Watson is gone. It’s time to remember Rosalind Franklin.

As tributes pour in for James Watson, science must reckon with the woman his legacy eclipsed.

James Watson’s death this week has sparked tributes to a “pioneer of genetics.” Much of the world is remembering him for his work uncovering the double helical structure of DNA – a dignity in death not afforded to Rosalind Franklin, the scientist whose work made that discovery possible. While Watson’s name is etched into the annals of molecular biology, Franklin’s remains eclipsed and hidden.

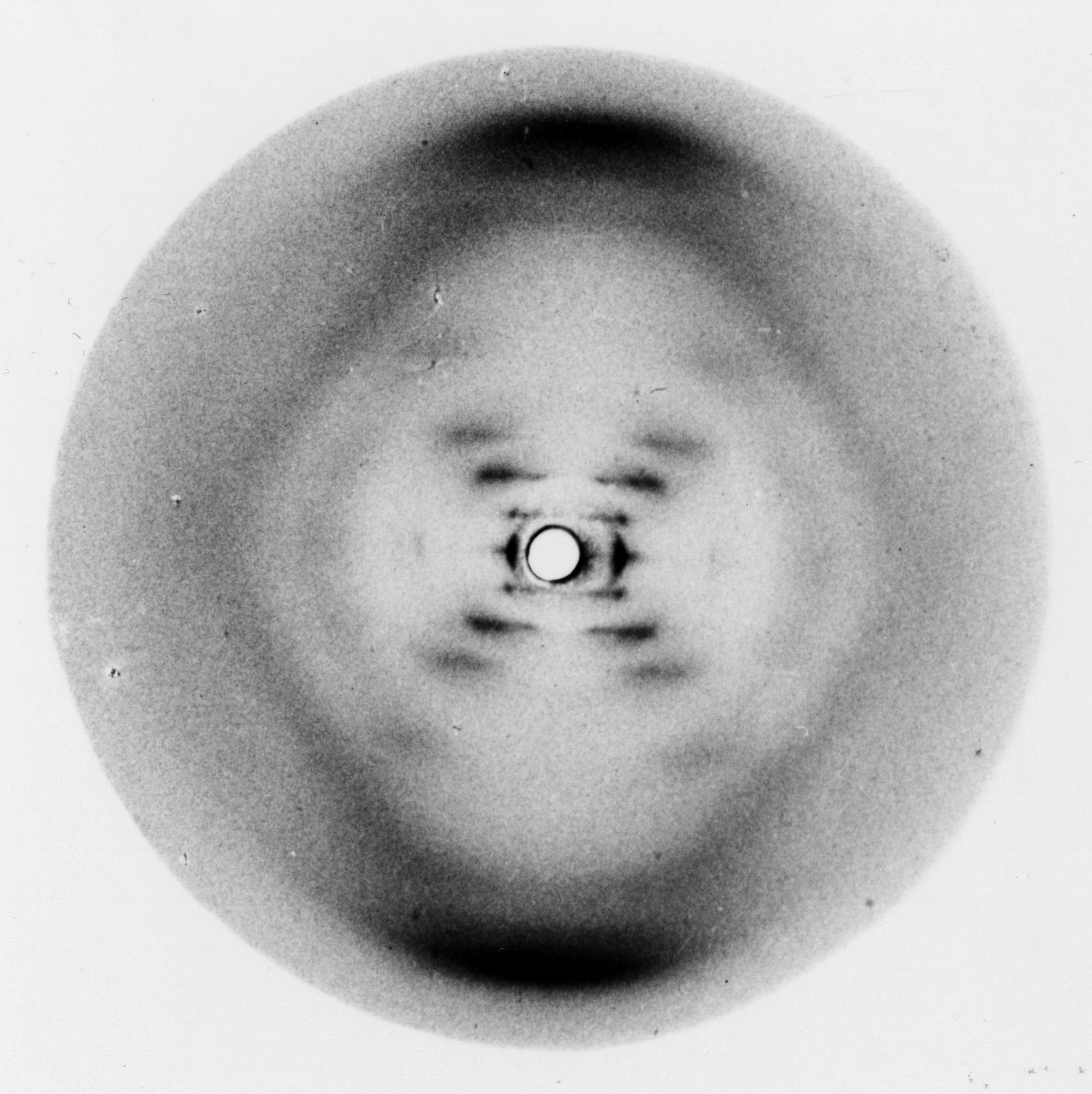

It was Franklin who produced the first clear X-ray image of DNA’s structure, now known as “Photo 51.” That image, with its ghostly X of diffraction, provided the decisive evidence of a helical molecule, allowing Watson and his colleague, Francis Crick, to build their model of DNA. As a result, in 1962, they shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine alongside a third contributor, Maurice Wilkins.

Decades on, the scientific community has begun restoring Franklin’s name to the narrative it once denied her. Yet this feels like an uneasy act of posthumous conscience rather than justice.

Recent historical research, including a 2023 Nature reappraisal, suggests that Franklin was not merely a data provider but an intellectual equal. She independently arrived at the same helical conclusions through rigorous reasoning, discerning that DNA could adopt multiple conformations and understanding their structural implications. Although information flowed chaotically between Watson and Crick (at Cambridge) and Franklin (at King’s), her data was shown to the former group without her consent. This act is emblematic of how women’s scientific labour was routinely appropriated.

In 1953, alongside the better-known Cambridge paper published by Watson and Crick, two additional reports appeared in Nature: one by Wilkins and one by Franklin. Together, they formed the scaffolding of the discovery, though only the male-authored papers were celebrated. Franklin’s expertise in X-ray crystallography was often undervalued, and her ideas were excluded from the informal male networks that dominated the field.

Franklin was not simply the unwitting victim of theft, as the myth once told, but a collaborator written out of history. Watson’s later memoir, The Double Helix, perpetuated this distortion. In it, Franklin appears not as a colleague but as “Rosy,” a condescending diminutive for a woman portrayed as obstructive and obtuse. Her portrayal in the book is not just patronising; it is historically dishonest and sexist.

While Franklin was undergoing treatment for her cancer diagnosis, she continued to publish and lead research. She died at 37, only four years before her male peers were awarded the Nobel. Whatever posthumous recognition she has since received cannot undo the injustice of her omission. Her inspiring story is a cruel reminder of the many women throughout history whose contributions have been forgotten, the magnitude and impact of which we will never know.