Behind Imperial's Names

What are the stories behind the scientists, statesmen and engineers Imperial is named for?

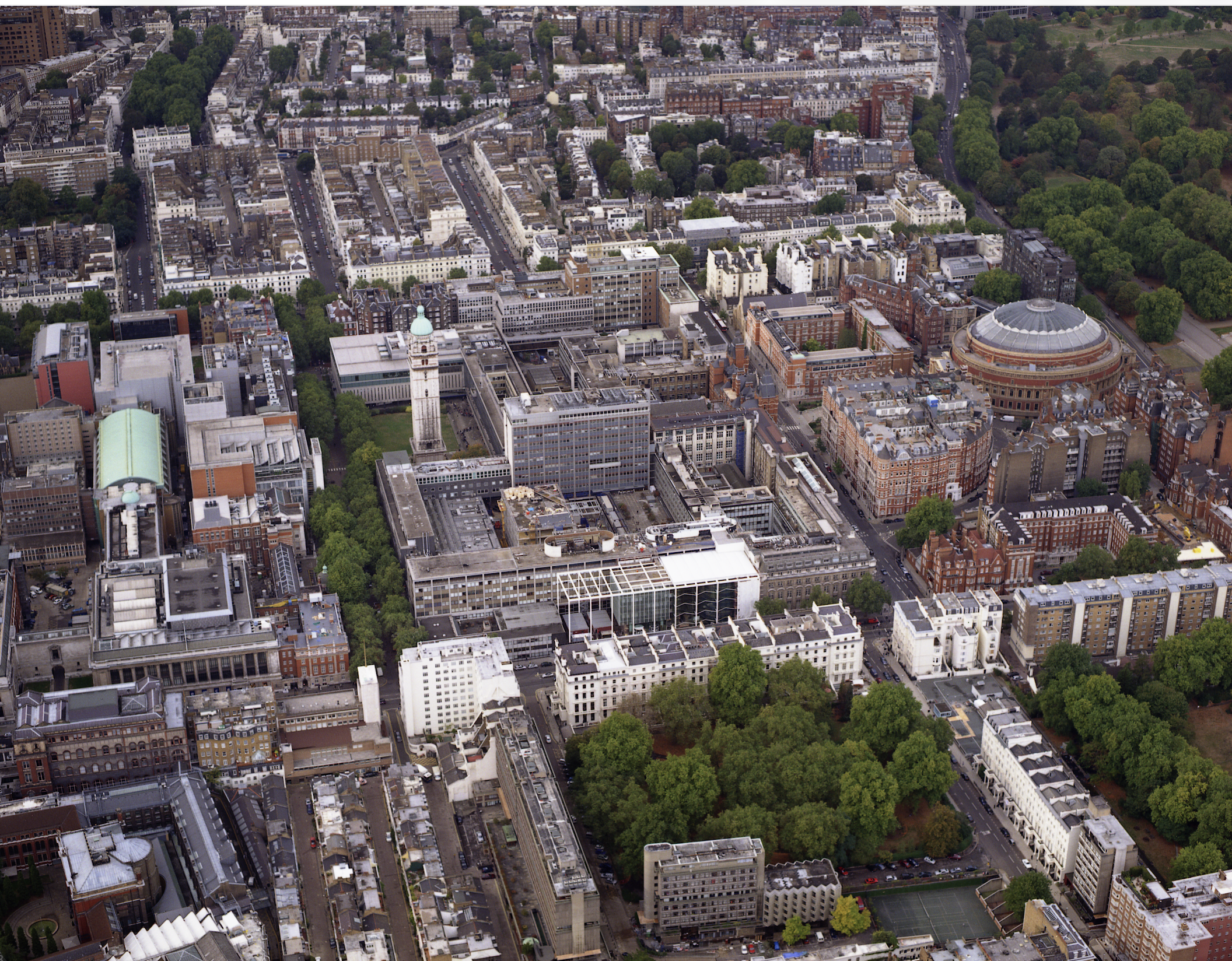

Imperial has many buildings named after a wide variety of individuals. Here we have selected some notable ones on campus (we promise we looked for buildings named after women; apart from halls of residence, there are none). There are of course many institutes and buildings we have not been able to cover, including those not in South Kensington.

Use the toggles to explore the stories behind the buildings you spend your days in!

If you have an Imperial scientist you wanted to see covered, email us! We’d love the article.

Sir Ernst Chain

Sir Ernst Chain was a German-born British biochemist who made the isolation and large-scale production of penicillin possible, sharing the 1945 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. At Imperial, Chain was appointed Chair in 1964, and his passion for biochemistry helped establish the Department, which quickly became an international leader in physiological biochemistry, focused on antibiotic and fermentation research. His strong ties with the pharmaceutical industry pushed the field ahead of its time, and in 2012, his legacy was honoured with the naming of the Sir Ernst Chain Building. Outside science, Chain was an expert pianist and performed with his son.

Sir Henry Bessemer

With over 100 patents to his name, Sir Henry Bessemer was an inventor whose creations served as the backbone of the Industrial Revolution. The Bessemer process, a method of producing steel by blowing air through pig iron, kickstarted the development of buildings and skyscrapers by decreasing the cost and time of production. Aside from the Imperial location, which once fittingly housed metallurgical laboratories, at least eight towns and cities in the U.S. are named in his honour, as well as a mountain in Washington state.

Roderic Hill

Sir Roderic Hill, in a break from tradition with most of the other names around campus, was not renowned for scientific contributions, but rather an illustrious military career. He was awarded the Military Cross during the First World War, after braving heavy fire and diving at a German balloon in his monoplane. After overseeing the Cairo-Baghdad air route and fulfilling various roles in the Air Force, Hill was appointed Commander-in-Chief of Britain’s air defences, and succeeded in mitigating the enemy bombing campaign. He later served as the rector of Imperial College, encouraging students to maintain a well-rounded education consisting of not only science, but also music and art.

James Dyson

Sir James Dyson is widely known as the inventor of the bagless Dyson vacuum. He originally studied art for a year before studying furniture and interior design at the Royal College of Art. His company, Dyson, now also produces hand dryers, air purifiers, hair appliances, and lights. The James Dyson Foundation, founded by Dyson, made a 12-million-pound donation to Imperial to found the Dyson School of Design Engineering.

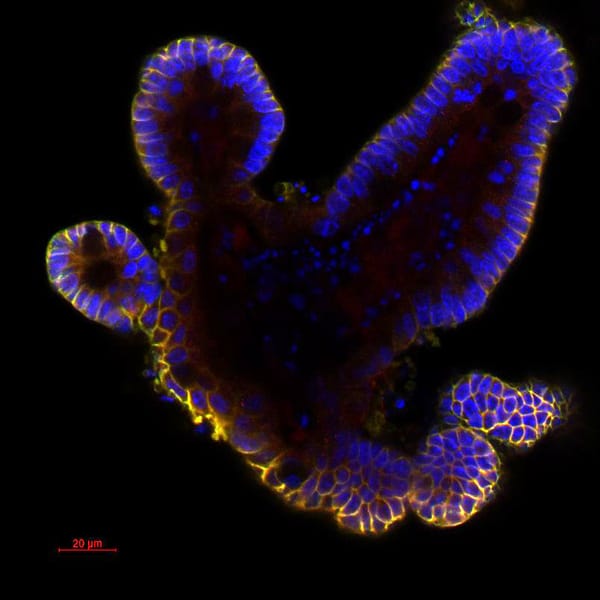

Sir Alexander Fleming

Sir Alexander Fleming was a Scottish physician-scientist who discovered penicillin and shared the 1945 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. His career in research started when the St Mary’s rifle club captain, recognizing his marksman skill, convinced him to pursue a career in research rather than in surgery, as the latter choice would require him to leave the school. In 1928, he noticed that bacteria near mould in a contaminated Petri dish died, leading him to identify and isolate this ‘mould juice’, later known as penicillin. Fleming was knighted in 1944, awarded the Grand Cross of the Order of Alfonso X the Wise in 1948, and recognised by the Time magazine as one of the most influential figures of the 20th century. In 1998, his legacy was honoured with the naming of the Sir Alexander Fleming Building.

Lord Brian Flowers

A pioneer of British atomic physics, Brian Hilton Flowers, later Baron Flowers, was a key shaper of modern policy on nuclear energy. As Rector and then Vice-Chancellor at Imperial, some of his most long-lasting work involved strengthening interdisciplinary connections between departments. He was a founding member of the Social Democratic Party and advocated improvements in environmental policy. An enthusiast of the cello, oil painting, gardening, and computing, he was popular with students, most memorably for supporting them against rising tuition fees, following an ‘open-door’ policy, and hosting twice-a-term ‘beer-and-banger’ parties in his flat.

Thomas Henry Huxley

Thomas Henry Huxley was an English biologist, anthropologist, and coiner of the word ‘agnostic.’ Despite receiving little formal education, he went on to win academic medals at Charing Cross Hospital while on a scholarship. His skill with microscopy allowed him to discover the membrane now known as Huxley’s layer in human hair. Huxley was also a popular science communicator and a strong proponent of Darwin’s then-controversial theory of evolution, a position that has since been vindicated. He fought to make education accessible, writing multiple well-received textbooks and helping bring about the fusion of colleges that created Imperial College London. The History Group, commissioned by the College, found his writings racist in nature and suggested the building be renamed in 2022.

William Ernest Dalby

Most well remembered for his work in balancing engines, William Ernest Dalby was a uniquely determined engineer, researcher, professor, and administrator. He began working in engineering for the Great Eastern Railway in Stratford at 14. Professor Dalby was head of the Department of Engineering for what was then the City & Guilds College between 1906-1913. He wrote a hugely influential book about the balancing of engines and continued to produce research supporting railway infrastructure throughout his life. He was a good administrator, brilliant researcher, and engaging teacher remembered for his practical approach to engineering theory.

Abdus Salam

Abdus Salam was a Theoretical Physicist and Physics Nobel Prize laureate in 1979 for his work on unifying the electromagnetic and weak nuclear forces. He is the first Pakistani, and first Muslim to win the prize. Born in British-colonised India (modern-day Punjab, Pakistan), Salam belonged to a minority community, the Ahmadiyya Muslim community, still persecuted and discriminated against in Pakistan. At Imperial, Professor Salam established the theoretical physics group (now the Abdus Salam Centre for Theoretical Physics). Outside his work, he advocated for accessible science in the Global South, founding the Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics in 1964.