff. Pynchon leaves the novel as an open end in this alternate history, with no certainty for McTaggart, who’s left stranded in Europe on the precipice of the rise of the Nazi Party, alone with a woman he seems to be unconvincingly in love with, after his real love interest marries a mobster.

The first half of the novel is Hicks getting his just desserts, as his past all collides into a locomotive of bullshit that is about to hit him. It seems obvious to everyone that the writing is on the wall but Hicks, in his chuddishness, fails to realise that. He is a perfect mirror of the new American right, the new Anglophone right, lamenting a childhood he doesn’t wish to escape from, completing immoral jobs purely for personal gain without any thought of the social impact his individual actions can have; being the “gorilla” without having to grow up, even if growing up and leaving is the right thing to do. He views his history as a set of random points, not a continuous narrative webbed by the decisions he has made, a point expressed very concisely by the character Dudley Eigenvalue in V, Pynchon’s debut.

America has done the exact same: every event occurring, every demagogue populist, the state of the countries’ body politic is somehow random to every pundit, wonk, and professional; but it’s all adding up, and coming to roost. Hicks longing for a “country not yet gone Fascist”, despite literally visiting a Nazi bowling alley with his uncle, is exactly the sort of sleepiness occurring in America right now. Disagree all you want, but there are abductions of people on the street via ICE, homes torn apart. Our very own British government wants to take jewellery and valuables off of refugees. What prescience novels like Inherent Vice and Gravity’s Rainbow had doesn’t matter anymore. Reality turns Pynchonian. We are all Charlie Kirk.

And that is why the novel is itself a myriad of untied knots, loose ends drifting in the wind as the final pages unravel. It’s open-ended because the lesson isn’t learnt. It is a fitting final piece for a man whose career spans the oppressiveness of genre, language, and more, and it channels its old man energy into a final desultory body.

Goodbye Mr Pynchon, we thank you for the work. We laughed too hard to see what you warned us of all along.