DS26: Alcohol

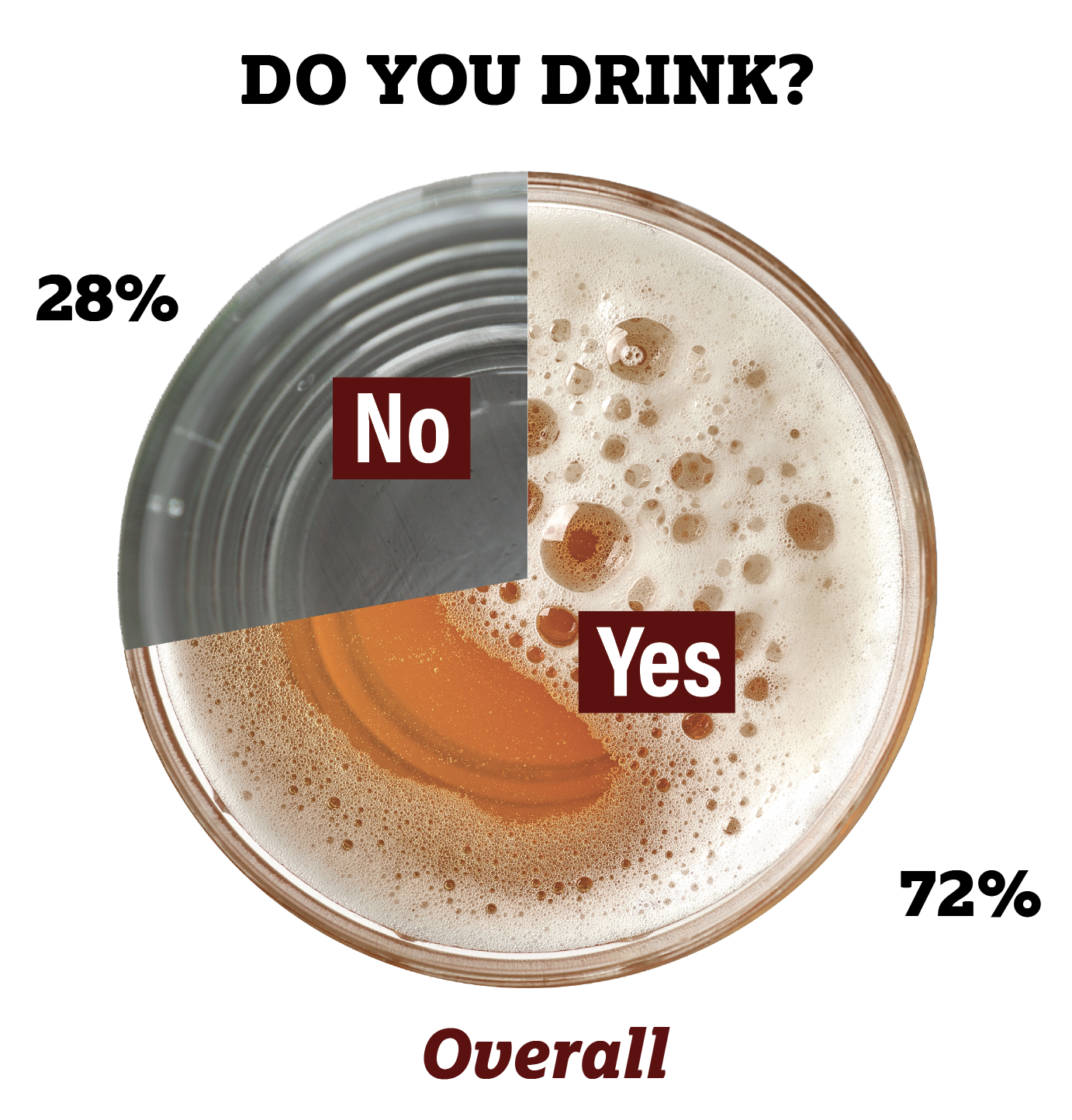

National studies find that around three-quarters of Generation Z drink in the UK, meaning Imperial’s 28% is broadly in line with the average.

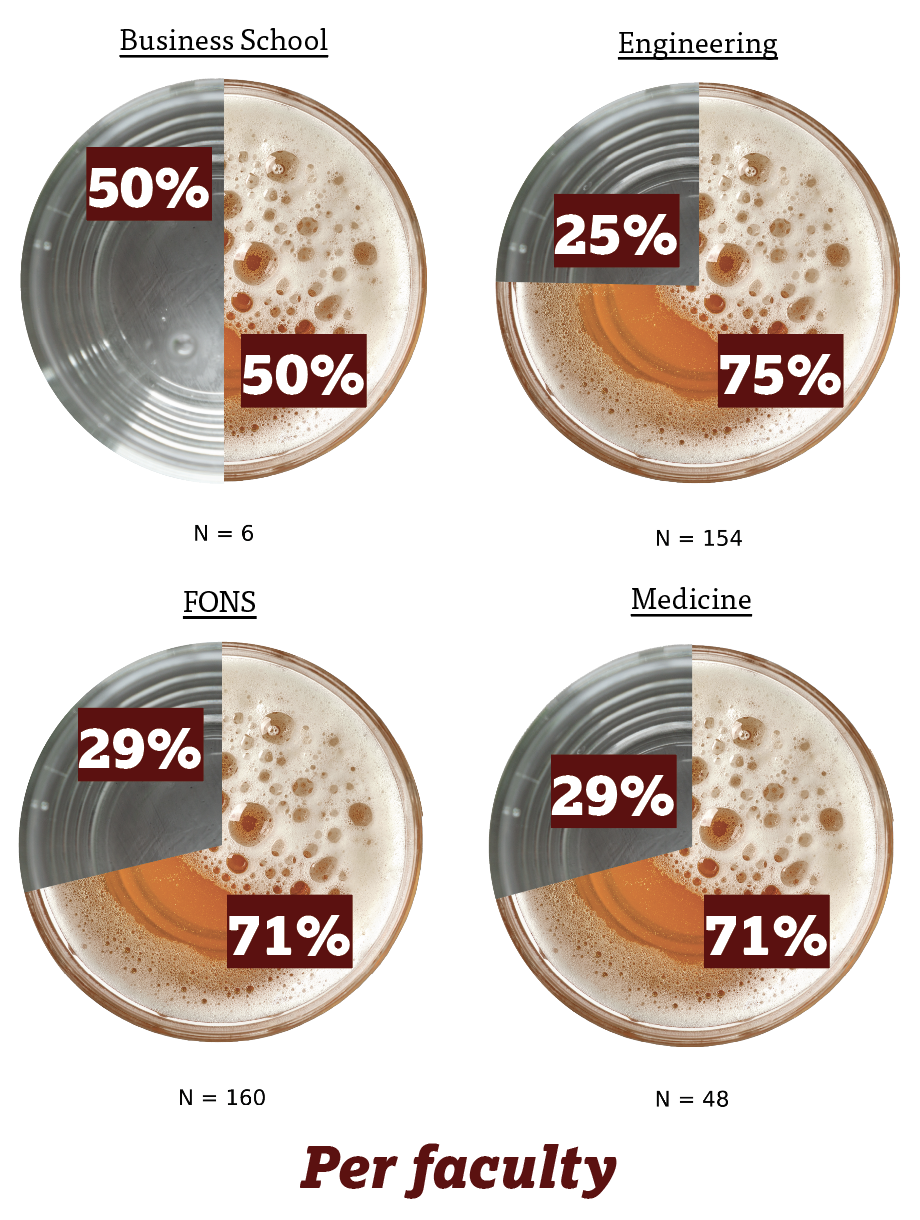

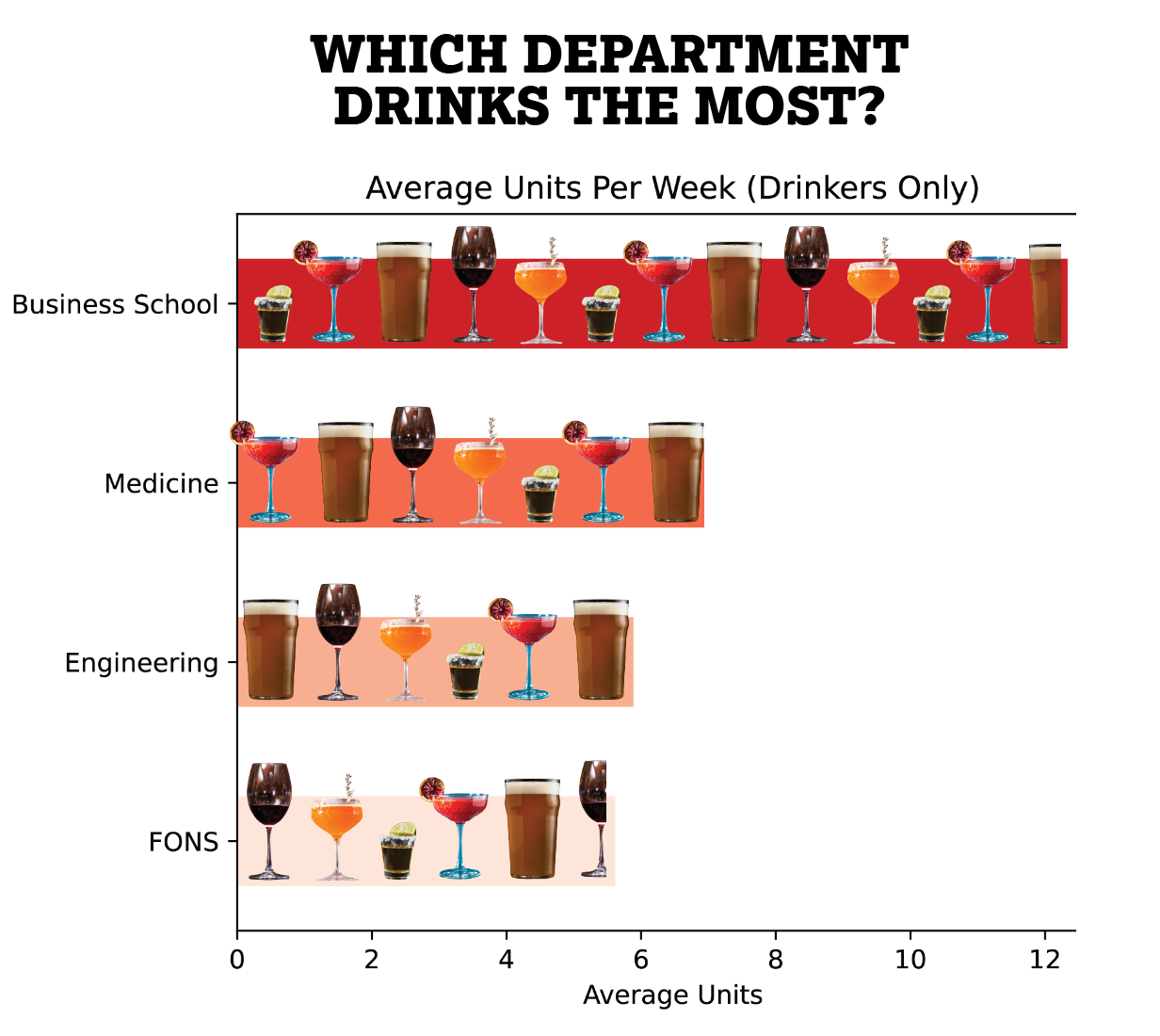

The faculty of engineering had the highest proportion of drinkers. However, among those who drink within faculties, Business School students and medics have the most weekly drinks, although the sample size for Business School respondents is too small to really be meaningful. The good news is that, on average, no faculty’s boozer community exceeds the maximum intake recommended by the NHS, which stands at 14 drinks per week.

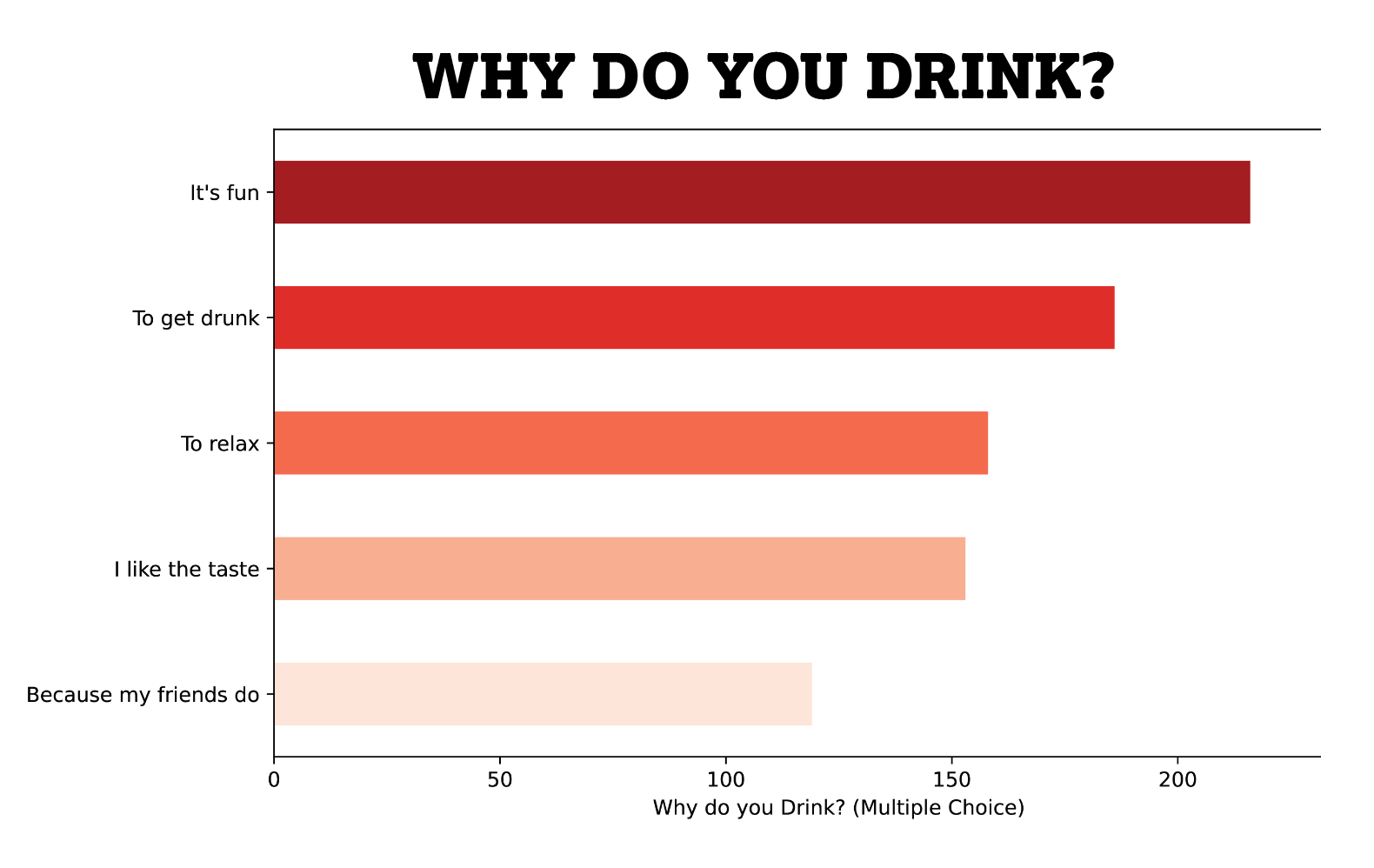

The most common reason given for drinking was “it’s fun”, followed by “to get drunk”. Luckily, peer pressure is a less important factor for students, with “because my friends do” being the least chosen reason for drinking. However, some more concerning free-text answers included “addiction”, “to drown my sorrows”, and “to bare [sic] social interaction”.

We found that the age at which the highest number of respondents first got drunk was 14. This is surprising, and there might be a semantic trick whereby people conflate their first drink with their first time being drunk.

In the UK, it is not illegal to drink alcohol at any age, but giving alcohol to children under 5 or selling it to youths under 18 constitute crimes. The legal age to purchase alcohol doesn’t show in our data – more people had their first binge at 17 than at 18. In England, Scotland and Wales, 16 and 17 year olds can consume beer, wine or cider at a licensed premise when accompanied by an adult. This could explain why more people reported getting drunk at 16 than at 15 or 17.

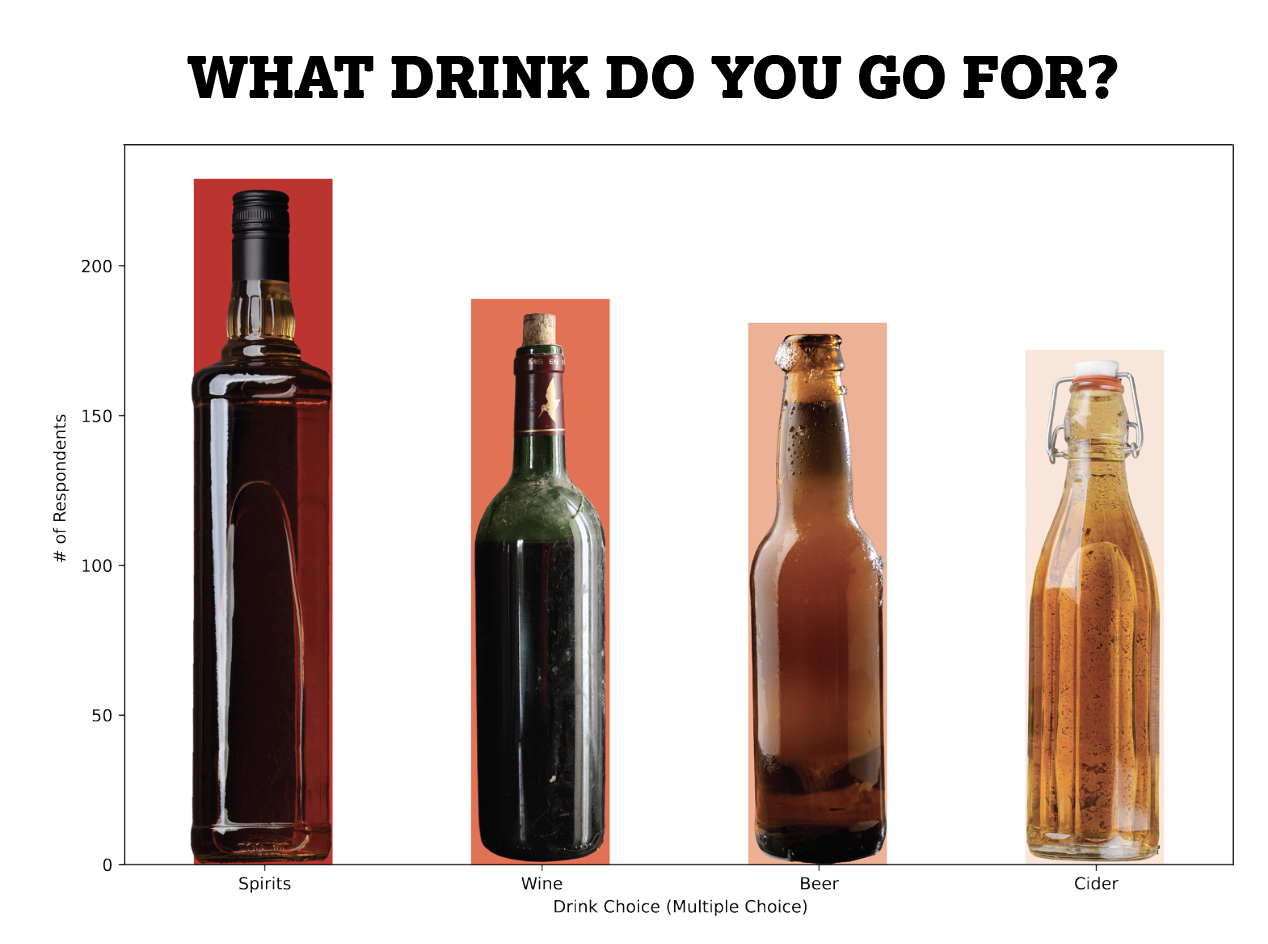

It turns out that students prefer spirits over any other drink, and this is constant among age and faculty. Wine is also a more popular choice than beer, which doesn’t conform to the stereotype of British drinking culture.

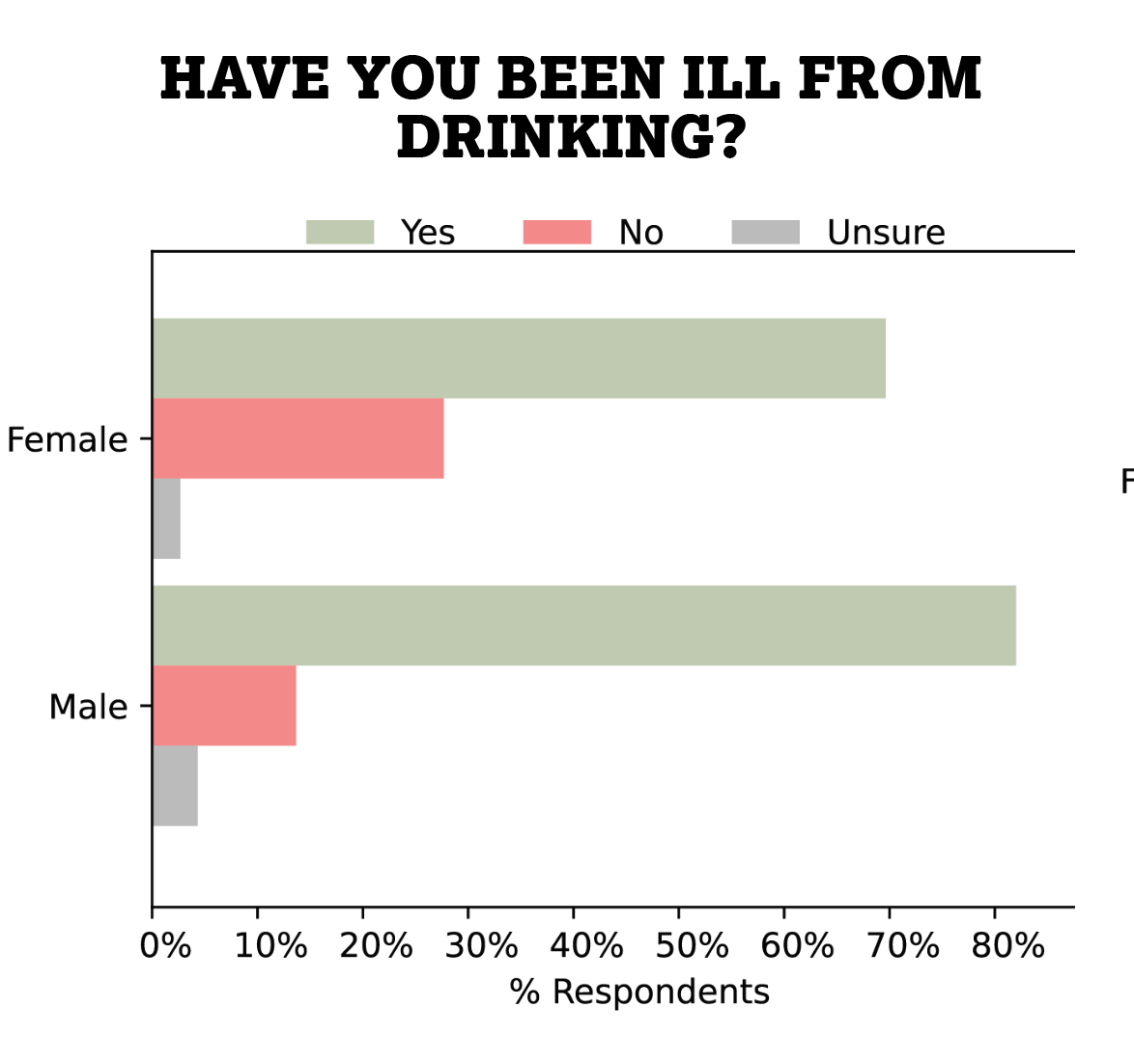

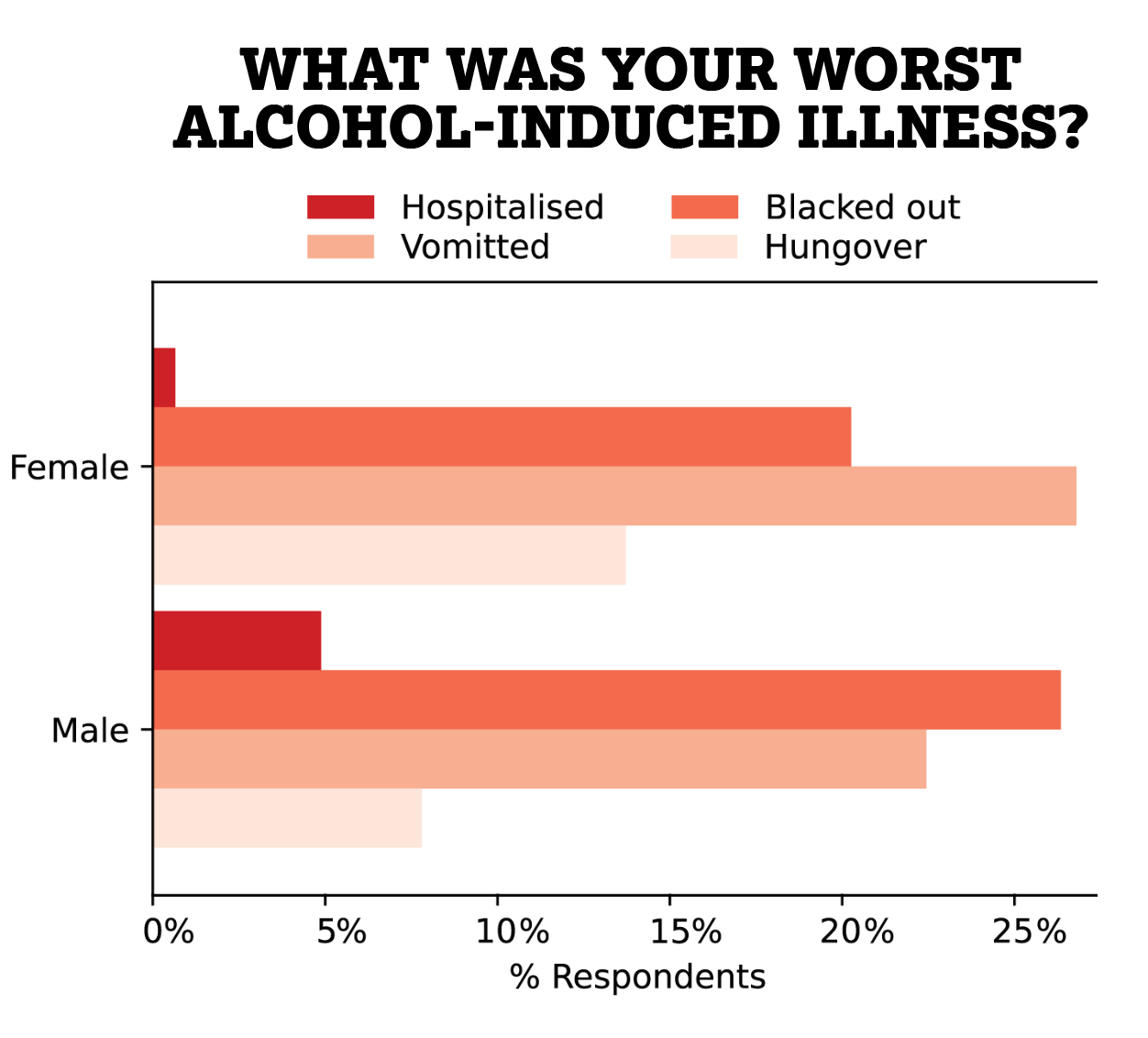

This survey showed that not all of us have the same definition of being ill from drinking. Five respondents said they had never been ill from drinking, but also reported that to have “blacked out” – it should be made clear that blacking out is indeed dangerous.

Females were less likely to have been ill from drinking than males, and those who had reported less serious degrees of illness. (Data from non-binary respondents was excluded because the sample was too small to be significant.) Throwing up was the worst degree of illness that the most women reported, compared to blacking out for men.

According to this data, men were also about five times likelier to had been hospitalised due to excessive drinking. The 5% reported hospitalisation rate in men that have been ill from drinking is also concerning – in that light, it might be good that medics party on the Hammermith campus.